The Peculiarly Harrowing Wreck of the Henry P. Simmons

The Henry P. Simmons was one in a trash heap of ships engulfed in the unholy terror of a great Outer Banks Atlantic rage, known afterwards simply as “The October 23, 1889 Storm.” It would involve nearly a dozen ships, two states, multiple Life-Saving Stations, and would endure for nearly a week. Some pf these vessels caught in the storm were saved, and some were lost.

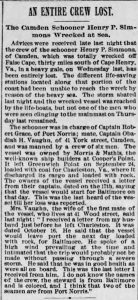

“October 23, 1889, was in general a very tempestuous month, but there can be little doubt that the most destructive storm experienced on the Middle Atlantic coast of the United States during the month was that which reached the shores of Virginia and North Carolina on the afternoon of the 23[rd], and raged with great violence…In three instances there was lamentable loss of life, the particulars of which are here given. The vessels involved were the schooners Henry P. Simmons, Francis E. Waters, and Lizzie S. Haynes; all three being wrecked within a few miles of each other, the first two in the night of the 23[rd] and the Haynes on the following day. The case of the Simmons was a peculiarly harrowing one…,”

So began the “Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1890” for the Sixth District.

The Context

Although the wreck and attempted rescues of the schooner Henry P. Simmons were, indeed, a peculiarly harrowing event, the story cannot be told individually, for it was a tragic part of a much larger event.

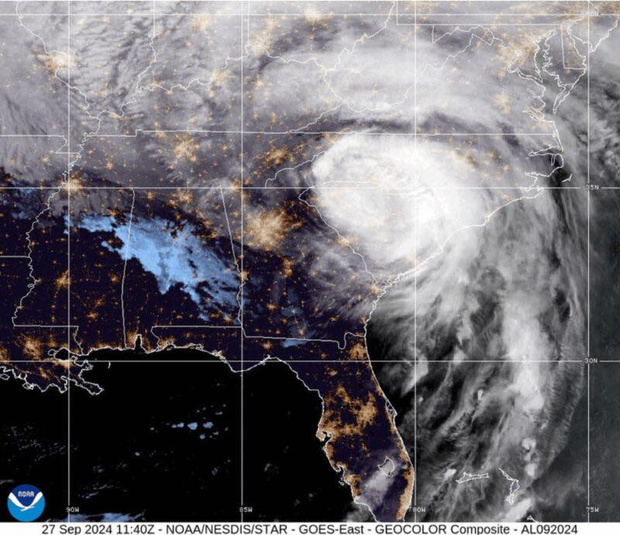

There are no records of a hurricane hitting the central U.S. coast on October 23 of 1889, but whatever it was and wherever it came from, a massive monster of a storm hit the area of the North Carolina-Virginia state line, stayed for nearly a week, and ravaged a small flotilla of ships.

Along North Carolina

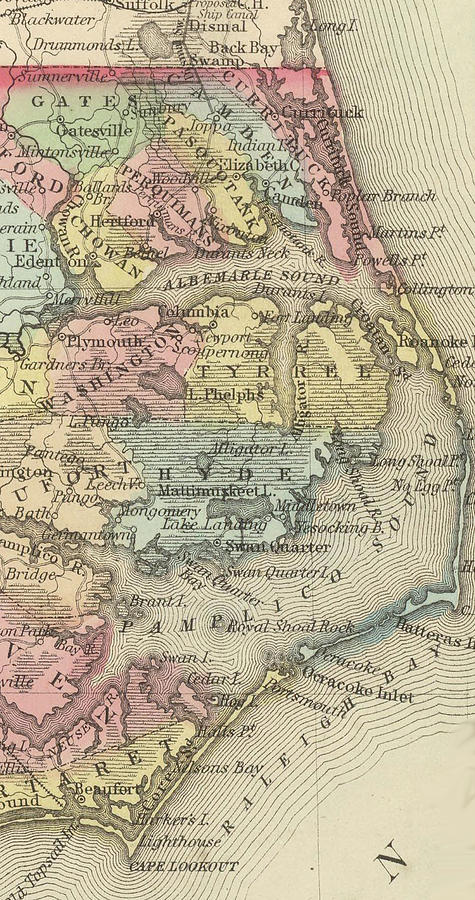

Wrecking within miles of each other on the northern-most coast of North Carolina were the Francis E. Waters, the Henry P. Simmons and the Lizzie S. Haynes. Two additional North Carolina wrecks nearby that day were the three-masted schooner Annie E. Blackman twenty-five miles to the south, and the 250-ton, three-masted British schooner Busiris, which wrecked somewhat further south, near the Poyners Hill Life-Saving Station No. 9.

The fate of the Francis E. Waters was described in detail earlier, with the dreadful loss of six lives. Then, only twenty-five miles to the south, was the bizarre incident of the three-masted schooner Annie E. Blackman. Also ensconced by this behemoth of a storm, and “invisible from the shore owing to the thick weather, was tripped by an unusually heavy sea and thrown upon her beam ends,” the same Annual Report tells. The seven crew members were swept across the decks into the raging sea, and six were gone instantly. The captain had earlier put on a cork life belt, which kept him afloat above the towering surf. Incredibly, he drifted through New Inlet and landed safely to a beach, tied himself to a telegraph pole, and was discovered by crew members of the New Inlet Station the next morning.

The wreck and rescue of the schooner Lizzie S. Haynes is a saga unto itself and will be told in detail in a later article. Some were saved, but some were lost.

Along Virginia

Just to the north of these wrecks, the Virginia coast claimed the sloop General Harrison, the original grounding of the schooner Henry P. Simmons, the British steamship Baltimore, and the schooner Welaka. One Virginia account also includes the coasting schooner Frank O. Dame. This, however, is clearly an error, as several reports, including the Boston Globe, report the wreck was October 12 not October 23.

The story of the Bridgeton, New Jersey sloop, (a sloop is a fore-and-aft rigged boat with one mast and a single jib), General Harrison is one of the shortest and happiest. Her crew saw the storm coming, anchored the General Harrison, and then went ashore in the sloop’s boat. The oncoming storm caused the sloop to drag anchor and come ashore northwest of the Cape Henry Life-Saving Station midmorning the next day. All were safe, and the vessel was able to be refloated.

The incident of the British steamer Baltimore was an equally short and happy story. She had simply run aground on an outer sandbar, sustained no damage, and was safely hauled off with all onboard well.

The short story of the 433-ton schooner Welaka was truly sad. Sailing from Georgia, it had earlier encountered a two-day storm which had caused some damage to the vessel. While trying to make repairs at sea, she was hit with the October 23 storm and ran aground amidst the rest of this melee. The British steamship Spendthrift began to tow Welaka off the sandbar, but the tow line broke and caused the two vessels to collide. The schooner’s captain had had enough, simply abandoned her, and sailed off on the Spendthrift. So much for the rest of the cast.

Now for the “Peculiarly Harrowing One”

The Annual Report again helps to introduce this epic and harrowing narrative: “The low beaches of Virginia and North Carolina were literally strewn with wrecks, and the hardy crews of the Sixth District were kept exceedingly busy saving life and property. The storm had come with such suddenness that many coasters were unable to reach a harbor, and this will account for the great number of casualties.”

The Ship

The Henry P. Simmons was a three-masted, 648-ton schooner with a length of 152 feet. She was built by the Morris & Mathis shipyard at Cooper’s Point in Camden, New Jersey, across the Delaware River from Philadelphia in June of 1884 with hull number 40 (of 216 built). The original and then current owner was Robert. C. Grace, who was also her master and commander on this fateful voyage. She had a crew of eight sailors and a cargo of South Carolina phosphate rock, used in making commercial fertilizer. She had departed Charleston, S.C. on October 17 with her heavy load, bound for Baltimore, Maryland.

The Wreck & Rescue

The tragic account of this harrowing encounter was told by the sole survivor of eight crewmen: Robert Lee Garnett.

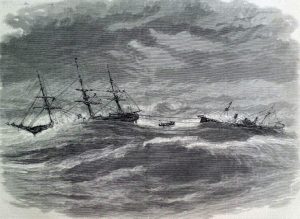

Seaman Garnett begins his account making note of their great progress and smooth sailing. He relates that “on or about October 17th” they departed Charleston bound for Baltimore. He was relieved to report they had safely traversed the dreaded Diamond Shoals and were only around 90 miles from the safe harbor of the Chesapeake Bay when “with no prior indication that a storm was approaching, a sudden strong easterly gale struck the schooner and by 8 o’clock that evening was blowing in gusts of hurricane intensity.” The winds struck so quickly and so strongly that the prevented the sailor’s efforts to take in sail, which is standard procedure as the first action in such a situation. Instead, they only had time to lash the helm midships, and then, for fear of immediately being washed overboard, they scurried up into the rigging. Now, with no steering, no crew to handle the lines and the sails, and in the midst of a ferocious storm, the outcome was inevitable.

But it took another two and a half hours for the Henry P. Simmons to run aground. Amazingly, this gave the crew time to occasionally descend from the rigging and to feverously work the pumps in their singular effort to keep their ship from sinking. When it finally hit, the Simmons was driven ashore near the North Carolina-Virginia state line. This was between the U.S. Life-Saving Station Wash Woods in North Carolina and the U.S. Life-Saving Station False Cape in Virginia. The schooner struck so viciously that “the top of her cabin was swept away by one of the first breakers that stuck and she soon settled in the sands until her hull was completely submerged—nothing but the three masts was left above water,” Garnett said.

The torrential rains that typically accompany a hurricane or fall storm continued all night, which is how the crew spent that night in the rigging. The torrents were so heavy that the men could not see where they were. Thoughts must have been running through their minds: Were they close enough to shore to wade in? Was there a Life-Saving station nearby? Was there any help around? Why have we not seen a distress flare or signal rockets? Why have we not heard the report of the Lyle gun? How long could we hold on?

Unfortunately, the last question was answered around 3:00 a.m. that night when, cold, weak and exhausted, the steward let go and fell into the sea and was swept away.

The Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1890 eloquently but graphically paints this picture: “When day dawned the scene from the rigging of the wreck was a wild and terrifying one. The wind still raged and the waves broke into surf as far offshore as the eye could see through the pelting rain and spoon drift, while to the leeward lay the low sand hills, which ever and anon came into sight and were then hidden by the towering billows that madly chased one another other shoreward, and were there scattered with thunderous roar into a smother of foam and spray upon the desolate beach.”

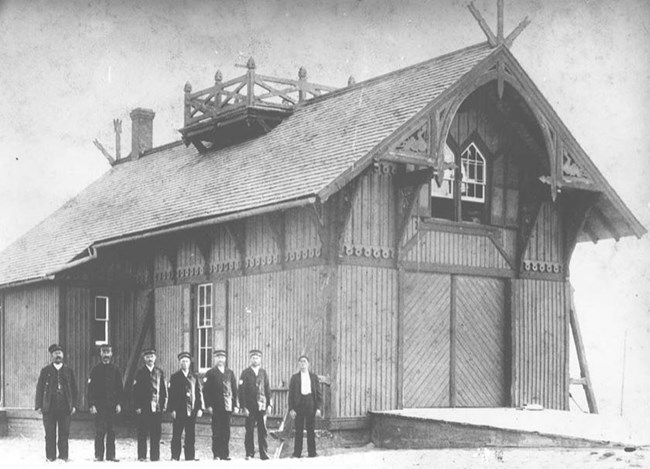

Ever vigilant, the Life-Saving Service were performing their routine duties. The Wash Woods station patrolman returning from his northern route reported seeing a faint light far offshore, but the raging storm made it impossible to discern what it was. The first morning patrol could now see a sunken vessel, but it was a great distance offshore. The Annual Report explains that “Under these conditions patrol duty was attended with the greatest difficulty and danger, the men having in places to wade hip-deep and being frequently driven to the knolls for safety.” This accounts for the extreme difficulty for the lifesaving crew to reach a place opposite the wreck with their bulky equipment, which they finally managed to do, arriving around 10:00 a.m.

By then, according to Garnett’s statement, as the lifesavers set up their equipment, the second mate fell in. An hour later, a third seaman fell. Before the day ended, another was lost. It was then determined that the vessel was 1,000 yards out to sea, far out of the range of the Lyle gun, and stranded in impossible conditions for the surfboat. The ultimate scenario of frustration for the lifesavers, as expressed well in the Annual Report: “Here, on the one hand, was a sunken vessel with her crew in the rigging, looking imploringly to the shore for help, and, on the other, a band of sturdy men skilled in the handling of boats in the surf and equipped with the most approved appliances for the saving of human life from the perils of the sea, but withal powerless to save. Yet this was the exact situation.”

It was now into the next day. Beginning at daybreak, “Three attempts were made on this date 26th to reach the Simmons but every time the boat was driven back full of water,” the prior Annual Report of 1889 states. Two more crewmen without hope or life fell in as no abatement of the weather occured. Finally, by that evening, the winds and seas began to lessen.

Yet another day passed. Now, there was but one sailor left in the rigging, and it was still not known if he was alive or dead. So, at 5:00 a.m. on the morning of October 28, the surfboat was again readied and manned “by the picked crew of oarsmen from the Wash Woods and False Cape crews including Keeper O Neal of the last named station and with the veteran keeper Malachi Corbel at the steering oar a bold and successful dash was made through the heavy line of breakers on the bar,” the 1889 Report continues.

The lifesavers reached the vessel, climbed aboard, and “To the great relief of every man in the boat a faint response came to the keeper’s hail, and presently there crept out into view the form of the sole survivor of the dreadful tragedy. He had been ensconced within the sheltering folds of the mizzen gaff topsail, and this protection, with the aid of a splendid physique, had enabled him to withstand the great hardships to which he had been ex posed. He had been without food of any kind for over four days, his only sustenance having been rainwater caught in the sail, and his survival was “simply marvelous,” per the 1890 Report.

The Exhausting Conclusion

The remarkable Robert Lee Garnett was succored at the Wash Woods station and incredibly had recovered enough in two days to leave for home in Virginia Beach. Five bodies were eventually recovered and given proper burials. Captain Grace’s body was claimed by his family.

This rescue would have been a “particularly harrowing one” in and of itself, considering the great distance from shore with the hurricane winds and waves. Yet this was just one of multiple wrecks that multiple stations and multiple lifesavers of the Sixth District responded to over multiple days near the end of 1889. That year, the above lifesavers were part of a total of 36 disasters that the Sixth District stations responded to, saving well over $500,000 worth of ships and cargo (almost $17 million today.) More importantly, they responded to 248 persons on board, and saved 229 (a 92% success rate) and succored 65 persons for 298 days.

These lifesavers responding to the Henry P. Simmons were a part of that group of United States Life-Saving Service surfmen: that amazing, remarkable, incredible, fantastic, heroic United States Life-Saving Service.