Nest platform may attract a different kind of islander: Ospreys

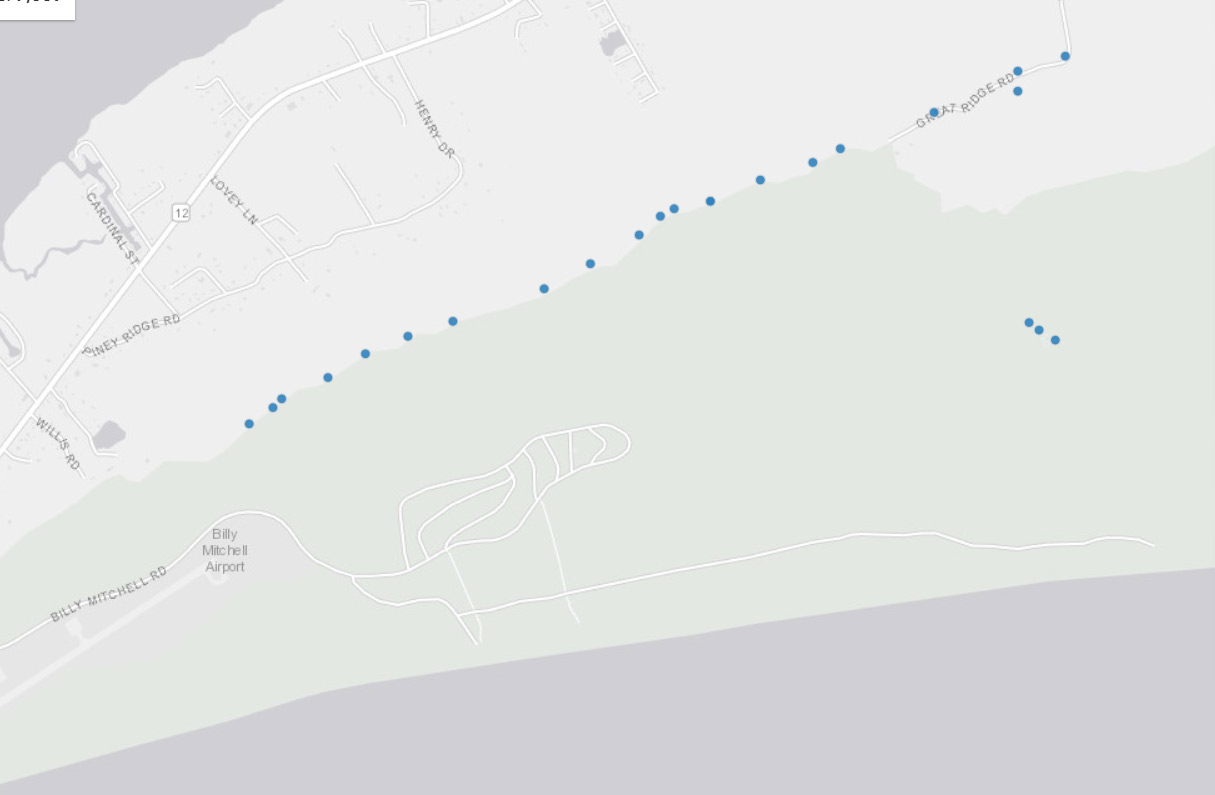

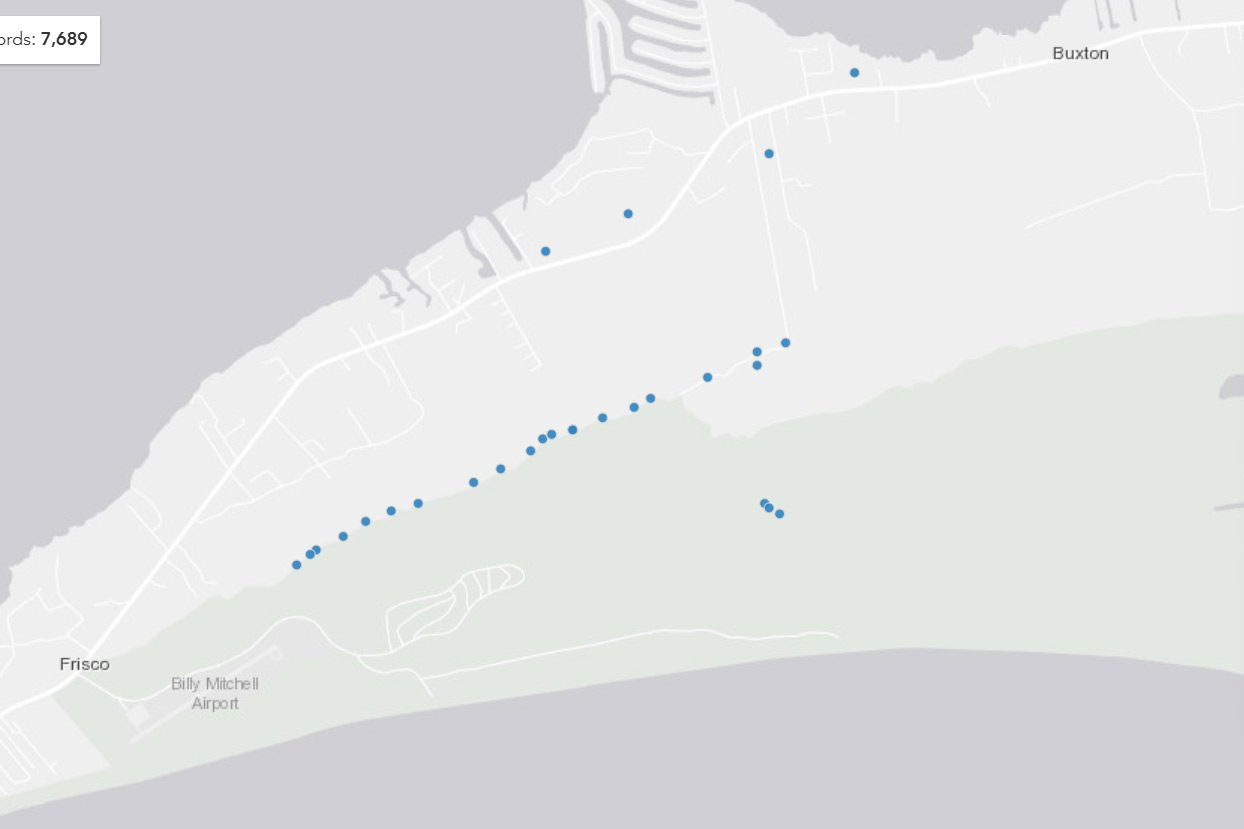

Just off the NCCAT campus in the Pamlico Sound is a new structure.

Though it has a striking appearance, it is not a cell tower or even a modern sculpture. It is an Osprey nest platform.

Islander Heather Johnson, who works at NCCAT (North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching), came up with the idea and got approval to pursue it.

Her fascination with Ospreys goes back a way.

“In my first year working at NCCAT, I watched an osprey land on the nearby rock jetty,” she said. “It was the first time that I was aware of seeing an osprey on the island. I sat there for, like, 20 minutes and just watched it because it was just gorgeous.”

NCCAT Campus Manager Regina Boor was supportive and forwarded the suggestion to Dr. Brock Womble, NCCAT’s executive director, who agreed to the proposal.

“NCCAT is proud be a good community partner in the recent installation of the Osprey nest platform,” he wrote in an email. “It is important to our organization to help whenever we can in Ocracoke community efforts. This project is a great addition and provides a meaningful hands-on learning opportunity as well for North Carolina teachers as we continue the work of supporting teachers while impacting students and families across North Carolina.”

This is a bird with a fascinating life history and ranks near the top for education on many levels.

Ospreys and several other species began experiencing nesting failures when DDT, a synthetic pesticide used to control mosquito populations, was made available for public sale in the United States in 1945.

The dangers of the indiscriminate use of pesticides were brought to light in the 1962 best-seller “Silent Spring,” by Rachel Carson.

For about 15 years, there were no records in North Carolina of successful nesting. A DDT ban was put in place in 1972 and as the chemicals disappeared from the environment, Ospreys and other species, including Brown Pelicans and Peregrine Falcons, began an amazing comeback.

Johnson was so impressed with her sighting because ospreys are large birds of prey, exclusively fish eaters, with wingspans of nearly six feet and body lengths of 24 inches.

Whereas Ospreys historically have selected large trees, rocky cliffs or mammal–free islands to nest, in the last 70 years or so they have used artificial sites for their nests such as channel markers, bridges, tops of utility poles and communications towers.

But the most common sites these days are purpose-built nesting platforms.

Electric utility companies have installed nesting platforms for Ospreys to discourage them from nesting on power line poles.

Ospreys often mate with the same partner for life and begin nesting at age 3. Adults often return each year to nest at the same site where they were born. The large nest, called an eyrie, is made of sticks, reeds, bark, sod, grasses, vines, flotsam and jetsam.

The male delivers the materials, and the female arranges it. Nests grow larger year after year as they “renovate” each spring.

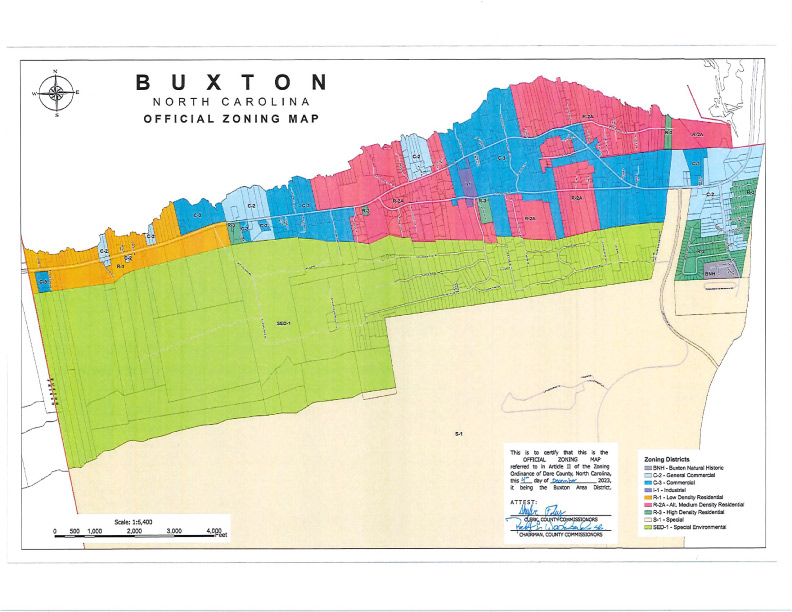

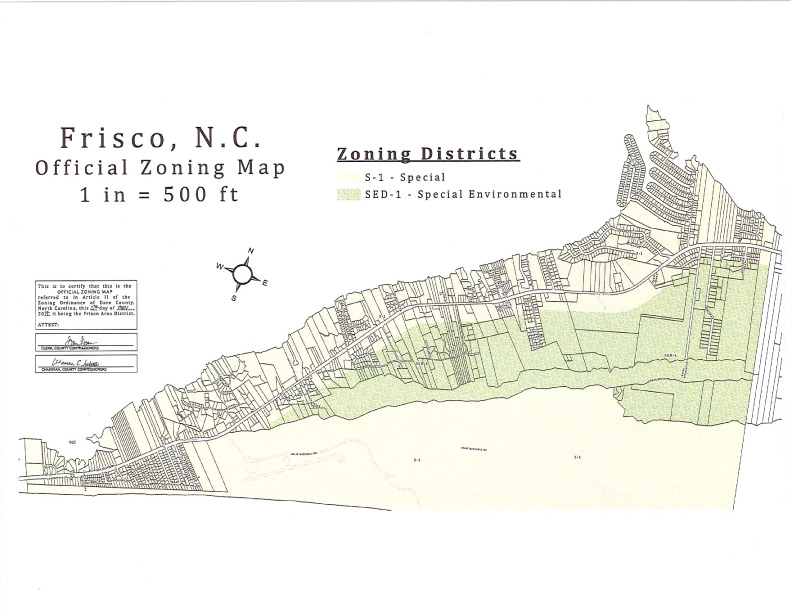

Getting the platform and location approved required the cooperation of NCCAT’s neighbors — the NC Ferry Division and U.S. Coast Guard — and a permit from the Coastal Area Management Act (CAMA) program.

This was a community effort. NCCAT employee Chip Evans built the 4’x’4’ platform, which includes two perches. Darren Burrus, Erik O’Neal and David Scott Esham assembled it to the pole and placed it in the water.

The minimal recommended depth of the pole holes for these platforms is three feet. This one has a depth of 10 feet that will help it withstand the high winds and swirling water surges of major storms.

Flashing, which will serve as a predator guard, will be added to discourage minks that are frequently seen among the rocks of the jetty from attempting to grab eggs or hatchlings.

Johnson, co-author with Ann Ehringhaus of “Ocracoke A.D.,” which chronicles the emotional toll of Hurricane Dorian, is an example of how educational interest in a fascinating species can evolve.

She now photographs and observes birds more closely. Two years ago, she started a Birds of Ocracoke Facebook page that has grown to 1,400 followers and gets several postings of photos daily.

We won’t know until spring whether an osprey couple will build a nest, but in the meantime, it will serve as a safe perch for pelicans, cormorants, gulls and one of the first birds photographed on it, the Belted Kingfisher.

To read more: Birds of Ocracoke: The Osprey