Time Span: Recalling First New Inlet Bridge

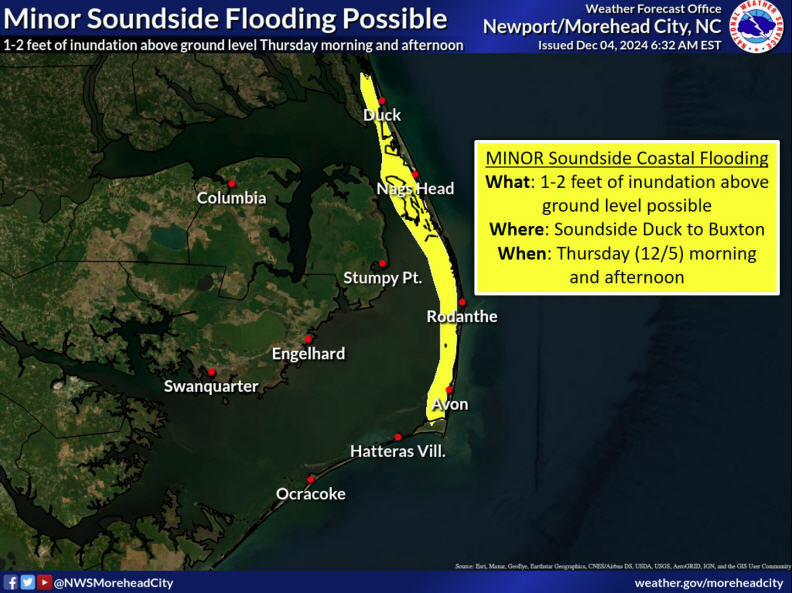

Hurricane Irene made landfall near Cape Lookout Aug. 27, 2011. As the storm tracked across eastern North Carolina, the waters of Pamlico Sound first drained to the south and west, flooding the coastal mainland. When the winds shifted, a 6-foot-high wall of water crashed onto the dunes of Pea Island, flowing across the sand toward the Atlantic Ocean.

At the “S” curves of N.C. 12 north of Rodanthe, the breach was a series of relatively shallow streams connecting the sound and the ocean. Farther north, in an area that had historically been a pathway to the sea, Pamlico Sound was once again open to the Atlantic.

Between 25 and 30 feet deep and 100 to 150 yards across, New Inlet had reformed where it previously existed time and time again and where an early bridge linked the barrier islands.

“New Inlet … has opened, closed, and shifted over the past four centuries of recorded history. Secondary sources record New Inlet as open — with dates not necessarily precise — between 1657-1683, 1738-1922, and 1932-1945,” historian Marvin Brown of AECOM Technical Services wrote in a 2016 architectural evaluation of Pea Island for the North Carolina Department of Transportation.

When Hurricane Irene reopened the inlet, it also severed N.C. 12, the only road connecting Hatteras Island with the northern Outer Banks.

NCDOT moved quickly to remedy the situation, bringing in a temporary bridge. Similar in design and concept to the portable Bailey Bridge developed and used during World War II, the structure could be quickly assembled and, when no longer needed, its components could be taken apart and moved to a new location.

By December 2011, Hatteras was again connected to the rest of the world, and six years later, in November 2017, a 2,350-foot-long span later dedicated as the Richard Etheridge Bridge opened to traffic. But the Richard Etheridge Bridge is also considered a temporary bridge. With a projected lifespan of 25 years, NCDOT is already exploring options for its replacement, a 100-year bridge that goes around Pea Island, according to a 2015 legal settlement protecting the refuge.

What remains of the first bridge over New Inlet is almost 90 years old now and is largely forgotten, even by longtime Hatteras Island residents. The old pilings are still there, wooden remnants of that earlier attempt to span one of the most dynamic areas of constantly shifting Pea Island.

It is that bridge that Brown evaluated in 2016 to determine whether it was eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Listing would mean that the remaining bits of structure would be protected when a permanent bridge replaces the Richard Etheridge Bridge.

Brown ultimately concluded that the bridge, or bridges, as he discovered in his research, were ineligible, writing, “… due to loss of all built features, the roadway is recommended as not having sufficient integrity to support NRHP eligibility either individually; as a contributing part of the (Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge); or as part of any other potential historic district.”

Although the bridges and remains of connecting roadway have lost the features that would qualify for federal protection, they represent a transitional time on the Outer Banks.

In 1922, New Inlet had closed after what may have been its longest open period: 185 years. Sometime around 1925, with New Inlet filled in via natural processes, Capt. Toby Tillett, a commercial fisherman from Wanchese, created his Oregon Inlet Ferry Service. By 1928 he was offering scheduled trips across Oregon Inlet between Hatteras Island and the northern Outer Banks, according to Outer Banks historian David Stick.

That alone may not have been enough to motivate the state to act, but other players were entering the game.

Also in 1933, the Roosevelt administration created the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC, with its mandate to put young men to work on environmental projects. At the same time, artist Frank Stick, David Stick’s father who moved to the Outer Banks in 1929, was pushing for a national park on Hatteras Island that would preserve the seashore.

The elder Stick began working with Conrad Wirth, a landscape architect and conservationist who had recently been hired as an assistant director for land planning for the National Park Service. Wirth would eventually become the Park Service director and held the position when the Cape Hatteras National Seashore was established as the first national seashore in 1953.

Wirth and Stick, according to a 2007 park service history of the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, shared a vision of stabilizing the shoreline by creating sand dunes, sand fencing and forestation. The most readily available labor pool was the CCC.

In 1934, Stick told the Elizabeth City Independent, that “excepting the appropriation for the airport at the Wright Memorial and that for restoration work at Fort Raleigh, the $640,000 so far allocated by the Public Works Administration between Currituck and Carteret will be for beach rehabilitation in the interest of preventing erosion through sand fixation and reforestation.”

Stick told newspapers that there would be a few thousand CCC workers coming to the Outer Banks, an exaggerated figure, but there was going to be a large contingent of young men coming to Hatteras Island, if they could get there.

Fairly quickly, in 1934 or 1935, NCDOT’s precursor, the State Highway Commission completed its bridges over New Inlet. The record of exactly when the bridges opened or any of the contracts associated with it seem to be lost to history, although there are photographs that have survived.

Additional evidence that the bridges were built by the State Highway Commission is the wooden stringer method of construction used for the spans. At one time a common technique in bridge building, the method had the added advantage, especially in North Carolina, of using readily available timber. When built using treated wood, typically with creosote, a 25-year lifespan could be expected.

Wooden stringer bridges were so important to the Highway Commission that it established strict standards for their construction.

“What was new in the 1920s was that the state’s standard plans and specifications ensured uniformity of design and economical use of material by contractors and state maintenance crews working across all regions of the state. The earliest surviving examples of timber stringer highway bridges in North Carolina are of the standard design adopted in June 1928 (Standard 600-C—Standard Creosoted Wood Superstructure with Reinforced Concrete Floor and Rails),” Brown wrote.

Decades later, those standards were still in use by the Highway Commission, according to its 1946 biennial report to the legislature.

Today, from the vantage point of N.C. 12, it appears as though the old structure is a single bridge running roughly parallel to the highway. From the air, however, it’s clear that the span consisted of three bridges, a detail Brown had noted in his report.

“At the two structures across the north and south channels, three vertical … parallel, round, wooden posts or piles—set perpendicular to and driven down into the sound … A shorter, squatter, simpler structure crossed a narrow inlet south of the two larger structures called the South Slew,” he wrote.

The three spans were a viable means of crossing New Inlet, according to newspaper accounts from the time. But conditions at the inlet continued to change, fluctuating from nearly completely closed to as wide as 1,000 yards across after a hurricane in 1944. By 1950 the inlet was again closed and remained so until Hurricane Irene.

After World War II, the Highway Commission began paving the road from Hatteras to Oregon Inlet. By 1952, the task was completed, and the wooden bridges across New Inlet faded into obscurity.