If the ferries can’t run to and from this southernmost Outer Banks island, the community is isolated, and its tourism economy crashes.

It’s a threat that has become all too real.

Since about mid-March, persistent shoaling in the Bigfoot Slough channel off Silver Lake Harbor has resulted in temporary cutbacks in the schedule for Cedar Island and Swan Quarter ferry service, the tolled routes to the island popular with travelers coming from the west and south.

The reduced schedule was extended Monday through April 12, as an Army Corps of Engineers dredge continues work to clear the channel.

Meanwhile, a worsening hot spot along N.C. 12 on the north end of the island has been damaged and repaired so often it is nearly unsalvageable. But if the next storm destroys that section of the island’s only highway, it will leave vehicle traffic on the island with no access for many months from Hatteras, the busiest of the state’s eight ferry routes.

To coastal residents who view ferries as their version of bridges or mass transit, operation of the vessels is critical to their economic survival and passage to the rest of the state. But the final report from the NC First Commission, an ad hoc panel established in March 2019 to advise the state’s transportation secretary in the formation of a sustainable long-range investment strategy, offers little comfort for those worried about the condition of the ferry system — nor the ability of the fiscally starved North Carolina Department of Transportation, which oversees the Ferry Division, to address it.

According to the report, “North Carolina is facing a trifecta of transportation investment crises: determining the appropriate investment amount, identifying and securing viable revenue options to meet short-term infrastructure needs, and creating a long-term, sustainable investment strategy to replace an eroding 20th century revenue model.”

Overall, NCDOT’s increasingly severe budget stress came to a crisis point just before the pandemic and has since then only been aggravated by revenue losses due to COVID-19-related shutdowns and drastically decreased travel. Findings in the NC First final report in January warned of a future of rising construction costs, eroding motor fuels tax base and increasing risk of diminished federal revenue.

The annual budget for NCDOT is currently $5.1 billion. More than 75% of the department’s funding comes from what NC First characterizes as outmoded and depleted sources: the Motor Fuels Tax, the Highway Use Tax and Division of Motor Vehicles fees. Some also comes from federal fuels taxes.

Several different funding methods the report looked at could include implementing new user fees, increasing highway use and other taxes and fees, and eliminating certain exemptions.

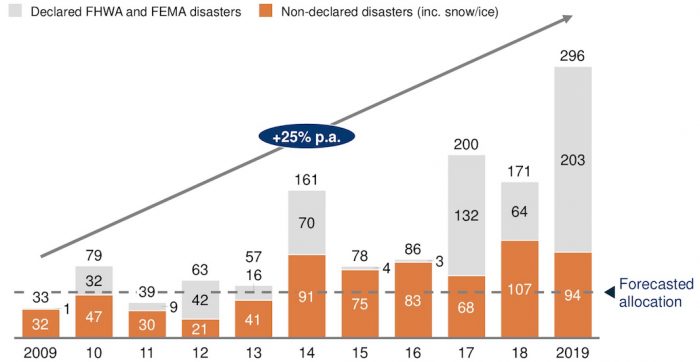

Another big contribution to NCDOT’s budget woes has been a precipitous number of annual declared and nondeclared disasters. In 2009, the number of disasters statewide totaled 33, but in 2019 there were 296. There were 161 disasters in 2014, 200 in 2017 and 171 in 2018. Prior to 2013, disaster recovery costs averaged about $50 million annually, which matched what the agency had budgeted. But costs have since skyrocketed to an average of $165 million a year. In 2019, disaster costs jumped to $296 million.

But, as the report detailed, many of the disasters did not qualify for federal emergency disaster funds. As it is, the state has not been able to keep up with even routine maintenance of the vast amount of roadway for which it is responsible.

“North Carolina is the ninth most populous state and it maintains the second highest state-owned highway mileage in the nation,” the report found, “yet it invests far less than nearly any other state, ranking 44th for per-mile investment in state-maintained roads. The following analyses of multiple metrics from eight peer states reveal that North Carolina comparatively underfunds transportation in state-maintained roads.”

Considering the negative ramifications of a deteriorated transportation system, the report recommended that the state increase funding for NCDOT by a minimum of $2 billion a year, or $20 billion over the next decade.

Although “NCDOT leadership is working through the biennium budget process,” according to a recent email from Jamie Kritzer, a department spokesman, it is not yet clear how much of the transportation needs will be addressed by June 30, when the North Carolina General Assembly finalizes the state spending plan.

“The budget will reflect DOT’s most important priority,” he wrote, “which is maintaining a safe transportation network for the traveling public.”

Kritzer added that the Ferry Division continues to seek “opportunities to enhance service through improved business practices and more efficient processes,” including vessel upkeep.

In the Ferry Division alone, according to the NC First report, unmet needs include 63 maintenance, capital construction and IT projects. Projects range from rehabilitating, replacing or adding vessels to expanding and/or improving ferry terminals.

In fiscal 2020, the division spent $57.1 million to operate seven year-round routes and one seasonal route, as well as storm-related emergency evacuations and deliveries. Ferry toll revenue is used to pay for new vessels.

“The Ferry Division plans on vessel replacements based on vessel age and frequency of maintenance being incurred,” the agency said in a recent email, responding to an inquiry from Coastal Review. “On average, replacement projects cost $18 million for Sound Class and $14 million for River Class and Hatteras Class vessels. There are nine vessels that, based on current conditions, have been identified to have rehabilitation projects performed that would extend the life by 15 years. On average, the approximate cost for a rehabilitation project is $10 million.”

Plans to replace two 31-year-old river-class ferries, the Chicamacomico and the Kinnakeet, are underway, according to the email. The Silver Lake, a 52-year-old sound-class vessel, is budgeted to be replaced in 2024. The Croatoan, which is 17 years old, the Cedar Island, which is 26 years old, and the Carteret, which is 32 years old, have been identified for rehabilitation within the next few years.

Tolling the currently free-to-ride Hatteras-Ocracoke ferry route or other tolling changes would have to be recommended from a coastal regional planning group and is “not on the department’s agenda at this time,” the division email said.

Despite numerous obstacles to ferry ridership in 2020, including COVID-19 restrictions and a temporary closing due to a ramp project at Southport, there were still 480,581 vehicles that rode the ferries statewide. Of those, 185,565 used the Ocracoke route.

In 2016, NCDOT, working closely with the National Park Service and Hyde County, did a study of the Ocracoke hot spot, which extends about 5 miles south from the ferry terminal on the north side of the island, confusingly known as South Dock, from where the Hatteras Inlet ferry operates.

Severe erosion and storm damage has affected not only the hot spot — one of six identified in 1991 on N.C. 12, the only highway on Hatteras and Ocracoke islands — but also the channel the ferries use as they enter the terminal from Pamlico Sound.

Ocean and sound surge during storms, especially tropical storms and hurricanes, has repeatedly destroyed the dunes along N.C. 12 at the hot spot and sometimes the pavement, resulting in prolonged closures and expensive repairs.

Solutions proposed in the 2016 study included beach nourishment, bridging and road elevation and/or widening, but DOT never moved forward with the plan.

A study addendum with a seventh alternative was released in April 2020 that proposed relocation of the Hatteras Inlet terminal to north of Ocracoke Village. Although the alternative was identified in the 2016 feasibility study, it did not provide any specific information on locations, impacts or designs. The new study provides detailed descriptions and findings.

The proposed new ferry terminal defined in the addendum would be located 6 miles north of the village and one mile south of the Pony Pens where the National Park Service keeps Ocracoke ponies in a large, fenced area on the west side of the road. Under the proposal, if the old terminal is decommissioned, all N.C. 12 pavement and structures between the new and old terminals would be removed. Officials with Cape Hatteras National Seashore, which except for the village, owns most of the land on the island, have also expressed interest in expanding the pony area if the pavement is removed.

No action has been taken on the proposal, Kritzer said in the email.

“Currently, the N.C. Department of Transportation does not have an identified project or funding at this location,” he said. “A project of this nature will have to compete and be funded through the State Transportation Improvement Program (STI).”