U-boat artifacts, divers reveal history of Torpedo Junction

As thousands of visitors joyfully play in the surf of Outer Banks’ beaches, a new exhibit at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum reminds us that a vicious German U-boat campaign in the early months of World War II had once raged offshore the barrier islands, setting the sea ablaze and filling the air with explosions.

While the Battle of the Atlantic from 1939 to 1945 was the war’s longest military campaign, it came closest to Cape Hatteras, where submarines would lurk in the sea off the shallow sandbars of Diamond Shoals to strike with devastating success at passing vessels.

“I envision the Battle of the Atlantic exhibit to eventually be the signature exhibit for the museum,” Joseph Schwarzer, director of North Carolina Maritime Museums, said in an interview June 29 during opening day of the exhibit that memorializes the U-boat campaign from a local perspective with many artifacts salvaged from Outer Banks waters. “Most people have no idea that this ever happened.”

Opened in 2002 on the south end of Hatteras Island, the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum is focused on four centuries of Outer Banks’ maritime and shipwreck history.

What makes the museum’s new Operation Drumbeat exhibit such a unique venue for telling the story of “Torpedo Junction” — as wartime ship captains dubbed Cape Hatteras — is that the museum’s location encompasses the area that experienced the war at its front door.

Cape Hatteras was targeted by U-boats because its shipping lane was close to the deep water of the continental shelf where the subs could hide. Forced to hug the coast to avoid wrecking on a shoal, the vessels were sitting ducks to lurking German U-boats. The area suffered the most casualties from U-boat attacks of any along the East Coast.

“Flaming tankers burned so brightly off the Outer Banks that on shore, it was said, one could read a newspaper by the glow at night, while the grim flotsam of war — oil, wreckage, and corpses — was strewn across local beaches,” the National Park Service wrote on its online site about Torpedo Junction, which was along what is now part of Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

Many artifacts in the Graveyard of the Atlantic exhibit come from the German U-85, the remains of which still rest in the ocean off Nags Head, about 60 miles north of Hatteras.

In the first half of 1942, during “Operation Drumbeat,” or Paukenschlag in German, the codename for Germany’s initial World War II assault against the U.S., 90 ships were sunk off the North Carolina coast — mostly off the Outer Banks — killing 1,600, including about 1,200 merchant mariners, according to the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary online information about the Battle of the Atlantic.

Much of the bloodbath in the early months went unanswered by the U.S., which underestimated the skill and scope of the German U-boat operation. The losses were so severe, Gen. George Marshall had said, that they threatened the entire U.S. war effort.

The tide started turning on April 14, 1942, when the Navy destroyer U.S.S Roper, with guidance from a new radar system spotted the U-85 on the sea’s surface, just 16 miles southeast of Nags Head. Between a combination of machine gun fire and depth charges, the Roper sunk the German sub, with the bodies of 29 crew later recovered.

Short for the German word “unterseeboot,” U-boats were used more as warships that mostly stayed on the surface and attacked with deck guns. When they were underwater, it typically would be for short periods to avoid detection.

The demise of the U-85 was the first successful surface attack by the U.S. Navy of a German U-boat since the war had begun in December 1941.

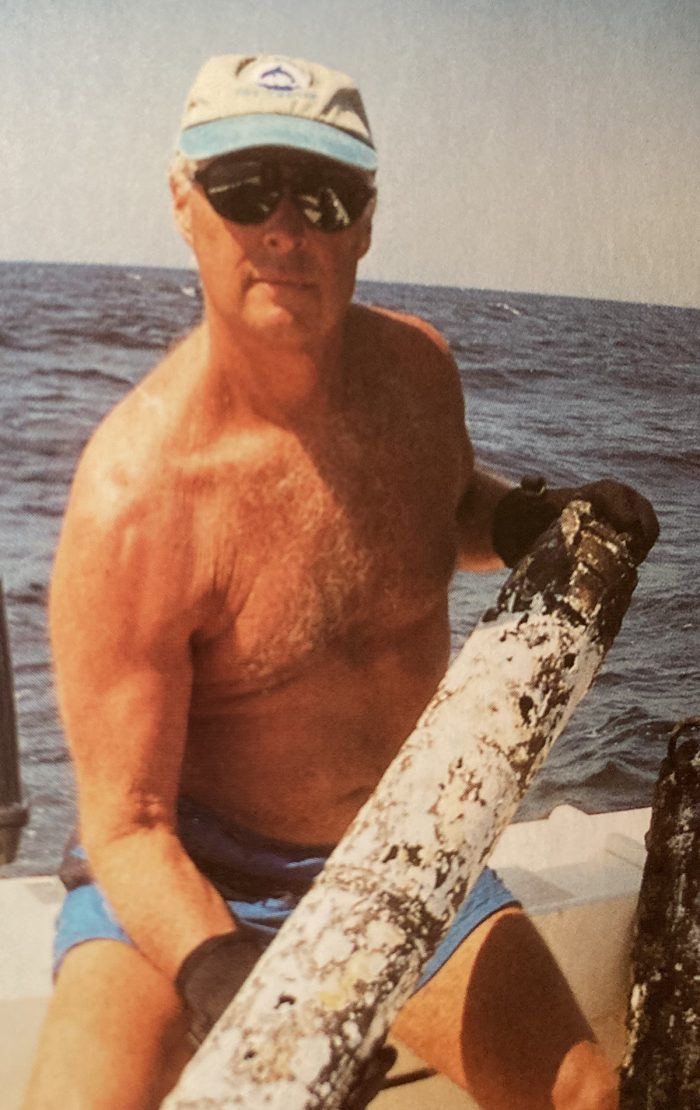

To the good fortune of the museum, Schwarzer said, local diver Jim Bunch of Dare County, along with Roger Hunting and his brother Rich Hunting, as well as Billy Daniels, have loaned numerous artifacts they salvaged during their many dives on the U-85.

“No one has ever seen this before,” Schwarzer told the roughly 75 opening-day attendees, giving a shoutout to the divers. “They really came through for us.”

The exhibit also includes a rare Enigma code machine that the divers had previously donated.

In a later interview, Bunch, who is 81, said he had made close to 1,000 dives on the U-85 over a period of 30 years. Accompanied by the Huntings and other diving buddies, Bunch said that they had recovered everyday items such as dishes, but also manuals and armaments. The meticulous work to retrieve the submarine’s contents was detailed in Bunch’s 2003 book “Germany’s U-85, A Shadow In The Sea” about the dives and the history of the vessel.

Although the Navy sent divers to the U-85 wreck shortly after it sunk — and many other divers after it was rediscovered in the 1960s by a Virginia Beach fisherman — Bunch and his friends were able to recover important items, including 88 mm deck gun rounds and an MP-40 machine gun. But to Bunch, the Enigma machine on display at the museum was probably the biggest prize.

“There were very few of those left in existence,” he said. “That one they have there was in a state of disrepair. Most folks who’d see something like that would think it was a piece of junk.

“We were just lucky we happened to come across it,” he added. “With the permission of the German government, we gave it to the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum. It’s probably the most significant piece of history to come from that wreck.”

Developed in Germany during the 1920s, the Enigma machine was an encryption device that was used by all branches of the German military in World War II to share battle plans and top secret information. But even before the start of the war, Polish cryptologists had cracked the cipher and continued to work to perfect decoding it with the French, English and later American intelligence. While constantly keeping up with changes in Enigma codes, the Allies were able to secretly read German communications, a critical contribution to defeat of the Nazis.

The exhibit also includes examples of male and female World War II-era Coast Guard uniforms, lifejackets, goggles and a toolbox, all from the U-85, as well as historic photographs and numerous armaments, depth charges and artillery. A large ensign flag emblazoned with the Nazi swastika, hanging on one wall of the exhibit, is a chilling symbol of the chaos wrought by the U-boats off our shores.

The exhibit also includes examples of male and female World War II-era Coast Guard uniforms, lifejackets, goggles and a toolbox, all from the U-85, as well as historic photographs and numerous armaments, depth charges and artillery. A large ensign flag emblazoned with the Nazi swastika, hanging on one wall of the exhibit, is a chilling symbol of the chaos wrought by the U-boats off our shores.

There are also several models of U-boats on display. By far, the most detailed was created by Michael Mills, a craftsman from Brunswick, Maryland. Mills, whom Schwarzer welcomed during the ceremony after Mills asked to be part of the exhibit, gave a slide presentation about his exacting work that went into constructing miniature depictions of every detail on the U-552.

Three days after the U-boat attacked the oil tanker Byron B. Benson in April 1942 off the northern Outer Banks, the vessel sank about 15 miles east of Duck.

“He’s not a modelmaker,” Schwarzer said admiringly of Mills, “he’s an artist.”

Bunch said that besides the U-505, captured intact by the Navy in 1944 and today displayed at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, he is not aware of another Battle of the Atlantic exhibit in the U.S. as compelling as the one at the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

“I like it,” said Bunch, a longtime member of the board of the nonprofit Friends of the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum. “I thought it was good. I don’t know what could be done to make it better.”

Bunch said there is also an interesting collection of U-boat artifacts at Olympus Dive Shop in Morehead City that were collected by diver and shop owner George Purifoy, who died in 2008 at 63. George’s son Robert Purifoy now operates the business.

The artifacts from the U-352, which was sunk in 1942 off Morehead City, are still on display, filling five shelves in a small case, said Dottie Benjamin, Olympus’ sales charter manager. Of the 100 or so items, she said, there’s china, shaving brushes and razors, boots, coins, buttons, a gas mask and a gun holster.

In addition to the U-85 and the U-352, there are the remains of two other U-boats, eight Allied naval vessels and 78 merchant vessels sunk off the North Carolina coast, according to the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary.

For Roger Hunting, also of Dare County and Virginia, who dove on the U-85 for about nine years, preserving the boat’s artifacts has turned into his life’s focus. As shown in Bunch’s book, Hunting carefully restored a second Enigma machine he recovered from the U-85 — one of 32 of the four-rotor machines known to exist — as well as an ornate toolbox and all its tools.

“I cleaned everything myself,” Hunting said in a recent interview. That involved treating every piece individually, which could include sandblasting.

“It took years to get all this stuff restored,” he said.

Hunting, 70, carefully documented, researched and photographed every item, many of which have been loaned to the shipwreck museum. From his research — “and that was before the Internet,” he noted — he knows where each item had belonged on the boat, and its purpose.

Pointing to a photograph of a long implement, Hunting explained that it was a voice pipe, or speaking tube.

“That came out of the conning tower,” he said. “The captain was in the conning tower when they were attacking a ship. He would call down the numbers to somebody who would calculate the depth.”

Of the 38 total artifacts from the U-85 loaned to the museum, the collection includes wrenches, a chisel, a cigarette lighter, a smoking pipe, rubber boots, board game pieces, jars of ointment with the contents intact, gas masks, a torpedo trigger, spare gun parts, microphone and headphones for the radio operator, coffee cups with swastikas and dates on the bottom, and a wooden name tag that was screwed into a locker.

All the items were salvaged before sunken warships gained federal protection in the early 2000s, Hunting said. Adding, the German government agreed in about 2003 to relinquish all control of the Enigma.

Whatever the future may hold for further donations, Hunting said that selling the artifacts isn’t in the cards. “Never,” he declared.

And Hunting didn’t entirely dismiss the possibility that additional U-boat artifacts might materialize from other U-boat divers looking for tax deductions for generous donations to the museum. But, for now, “maybe” might be the operative word.

“Divers are funny guys — they’re very possessive,” Hunting said. “We know lots of people who have very nice artifacts. But they’re not letting them go.”