A celebration of the restoration and relighting of the Bodie Island Lighthouse….WITH SLIDE SHOW

Sometimes reporters get attached to the subject of their coverage, especially if that subject is an underdog unjustly outshined by another that’s taller and more popular.

The Bodie Island Lighthouse has been that underdog for me.

On Thursday evening, the fully restored lighthouse was officially relighted, and it opened today for the first time to the public for climbing.

It seems nothing short of a miracle.

When I gazed up this week at the newly-restored brick beacon, it took my breath away. It looked brand new. The black-and-white bands were spotless. No rust blighting the metalwork. No broken windows. No ugly orange tape encircling the base.

The setting was equally impressive, with the grounds tidied up and the sidewalks repaired. At the entrance to the lighthouse road, two small historic buildings moved from the beach have been restored, providing a fitting introduction to the historic district about one mile inland. And the Keeper’s Quarters adjacent to the lighthouse, now a bookstore and gift shop, has also been restored.

But the most impressive improvements are inside the 156-foot tall tower.

The oil house, once the office for the lighthouse keepers, has a fresh coat of bright white paint that contrasts against the wooden floor, painted gray-blue. Across the hallway, the oil room, with its original marble and slate flooring, has been repainted, its windows and ceilings replaced and its cabinets restored.

A new silver rail leads down the few steps to the base of the tower, its door propped open by a piece of granite recovered from the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse during the 1999 relocation project. Standing in the enclosed hole where the clock work once stood – a perfect spot, we joked, to corral misbehaving children – the view upward was as striking an image one could expect in a lighthouse.

“That’s what makes this lighthouse special,” said Doug Stover, historian for Cape Hatteras National Seashore. “It’s the visuals of the staircase.”

When you look up the inside of the Cape Hatteras tower, he said, the staircase is not as open because the stair treads are closed. But with Bodie, the progressively narrowing twist of the staircase is discernible all the way to the top through the open iron mesh of the steps.

When I used to drive south on Highway 12 from Nags Head in the late 1990s on my way to Buxton to cover the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse relocation project, I would see Bodie’s black-and-white bands peeking over the marshes just before Oregon Inlet.

Back then, especially with all the attention focused on the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, Bodie Island was virtually ignored. Yet, at night its blinking beam still swept the sky.

In 2000, when the National Park Service took the still-handsome tower under its wing, I got my first close-up look at the Bodie lighthouse. Its metal work was rusted and fragile-looking, and water drips were evident in rust streaks and mildew stains on floors, walls, and ceilings. There were bricks missing, wires holding pieces of iron together, cracked walls, windows patched with wood.

Nonetheless, it was majestic. But the most awe-inspiring thing about the tower is what few get to see — the first order Fresnel lens that has been at the top since the beginning.

A few years after the Coast Guard transferred the lighthouse to the Park Service, I was able to climb the tower for the first time. As I approached the lantern room, it was very warm, since there was virtually no air circulation. Little rainbows were dancing off the walls.

Standing on the platform, I was taken aback by the spectacular immensity and extraordinary beauty of the lens. The prisms are clear green and do magical things with light, refracting and reflecting minimal illumination into a potent beam. The largest of the the Fresnel lenses, the first-order lens is 12 feet high and more than 6 feet in diameter. It was considered an engineering feat when it was built in 1871, and it is no less a feat today.

I’ve been rooting for the Bodie Island Lighthouse ever since.

Numerous efforts were conducted over the years to get the tower the attention it so desperately needed. Restoration funds were finally put in the 2008 budget, but in a cruel twist, were pulled at the last minute. The recent restoration had to be stopped when damage was discovered in the gallery room under the lens, leaving lighthouse lovers despairing about yet another setback. Fortunately additional funds were found to complete the project, and the restored lens was returned to the top.

In 2010, I was able to climb part of the scaffolding on the exterior of the lighthouse to observe the restoration that was underway. Workers had removed numerous pieces of corroded iron to be repaired or replaced at a foundry. Later, they sand-blasted the rust-pitted metal decking and railings, using a shroud to catch the debris.

The inside now is gleaming with shiny black railings and spanking clean repainted white-brick walls. Window sills, once covered in black paint, have been stripped down to their original marble. The 214 steps from the ground to the lantern room have been repaired or replaced, and extra support brackets have been installed.

Unlike the staircase of the 208-foot Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, which is more attached to the interior walls, Bodie’s stairs sway a little as you ascend, especially close to the top.

After being subjected to limewash, a cleaning process that allows bricks to breathe, the walls no longer sweat water.

“Before,” Stover said, “it was like a rain forest in here.”

As a way to cut down on water leakage, he said, the new windows were made in one piece and do not open.

As he climbed the seven levels of the restored staircase, Stover pointed out the three stair treads he once had to leap over to avoid falling through cracked metal.

At the top, Stover pointed out the window where extra support cables were left in place and additional support brackets were installed. Under the lens, he showed the spot where the wooden beam had shifted.

“So sooner or later, it would have collapsed,” he said about the beam. And ultimately, the pressure would likely have cracked all the prisms in the lens.

The escorted public tours to the top of the lighthouse will stop short of the lantern room because of the fragility of the Fresnel lens and the tight quarters at top.

But the public will be able to go out on the balcony off the gallery, where they will be treated to one of the best views on the Outer Banks — a panorama of the Atlantic Ocean, Oregon Inlet, Pamlico Sound, the Bonner Bridge and the unspoiled marshlands surrounding the lighthouse’s original 15-acre tract.

The 42-inch high railing on the balcony has been reconstructed with its bars closer together to prevent little heads from getting stuck.

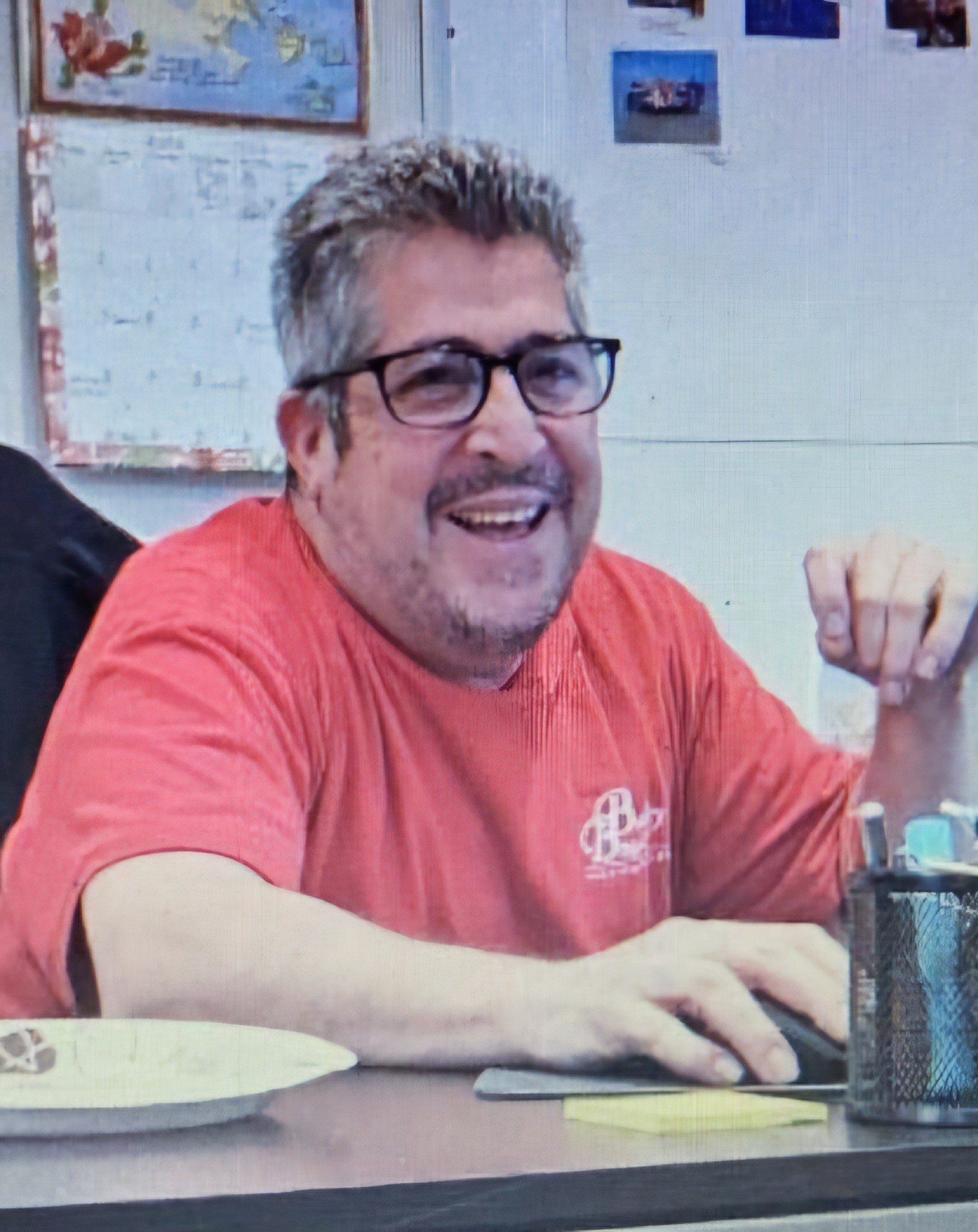

Back inside, Stover showed off the polished brass plaque at the base of the lens, not long ago green and tarnished. Of any of the Park Service staff, Stover, who arrived in 2000, has been closest to the restoration project.

“This has been his baby now for 13 years,” Cyndy Holda, a park spokeswoman, said as Stover grinned happily.

A rainbow splashed against the wall, covering Stover in bands of colored light.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Click here for information about touring the Bodie Island Lighthouse

CLICK HERE TO VIEW SLIDE SHOW