Agencies meet on Hatteras Inlet shoaling, but struggle to find new remedies

If anything was clear after two hours with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on Friday discussing shoaling in Hatteras Inlet, it was that remedies will not come easy. And even rebuilding of the eroded Hatteras spit is on the table.

At the meeting in the Coastal Studies Institute in Wanchese called last week by state Sen. Bill Cook, R-Beaufort County, numerous officials with the Corps detailed the low odds of getting Congress to expand authorization to dredge more area in the inlet and the near-impossibility of finding more federal funds.

Cook, who represents Dare County, late last year had sent a letter to the Corps requesting that their current federal authorization, which dates back to the 1940s, be expanded in the waterway, so that areas, such as the problematic Inlet Gorge, could be dredged as needed.

Even getting to step one in the authorization process – a study — would be a difficult feat, said Christine Brayman, Corps deputy for programs and project management in Wilmington.

“I think we have to be realistic,” she told the panel of more than 20 federal, state and local officials. “The possibility of getting a new study start for this project is very, very slim.”

Bob Keistler, navigation project manager, compared authorization to a teen-age boy asking for a new car, and his parents saying, “Sure.” But without the funding, the new car – or dredging project – is unaffordable and unrealistic.

“I feel like I’m giving the last will and testament,” he said. “We’re between a rock and a hard place.”

With about the same number of people, including numerous Hatteras Island charter boat captains, listening in the audience, Brayman explained that the district’s last study start was for Wilmington harbor in fiscal year 2009-2010. Federal harbor maintenance projects are typically prioritized by commercial tonnage transported by vessels – leaving Hatteras way down the list. As it is, she continued, of the 1,000 harbors authorized to dredge nationwide, only about 200 to 300 annually get funding.

Brayman said if a study was done, it could be a multi-year, costly process that has no guarantee of getting anywhere.

“Everything has to be justified in the economics – that the cost savings justifies the cost of dredging,” she said.

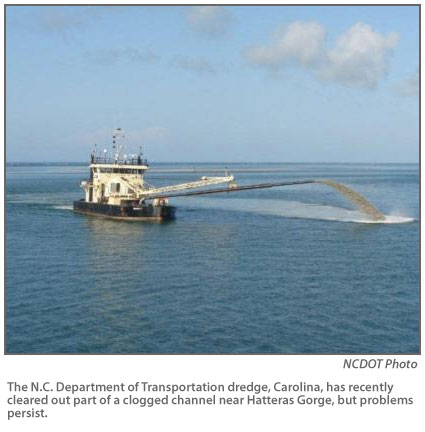

The biggest issue currently in Hatteras Inlet is an 800-foot shoaled section on the east side of the Inlet Gorge which is making it risky for boat traffic to get in and out of the inlet. The state dredge cannot safely work at the exposed spot, but it may be possible for a larger Corps dredge if the Corps had the authority to work there.

Although the state pipeline dredge Carolina recently had done some work at the Gorge, state Ferry Division director Ed Goodwin said at the meeting that he would not allow the state dredge to work there again.

“I will not risk anything in equipment and manpower to go beyond that,” he said. “We can’t do any more than we have done . . . We cannot go oceanside.”

But Keistler and others with the Corps said they will continue to work closely with Dare County and the state to find a solution.

“In essence, what we’re trying to do today is bring some synergy to a tough engineering problem,” said Kevin Landers, Commander of the Corps’ Wilmington District.

Landers encouraged continued partnerships with state and local governments. The Corps can do certain permitted dredging projects under agreements that provide funds.

Dare County has an inlet and waterways fund to do proactive dredging in Oregon and Hatteras inlets, and the state has a similar fund that provides a three-quarters match for what local governments pay. What’s missing now is the Corps authority to address the problem area.

“There’s going to have to be an alignment of political forces in this state,” Landers said. But without “rolling up sleeves and creative thoughts,” he added, “this inlet is going to kick our butt.”

It wasn’t until Hurricane Irene in 2011 that shoaling in Hatteras Inlet started getting bad enough to eventually hinder ferry and charter vessel traffic, said Roger Bullock, the Corps’ chief of navigation. At the same time, erosion of the Hatteras spit – about one mile has been lost since 2002 — has exposed more of the inlet to stronger currents, winds and waves. The combination of factors has made the channel boundaries authorized more than 75 years ago irrelevant.

The so-called short channel between Hatteras and Ocracoke islands that the ferries used until 2012 is still surveyed regularly by the Corps, he said. The Corps is looking at the possibility of developing a plan for advanced maintenance and possibly widening the channel. The longer route, a natural channel, takes about one hour versus about 40 minutes for the former route, costing more time and fuel for both ferries and charter vessels.

“We haven’t forgotten about Hatteras in any way,” Bullock said. “We haven’t stopped watching it.”

Over the last 20 years, the Point of Hatteras Spit has been steadily eroding, he said, but it didn’t start creating a problem until about a decade ago. Without the natural breakwater of the spit, the inlet is much less protected from powerful – and more dangerous – ocean conditions. Even large dredges, which are in essence self-powered barges — can be threatened in rough weather.

“This is not the first time,” Bullock said about Hatteras erosion. “Over a 100-year period, this point has retreated, grew back, retreated. That’s with anywhere: Does Mother Nature want that? It could come back, but maybe not in our careers.”

So perhaps it’s time to seriously explore rebuilding the tip of the island, suggested Dare County Commissioner Warren Judge. Without the hazard of exposure, the state dredge could more likely safely maintain the gorge.

“If we get it back to what is was before (Hurricane) Emily hit in ’93, this project gets simple,” he said. “Well, maybe not simple, but manageable.”

Dare County Manager Bobby Outten said that “back of the envelope” figures provided to him from the county’s beach nourishment contractor estimated that it would cost about $20 million to $25 million to restore the Point. And that is without any calculation of how long it may last or how to obtain the sand source.

Responding to Cook’s question about the possibility of instead using a terminal groin, Landers said that is likely to cost triple or quadruple of rebuilding. The commander also declined to say “off the cuff” whether or not the sand would stay if the work were done.

“So far,” Cook said, “I hear a lot of ‘There’s no way to do anything.’”

Added to the difficulty, the county would no longer qualify for an emergency permit to dredge Hatteras Inlet, said state Department of Transportation Division 1 maintenance engineer Sterling Baker.

“It has to be an actual state of emergency,” he said. “You can’t get a permit on the pretense that it’s going to be an emergency.”

Baker also said that it would require a different agreement to use a sidecaster dredge on the western end of the short channel. But with the ferries no longer using that channel, that is not a NCDOT issue.

For the short term, Jim Tobin, vice-chairman of the Oregon Inlet and Waterways Commission, said that the state and local agreement with the Corps to maintain the non-federal part of the channel with a sidecast dredge needs to be obtained. That agreement, he said, would require a study of submerged vegetation, which takes about nine months.

Landers promised to help however he could with the permit process. He also agreed to help find out more about the prospect of doing a study for a Congressional authorization change.

Steve “Creature” Coulter, a Hatteras charter captain, asked what the state could do in the meantime to take care of shoaling at the Gorge.

“Right now, we’re coming up on the season and we need a way to get out to sea in the next nine months,” he said.

But, for the time being, it all seemed to come back to square one.

“For us to dredge,” Bullock said, “you have to have a permit, and you have to have money.”