Federal appeals court hears oral arguments in Bonner Bridge lawsuit

One of the more down and dirty battles on the Outer Banks moved into the refined wood-paneled courtroom of a federal appeals court in Richmond, Va., today when attorneys representing both sides of the Bonner Bridge replacement issue argued before a three-judge panel on the merits of their case.

Unlike other yawn-inducing court hearings, this was akin to a free-wheeling sparring match between attorneys and the higher court judges, who continually interrupted the lawyers with pointed, persistent questioning.

The oral arguments at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit — with each side given a mere 20 minutes to defend its position — were the last step in the process of an appeal filed last October by the Southern Environmental Law Center against the North Carolina Department of Transportation and the Federal Highways Administration.

The Cape Hatteras Electric Cooperative was allowed to join as a defendant-intervenor because the environmental groups’ preferred alternative – a 17.5 bridge that bypasses Pea Island – would require prohibitively expensive transmission lines under the bridge.

Typically, the appellate court issue rulings in about 60 days.

Even so, the exhaustive 25 years of studying, planning, filing and responding to lawsuits that has transpired during the effort to replace the 51-year-old Herbert C. Bonner Bridge over Oregon Inlet will continue unabated.

A hearing on a separate legal action by SELC against the state Coastal Resources Commission has been scheduled for November. Construction on the bridge will be frozen at least until that matter is resolved.

Representing the Defenders of Wildlife and the National Wildlife Refuge Association, SELC attorney Julie Youngman argued on Tuesday that the state violated environmental laws by analyzing the Bonner project in segments and by selecting an alternative that was not the least harmful to Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge.

On Sept. 16, U.S. District Court Judge Louise Flanagan issued a 42-page ruling that rejected every claim made by the law center in a 2011 lawsuit challenging construction of the replacement project. The plaintiffs filed an appeal on Oct. 1.

The DOT attorney, John Maddrey, and the Highways Administration attorney, Robert Lundman argued that the National Environmental Policy Act did not forbid projects to be done in phases and that the chosen bridge alternative minimized harm to the refuge. They also said it was the most prudent, affordable option for replacing the critically aged bridge.

The appellate panel — Judge James A. Wynn Jr. from Robersonville, N.C; Judge Allyson K. Duncan from Durham; and U.S. District Judge Michelle Childs, a designee from South Carolina — asked questions at will and frequently followed up after expressing confusion or a lack of understanding of the attorneys’ arguments.

Observers sitting on the four rows of benches in the small courtroom, parsing every utterance from the judges, included numerous Dare County residents and public officials.

Unfortunately for the court-watchers, the line of questioning produced no clear insight into where the judges’ sympathies lie.

While questioning Youngman, Wynn wondered that even if the short bridge alternative was selected with one of the studied Highway 12 maintenance alternatives, wouldn’t that satisfy one environmental rule, but not the other? What about if we say okay, build the bridge, he continued, but make the second part of the project subject to an Environmental Assessment?

“Are you asking to start over?” Duncan interjected.

Responding, Youngman said that the defendants “need not hide the ball” and should provide the details of the entire project, not just the bridge replacement.

In several back-and-forth exchanges, Duncan repeatedly tried to determine if the plaintiffs were asking that the project be remanded –sent back – for more suitable conditions.

“They can be directed to consider a short bridge alternative, but they need to consider it in full,” Youngman replied.

In referring to Flanagan’s statement that the $1 billion upfront payment for the long bridge the SELC favors was cost prohibitive, Duncan asked Youngman if that was “clearly erroneous.”

“I believe it is,” Youngman replied, pointing to the funds available for the planned bridges in Pea Island and Rodanthe.

In his argument, Lundman said that the final environmental statements included a transportation management plan that detailed all the different alternatives that the agency considered, as well as how the project would be done in phases as needed. What it did not do, he said, is say exactly what would be done when on the later phases of the project, which includes Highway 12 south of the bridge to Rodanthe.

“It’s hard to make those choices because of the dynamic nature of these islands,” he told the judges. “It doesn’t make sense to spend $300 million where there may not be a breach.”

Wynn asked again if it would be possible to build the bridge and choose an alternative that has been studied for a later phase.

“I’m just trying to figure out why this all fell apart,” he said. “I’m not following what’s going on.”

Duncan chimed in, elaborating on Wynn’s questioning about the feasibility of doing the project while staying within the bounds of the existing studies.

“If you deviated from that, then a statement gets done,” she said. “It’s not a reversal, it’s an affirming.”

“I’m all for an affirming,” Lundman said, inspiring the only laughter of the hearing.

Maddrey then explained to the panel that the transportation plan describes what will happen after Phase I, that is, construction of the new bridge. The selected alternative, he said, provides the flexibility to respond to the current conditions.

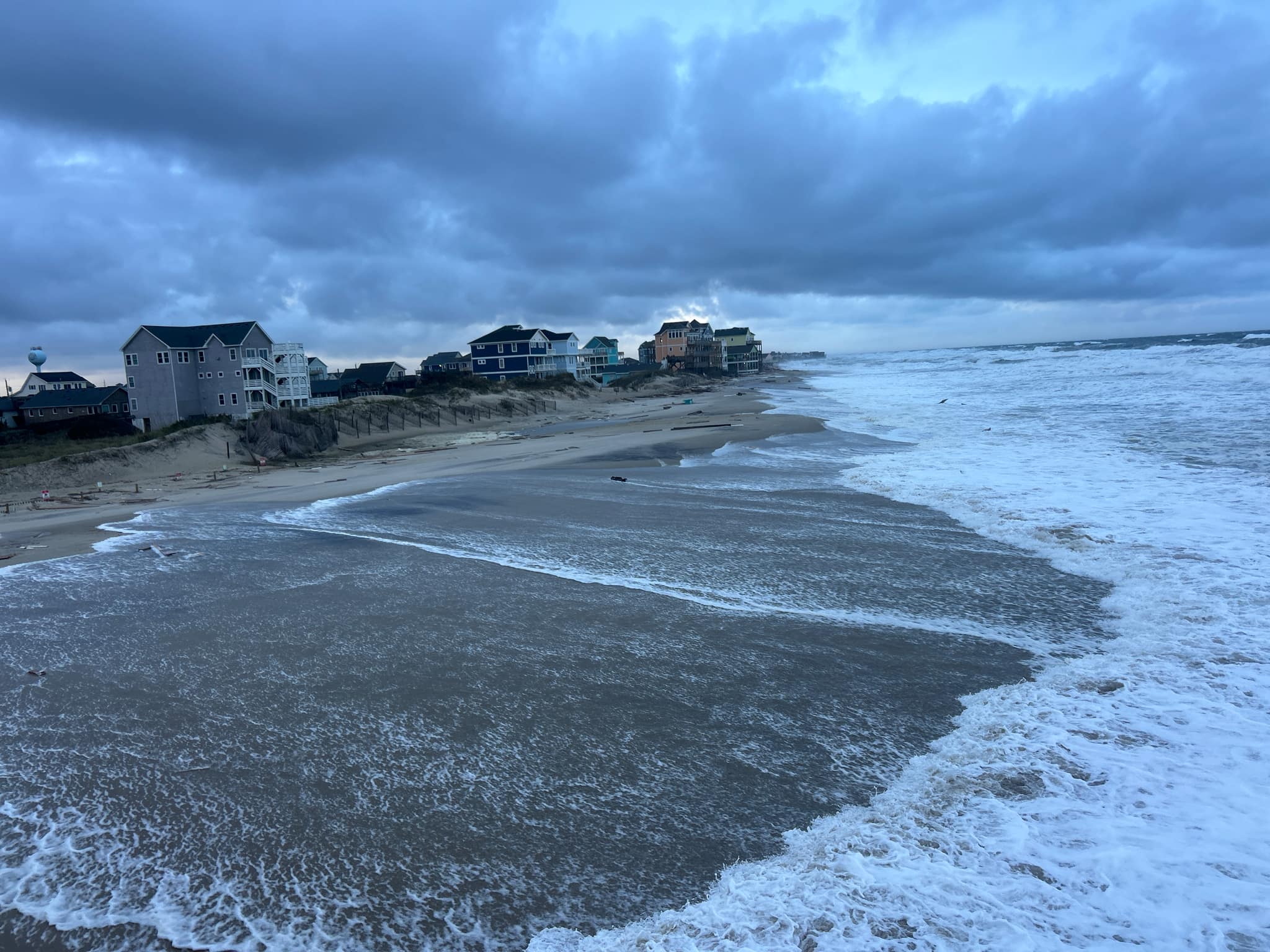

But Wynn questioned how the road would survive the coastal conditions.

“You know Highway 12 in the next hurricane is gone,” he said.

Maddrey responded: “Those breaches that came after Irene validates the decision.”

After the hearing, Derb Carter, director of SELC’s North Carolina office, declined to say what his reaction was to the questioning, other than note that the court was making inquiries of both sides.

“We think the court seemed to clearly understand the key issues of the case,” he said, “which is very encouraging.”

Warren Judge, chairman of the Dare County Board of Commissioners, didn’t hesitate to state his opinion.

“I’m glad we had the opportunity to be in court today,” he said. “It always amazes me how the Defenders of Wildlife has no regard for the human life that uses the bridge.

“I feel confident that NCDOT is in the right,” he continued. “I just believe that right will prevail.”

As to what the panel will decide, it’s kind of like forecasting the weather, said Norman Shearin, a Kitty Hawk attorney who is representing the Cape Hatteras Electric Cooperative.

Shearin, a partner with Vandeventer Black, said he has argued about 10 times in front of the appellate court during the course of his 40-year career. Since he willingly gave up his allotted time to the transportation attorneys, he said this is the first time he got to be an observer in the Court of Appeals.

“I was not discouraged by the arguments,” he said after the hearing. “They were a very active and candid panel. So often, you don’t get insight into what the judges are thinking.”

Simply put, Shearin expects that the panel will affirm the lower court decision and remand it. But that encompasses numerous possibilities. They could require additional studies by the agencies. They could accept Flanagan’s ruling outright. They could modify it and specify the conditions.

“But there really isn’t any way,” he said, “to predict with certainty what they’re going to do.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

For more information on the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, go to http://www.ca4.uscourts.gov/oral-argument/oral-argument-calendar.

To listen to an audio of the hearing, which should be available in two days, go to http://www.ca4.uscourts.gov/oral-argument/listen-to-oral-arguments.