UNC institute’s shark survey a trove of 50 years of data

Before “Jaws” with its depiction of a giant, vengeful, man-eating creature of the deep; before Shark Week, Discovery Channels’ eight-day ode to all things sharks; and well before the over-the-top gratuitous sci-fi series “Sharknado” films, there was, just off the coast of North Carolina, “shark survey.”

Not as glamorous, perhaps, as the mindless entertainment evoked from creative minds the likes of Steven Spielberg, the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City has achieved in the research world a treasure trove of data about shark species caught off the coastal waters of North Carolina.

Think of it as a kind of national archives of sharks — the result of 50 years of information compiled from catching the finned wonders using the same method of baiting in the two same spots in the Onslow Bay area of the Atlantic Ocean.

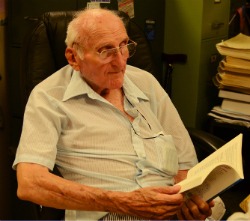

“Long-term data that has been consistent in methods that do not have gaps is extraordinarily rare,” said Steve Fegley, a retired research associate professor. “A lot of what we do: we can conduct research, we can sample for a couple of years, but then the questions we have about what’s going on, we really should be sampling for decades. What’s remarkable about this dataset is the methods that are used are consistent and the sampling is unbroken.”

The inception of the program goes back to the late 1960s when the late marine zoologist Frank Schwartz followed his curiosity from the lab to the waters outside of Beaufort Inlet.

The first year Schwartz put hooks in the water to catch his research subjects was 1972.

In those early years, the focus was solely on the fish.

Enter Fegley, who, before Schwartz’s death in 2018, came with a background in statistics, decided to take a look at the data researchers had collected over numerous trips.

“I started analyzing the dataset and participating in going out on the shark trips themselves,” Fegley said. “I started analyzing the data in ways it had never been analyzed before.”

Fegley wanted to show that, within that data, there was a host of information, things no one was talking about.

Around this time, Joel Fodrie, now the professor in charge of the institute’s shark survey, joined the ranks.

Fegley said his role in the survey was small, but one that helped bridge the program from Schwartz to Fodrie and a catalyst in showing people aspects of a dataset that had yet to be considered.

Advances in statistics during the prime of Schwartz’s career enabled researchers to begin examining water temperatures, surface salinities and wind and wave conditions, all of which help scientists get a more wholistic picture beyond the fin and what’s happening in the ecological system.

This is one of the hallmarks of the survey.

“I do think that there are lab groups that become very sharkcentric and everything they do primarily revolves around sharks,” Fodrie said. “That’s not really who we are. We like this extra challenge of bringing them back into the larger community of sea life. We think of ourselves as marine or fisheries ecologists first and then sharks are a part of that.”

Schwartz didn’t know it at the time he set out to start collecting information sharks — species, size and gender — but two large-scale events would directly affect sharks and their habitat.

The first is global climate change. The second, marine scientists attribute to the 1975 release of “Jaws,” a cinematic phenomenon that piqued the curiosity of humans the world over and spurred the harvesting of sharks.

The data collected in the early years of the survey allow researchers to ask questions about that critical time, Fegley said.

Over the past half-century, the data has shown broad-stroke patterns.

The first of which is that from 1973-74 through the 1980s more sharks were being caught and surveyed than now.

“Since the early 1990s and continuing up to at least about three or four years ago the overall abundance of shark has continued to decrease,” Fegley said.

Second, the different species of shark being caught in the survey has declined.

“Almost any time you do catch any sharks nowadays you can almost guarantee the Atlantic sharpnose shark,” Fegley said.

One graduate student’s research of the data found a trend in the size of many species of sharks caught within the past couple of decades being smaller than those caught in the late 1980s through the early 1990s.

Why that is remains a question yet to be answered.

Is climate change a factor? Conditions at the locations in which the surveys occur have, in a way, changed, Fegley said.

“It just may be that some of these shark species now prefer other areas that are nearby. We have a very clear picture of a very small spot. The other thing to consider is what these sharks are feeding on. Are we seeing fewer spot? Or, some of the different grunts? Or, some of the other fish that if their abundances are down then maybe it’s not a surprise that the shark abundances are down,” Fegley said. “We’ve got a very interesting, distinctive, significant pattern on several aspects. It would be foolhardy given this stage of analysis to say this is what’s going on, this is what it’s got to be. For us when you get a dataset like this it really does open up more questions than it does answers.”

The survey is amongst the oldest in the world.

Since 1972, from April through November, Institute of Marine Sciences crews travel to two sites 4 kilometers, or about 2.5 miles, offshore and 13 kilometers, or about 8 miles, once every other week.

This equates to 15 trips and 3,0000 baited hooks a year.

Just under 11,000 sharks have been caught, measured and analyzed. They’ve pulled in hammerheads, tiger sharks, bull sharks and a variety of Atlantic sharpnose species.

The program has allowed researchers to conduct a host of analyses.

Savannah Ryburn, a marine ecologist and UNC Chapel Hill student working on a master’s degree, is studying shark diets.

Ryburn was set to head to the university’s Center for Galapagos Studies on San Cristobal Island last summer before the COVID-19 pandemic shuttered travel.

Instead, she headed to Morehead City to begin carrying out her research through the shark survey.

She’s using a new method of testing to learn what sharks eat by taking fecal swabs from sharks, then using DNA analysis to figure out what the sharks are eating.

From June through the beginning of September, Ryburn swabbed sharks.

“Thankfully I was able to join the trips last summer and actually test my method and make sure it works,” she said in a telephone interview from the Galapagos, where she is working on gathering DNA from the samples she collected. “It’s a quick and noninvasive way to determine diet. I’m doing something pretty similar now. I’m still working on getting the DNA to the point where it can be read. I don’t have any concrete results yet.”

Ari Friedlaender, a long-term ecological researcher with the University of California, Santa Cruz, has worked with the Australian Antarctic Division and is part of the Long-Term Ecological Research program at Palmer Station, a United States station in Antarctica.

His work there is to get a better understanding of the ecological roles of whales in a rapidly changing environment.

Friedlaender, who earned his master’s in marine biology at the University of North Carolina Wilmington and doctorate at Duke University, has not worked with the shark survey, but understands the value of long-term research programs.

“When you’re studying long-lived animals like humpback whales … if you want to understand the impact of things like climate change or invariability in the environment you really need to have a long-term dataset,” he said. “If you only measure in a very finite window over a small period you may just be catching one end of a phase. To me there isn’t a status quo or a finish line for a project. The value of continuing to ask questions is they all build on the knowledge that was just gained.”

Fegley has now started taking all of the environmental data collected through the survey to predict what researchers will see in the future, including the abundance of shark and their sizes.

He’s depending on the future of the shark survey to see his research through.

The program has, in large part, been funded solely through the university. Grants are competitive and funding, in a general sense, does not always flow toward observational programs like the shark survey, Fodrie said.

“If we don’t have the program then that process stops before validation,” Fegley said. “If the program should survive and I don’t know that it’s under any eminent threat, but the threat is always there.”

Fodrie said the institute’s shark survey offers an important role in the detective work of the oceans.

“It’s already proven its worth, but will it keep proving its worth?” he said. “Without a program like this you might have people like me trying to understand an ecosystem and never really be able to tie in the sharks. In the normal day to day of putting out little nets or little buckets you’re not going to access those animals. For someone like me who wants to understand marine ecology that really leaves a large hole.”