Hatteras Island’s Recycling Crisis is a Symptom of a Larger Problem

In a depressing way, Hatteras Recycle is a microcosm of the current crisis in the U.S. recycling industry, and the urgent need for people to rethink what they throw in recycling bins.

In a depressing way, Hatteras Recycle is a microcosm of the current crisis in the U.S. recycling industry, and the urgent need for people to rethink what they throw in recycling bins.

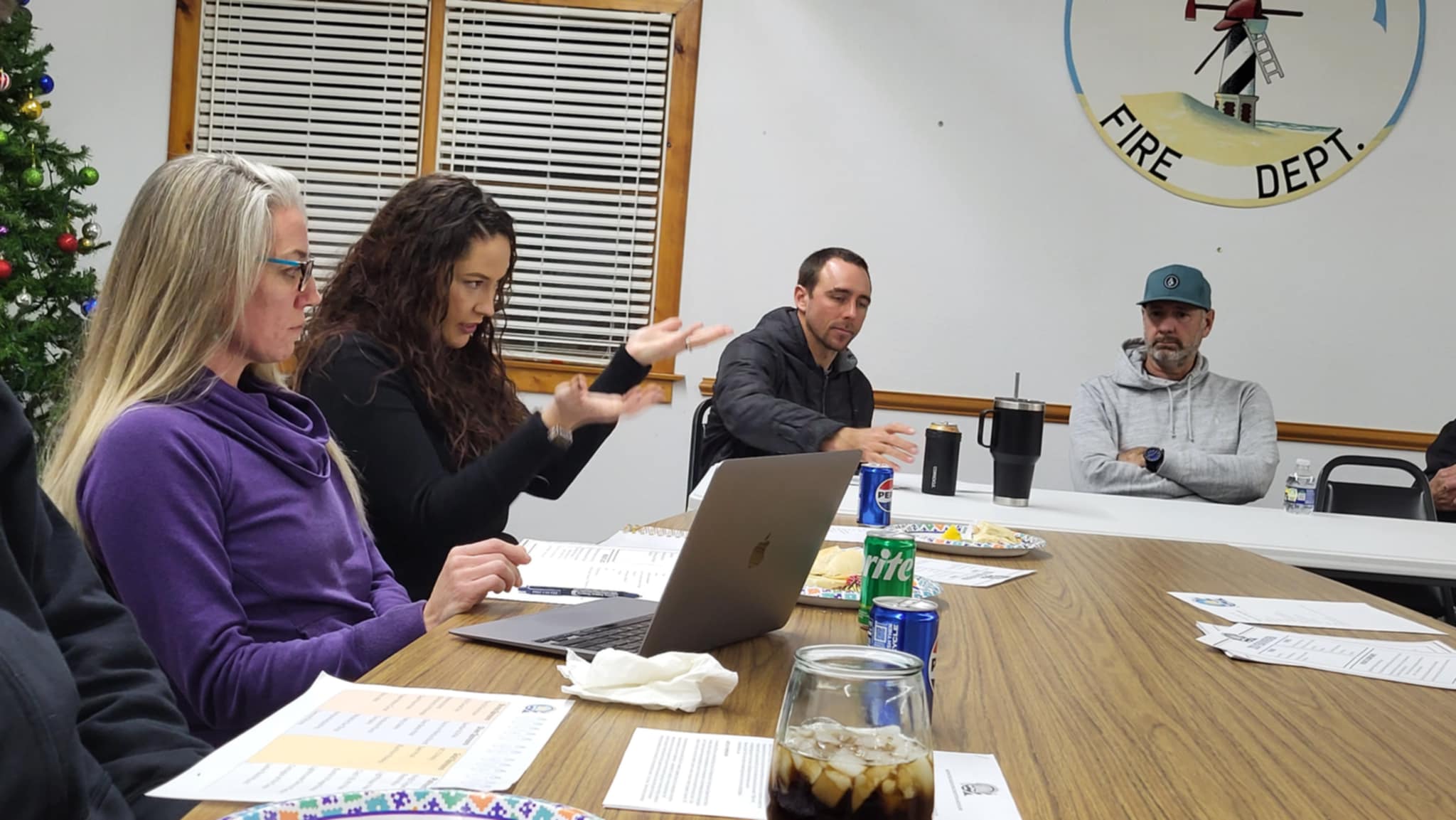

Owners Beth and Peter Eady, who bought the business in January, are already confronting steep spikes in tipping fees they’re charged, forcing them to increase fees to their customers. At the same time, the need for uncontaminated product is thwarted by some customers who take co-mingling to its careless extreme.

“We’re struggling,” Beth Eady said in a recent interview. “We’re going to have to see at the end of the year where we stand financially. If we can keep the stream clean, that’s the biggest thing.”

As a private business serving a small resort community whose population explodes in the summer, Hatteras Recycle, which provides curbside pickup service for about 1,500 rental properties and 300-400 local residences on Hatteras Island, has less cushion to absorb the stress created by the collapse in the recycling markets in 2017 when China cut off most imports of recyclables, blaming dirty and unusable product.

Extrapolating just from what Eady says she has seen tossed into their recycling carts, it’s easy to imagine the extent of the contamination problem. Whether it’s thrown in due to laziness or ignorance – “I think it’s a little bit of both,” she says – trash mixed in with recycling has included dirty diapers, filled dog waste bags, pee-pee pads, fishing bait, fish parts, fishing line, plastic pool toys and spoiled or leftover food. And that’s besides the slew of plastic shopping and garbage bags that also contaminate the recycling.

When previous owner Todd Phillips first started Hatteras Recycle in 2007, he was being paid $25 a ton by Bay Disposal & Recycling in Powells Point, says Peter Eady. Before Phillips sold to the couple, he was paying Bay Disposal $45 per ton to take the recyclables. Now the Edys have been informed that the tipping fees are being raised from the current $75 a ton to $95 a ton.

“It’s just been a year like no other,” says Phillips in a recent telephone interview from his home in Massachusetts where he lives. Phillips still maintains a financial interest in the business.

Phillips said in an interview late last year that Hatteras Recycle collected 425 tons of material in the 2018 season, from Easter through Thanksgiving.

In response to Bay Disposal no longer accepting glass, Hatteras Recycle this year has asked commercial restaurant customers to separate out glass bottles, and residential customers to dispose of glass at collection sites in Buxton and Rodanthe. The added benefit is that removing the weight of the glass decreases the tonnage costs.

Also, Dare County has a glass crusher, and the crushed glass is offered for free to the public to use.

Meanwhile, the business has printed flyers to distribute to summer rental companies and local businesses with information about what is and is not recyclable. Eady says the couple is still hopeful that the situation will improve, both in the industry nationwide, and in public awareness.

Ivey Johnson, who has operated Dare Area Recycling Technologies (D.A.R.T.) , a metal recycler, in Wanchese for 14 years, is also optimistic that the industry overall will bounce back.

“I see the big boys creating new markets, finding new buyers,” Johnson says. “I think we need to reposition ourselves as top dog.”

But for now, recycling in the U.S. is undergoing an industry version of a gut-twisting churn. Plastics, glass and cardboard are no longer accepted in many overseas markets, and pallets of crushed plastic and paper waste are warehoused while mad searches are conducted for a place to send it. Even countries that still accept U.S. recyclables are now demanding only clean product.

Just recently, Indonesia sent back 57 shipping containers filled with recyclables contaminated by garbage and incompatible or unacceptable material, according to an Associated Press report published on July 9. The majority of the containers were returned to Australia, the U.S., France, Germany and Hong Kong because their contents violated Indonesian laws that forbid importing toxic waste, the AP said. More shipments of recyclables from wealthy nations, the report said, have been going to Southeast Asian nations since China banned plastic waste imports two years ago.

An article detailing the impact of the Chinese plastics ban in the June 2018 journal Science Advances said that more than half of recycled plastics had been exported to hundreds of countries, with China taking about 45 percent of cumulative plastic waste since 1992. Between 1950 and 2017, a cumulative total of 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic has been produced. With the ban, an estimated 111 million metric tons of plastic waste will be displaced by 2030.

“Only 9 percent of plastic waste has been recycled globally, with an overwhelming majority of global plastic waste being landfilled or ending up contaminating the environment (80 percent),” the article said, “resulting in an estimated 4 million to 12 million metric tons of waste plastic entering the oceans annually.”

Things got even worse for U.S. recycling markets in 2018, when China instituted its National Sword program that banned imports of a total of 24 types of recyclables, including mixed paper and eventually all plastics because of widespread contamination.

Recycling programs across the U.S were put on notice while the industry scrambled to find new markets. But there have been no easy answers. According to a June 21 article in The Guardian, the equivalent of 19,000 shipping containers of plastic recycling per month that used to be exported is now stranded in the U.S. Much of it will end up in landfills.

North Carolina and South Carolina are in a better position than most states because they have a strong plastics recycling industry in place, says Micki Bozeman, Brunswick County Solid Waste and Recycling Coordinator.

The county has also been protected somewhat from market shocks by contracting out most of its recycling programs, she says, and by going out to bid every three years. For instance, the county has just issued a request for proposals for its electronics recycling program. It also seeks grant funds to offset higher costs of recycling old TVs and other outmoded, heavy electronics.

“We found keeping the contracts in place really help, especially if the markets go south,” Bozeman says.

For the time being, Bozeman says that Brunswick will continue its comingled recycling program, which ranked 12th in the state in 2018 for tonnage per capita , but it is stepping up educational efforts for the public with brochures and programming.

It’s a new world, and people need to know they can’t just throw everything together and ship it off. Now it is essential for recycled products to be clean and to be disposed of where they belong, she says. But different items can be recycled in different communities and states, and often consumers are confused.

For instance, she explains, most people don’t realize that glass windows and wine glasses are not recyclable glass – and in fact they would contaminate glass bottle recyclables.

Being more responsible for what goes in the recycling bin is an adjustment for the consumer and the businesses, Bozeman says. But with more sorting and materials recovery facilities, and more educational resources for municipal and county operations, she also sees it as an opening for new domestic businesses.

“I think it’s going to take everybody’s effort,” she says. “I think it’s an opportunity to build the recycling industry. The whole idea is to produce recyclable material that can be recycled to a new material.”

North Carolina currently does not allow plastic bottles, aluminum cans, pallets, electronics or oyster shells to be disposed of in landfills. But recycling is not mandated in the state.

In an educational campaign targeting the counties, the state will launch a new initiative called RecycleRightNC in the fall, said Mike Greene, recycling business development specialist for the state Division of Environmental Assistance and Customer Service.The state already has educational printable brochures and posters available online to help the public understand what and how to recycle.

The point is to make people aware in order to bring down the level of contamination, in turn helping to restore profitability for recycling, Greene said.

“Most of it is not a malicious act,” he said. “It’s what we call ‘wish recycling,’ such as tossing in clothing and garden hoses.”

In the earlier days of recycling, Greene said, everyone got used to separating certain disposables in different containers. When recycling switched to single-stream disposal, it increased recycling overall, but it changed people’s good habits.

“What we’ve done is we’ve gotten away from education,” he said. “Where with co-mingling everybody thought they throw out everything that’s not disgusting.”

Greene said that the state is working to help counties individualize information for what is acceptable for each recycling company, while also standardizing recycling imagery and language across the state.

Along with education, he said the state is also promoting an enforcement aspect that involves a warning tag and ‘three-strikes’ approach. There are also state grants available to encourage building of processing facilities and recycling businesses in counties.

Greene said the industry in North Carolina is adjusting, and the demand for recycled products is starting to come back.

“It will recover in time,” he said. “It’s a temporary crisis and I think we’re re-building it the right way.”