Officials Seek Long-Term Plan to Save N.C. 12

As sea levels continue to rise, the most imperiled spot on North Carolina’s vulnerable Outer Banks is likely on Ocracoke Island, where an erosion hot spot threatening its sole highway is past due for a long-term transportation solution, including potentially bypassing the north end of the island.

“I’d say on N.C. 12, this is probably the top priority, if not very close to the top priority,” Paul Williams, North Carolina Department of Transportation Division 1 environmental officer, told members of the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission during its April 28 meeting, which was held virtually.

“Just seeing what the precarious situation is,” he continued, “you’ve got ferry access to this island that needs to be maintained, and Hatteras access is essential.”

But N.C 12, the two-lane highway perched mere inches above sea level, squeezed between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pamlico Sound and stretching nearly 65 miles on Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands alone, has numerous issues and needs an overall long-term plan, Bob Woodard, chairman of the Dare County Board of Commissioners, said during his opening comments at the April 19 meeting.

“And that’s not in the mix right now,” he said. “We’re reactive.”

Woodard said he had initiated the formation of the N.C. 12 Task Force as a collaborative body to develop a long-term plan with resilient solutions to address current and future challenges “related to storms, erosion and sea level rise.”

And we’re going to try to identify funding strategies and a timeline for implementing this,” he said.

Members will represent task force partners Dare County, Hyde County, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge and the North Carolina Department of Transportation, and a stakeholders group will include members of the public and from other interests such as nonprofit and community organizations. It is to meet monthly.

“There’ll be all kinds of folks involved,” the chairman said. “We need to touch base with every single entity that this would impact.”

Williams, who was named as a member of the N.C. 12 Task Force, said that part of the essential work for the panel will be updating previous feasibility studies that were completed by the former Outer Banks Task Force. That panel, which met on and off from the early 1990s until it was eventually replaced by the Bonner Bridge replacement merger team, included representatives of numerous agencies as well as coastal scientists.

Its work led to studies of the six erosion hot spots identified in 1991 on N.C. 12, including the one on the north end of Ocracoke. Over the years, projects were done to address some of the most vulnerable spots, including road relocation and beach nourishment. But Williams said that much of the data from those studies will have to be updated.

A big hurdle for NCDOT right now is funding, and Williams said he is hopeful that the new task force will be helpful in finding sources of money for projects such as the long-term solution for Ocracoke. The transportation department will keep repairing the dunes, putting in more sandbags and fixing the road as long as it can, he said, but it can’t go on indefinitely.

“These sandbags are temporary,” he said. “We don’t intend to leave them there in perpetuity.”

At the same time, erosion has created severe problems at South Dock ferry basin, where the Ocracoke-Hatteras ferries come in on Ocracoke Island’s north end.

In his presentation to the Coastal Resources Commission Wednesday, Williams described how the same area on N.C. 12, about 5 miles south of the ferry terminal, had been battered by storm after storm for three years in a row, often undoing sandbag installation and rebuilt dunes and sometimes roadbed repairs that had recently been completed.

According to NCDOT records for Ocracoke, the last repair project, including 6,350 linear feet of sandbags, that was completed in February cost about $1.7 million. The total costs for N.C. 12 storm-related recovery on Ocracoke from 2010 to 2021 is $15,142,646.

“And it’s only a matter of time before something catastrophic happens and South Dock is cut off from the rest of Ocracoke Island,” he said. “Everybody’s aware of the necessity of having that connection to Hatteras Island for Ocracoke.”

An addendum completed last April to a 2016 NCDOT feasibility study of long-term solutions to the erosion on the north end of Ocracoke added two alternatives — Options A and B of Alternative 7 — that would bypass the north end of the island and construct a new ferry terminal about mid-island near where the National Park Service Pony Pens are located. Differences between the options include a bridge to the terminal and a location in deeper water.

According to the addendum, the new terminal location would add about 15 to 45 minutes to the current one-hour ferry ride between Hatteras and Ocracoke, depending on the vessel used. As a result, the number of ferry trips per day, per vessel would be reduced. The difference could be made up with additional ferries and staff.

Vehicles would have a shorter ride to the village, but only off-road vehicles would have access to the north end of the island because the paved road would be removed and used as an extended area for the ponies.

Costs for new terminal options range between $57.2 million and $87.2 million, not including costs for additional vessels, staff and fuel.

Williams said that the project is currently being scored by rankings in the State Transportation Improvement Program, or STIP. If it scores well, the project would be scheduled in the program, and the process of securing engineering and permitting could begin.

“Because of COVID(-19), there’s a lot of delays in getting projects scored right now,” he said. “There’s still budget constraints with DOT, so I don’t know what the outcome of that scoring will be, or what the chances are of this project getting funded anytime soon.”

With the state’s new focus on resiliency, Williams said he is optimistic that the N.C. 12 Task Force will be able to find some funding pot.

“Everybody seems to be very enthusiastic about looking at solutions for N.C. 12 on a long-term basis, really focusing in on resiliency as a reason for funding some these potentially really expensive projects,” he said. “Under the current STIP formula, it’s going to be really hard to fund really big projects with N.C. 12.”

But even if a giant pot of money for the project magically appeared tomorrow, there is still a lot to be worked out about engineering and design decisions.

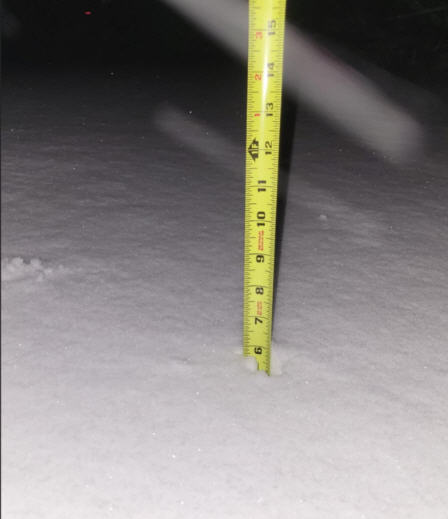

Workers repair damaged dunes along N.C. 12 in March on Ocracoke Island. Photo: Mark Hibbs

For instance, the National Park Service, which owns most of the island except private property in the village, would consider whether it would be beneficial for the Silver Lake ferry traffic to also use the new terminal.

But that is just a potential option, said Cape Hatteras National Seashore Superintendent Dave Hallac.

“We do support the most sustainable solution for solving the South Dock crisis,” he said in an interview, saying that a single terminal situated in deep water is among numerous ideas, but not one that anyone feels strongly about.

“We think it’s worth further exploration,” Hallac added.

Hallac emphasized that he wants to work with the community and is open to hearing all ideas. But the increasing rate of erosion on the north end of the island doesn’t provide the luxury of time.

“Some may say that terminal may be a terminal to nowhere soon,” Hallac said.

Justin LeBlanc, chairman of the Ocracoke Waterways Commission, said that the Hatteras-Ocracoke ferry operation is critical to the island’s tourism-based economy. Eighty percent of the ferry traffic to Ocracoke comes from Hatteras, he said, and that route represents half of the traffic in the entire state ferry system.

“The Hatteras Inlet ferry route is facing numerous challenges,” he said. “I don’t know if (the new terminal) is the right answer or not. I do know that the village of Ocracoke has not been as engaged in that conversation as it needs to.”

In general, the community needs to hash out the best option, agreed Randal Mathews, the Hyde County Board of Commissioners member from Ocracoke, and to have their ideas and concerns taken seriously.

At least one villager thinks that if the ferry terminal was moved and the road taken up from the north end, “that’s the end of Ocracoke,” Mathews said. Whether or not that viewpoint is shared by others is not clear, he said, but at this point in the process, there’s no consensus on the island about the best approach.

As someone who fishes, kite boards and surfs, Mathews says he understands the complexity of the island’s environment, and appreciates the need to protect it.

“I just have a hard time accepting that we’re going to let part of Ocracoke go back to nature,” he said. “Somebody is apparently pushing this. It’s not anybody on Ocracoke.”

There are still a lot of questions to be asked and answered about beach nourishment, bridging, dredging, submerged vegetation, and other options and issues, said Mathews, a long-time resident who is married to a native islander.

“I think we’ll work well with all these agencies,” he said about public input into the proposed plan. “But don’t give us lip service. Don’t even ask that want my input and then go ahead and make your own decision.”

As a 40+ year visitor and 33 year LIFE member of NCBBA I don’t understand all the band aid repairs that that been used on Hatteras Island NC 12 . We all know that the ocean is reclaiming the land/sand on NC 12 on Pea Island………why not use the same thinking used in the Florida Keys……….and overseas highway????? From the Basnight bridge install an elevated highway all the was to Rodanthe??

@Mike Metzgar_463260…Because that would make too much sense. Easiest way to fund is with tolls. Sock it to the tourists and allow for an annual toll pass to be purchased if anyone wants one.

My money is on….nature….you will never contain nor win against it….

Like swimming upstream…..