By Petty Officer 3rd Class Joshua L. Canup

Beneath the roiling waters of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, thousands of ships rest in a salty graveyard. For hundreds of years, mariners have nicknamed the area the “Graveyard of the Atlantic” based on the history of ships lost in its waters. Even for experienced Coast Guard members, traversing the area can prove a difficult task.

“It’s an extremely challenging area,” said Petty Officer 1st Class Joe Hagel, a coxswain at Station Hatteras Inlet. “You have two major currents colliding right on top of the shoals, and this causes them to constantly shift. What might have been navigable water one week has become hazardous the next. Unless you’re familiar with the area’s recent changes, it can be very difficult to navigate safely.”

Even with current technology such as radar and GPS, navigating the waters during a storm can be an intense challenge. The wind and rain and the chaotic swells can impact the crews’ visibility and communication.

“I’ve had to yell just to communicate over the wind, which is throwing rain at us almost sideways,” said Hagel, recalling his experiences carrying out missions in the rough weather. “Storms come up so quickly; it’ll look sunny at dawn and be a storm by the end of the day. The waves also are steep and close together, creating this washing machine effect where they come at you from all directions.”

Hagel is just one in a long blue line of service men and women that have journeyed into stormy conditions along the Outer Banks to rescue mariners in distress that have run aground.

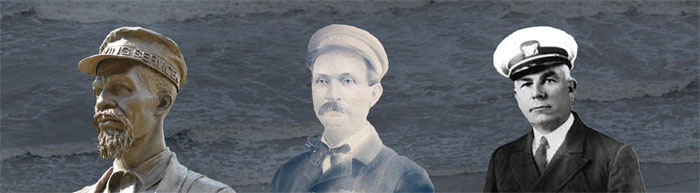

Members of the U.S. Life-Saving Service, which merged with the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service in 1915 to form the modern Coast Guard, battled similar conditions along the North Carolina coast. With old-fashioned tools at their disposal, LSS members relied on determination, physical strength and willpower.

On Oct. 11, 1896, Keeper Richard Etheridge and his crew at the Pea Island Life-Saving Station responded when the schooner E.S. Newman’s crew ran aground in a hurricane. Etheridge and his crew began to set up a line cannon, a device that fired a rope to mariners to help them get ashore. Yet every time they tried to set it up, it sank in the soaking wet sand. The waves themselves were too fierce for Etheridge’s crew to deploy their wooden rescue rowboat.

Forced to improvise, Etheridge relied on his crew’s training and tied rope to his three strongest swimmers. Relying on human muscle alone, the surfmen made their way out to the schooner and saved the entire crew. It took nine trips.

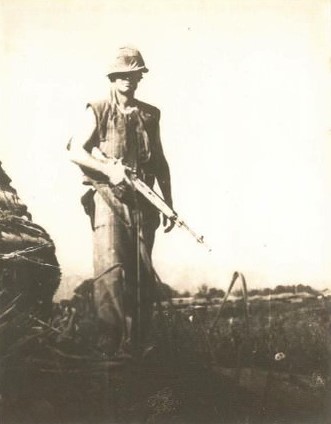

Later, on Aug. 18, 1899, Surfman Rasmus Midgett, a member of the Gull Shoal Life-Saving Station, left the station to begin a beach patrol during an approaching hurricane. After walking 3 miles, Midgett discovered the ship Priscilla, which had been run aground by winds up to 100 miles per hour and broken apart on the beach. With the ship split in two, 10 survivors were clinging to the back half of the shipwreck, shouting for help as violent waves crashed over the wreck.

The Priscilla wrecked roughly 3 miles from Midgett’s station, so walking back for assistance would use precious time – time the mariners might not have. Weighing his options of risking his life or returning to the station for assistance, Midgett leaped into the swells. Yelling instructions to the victims and swimming between swells, Midgett managed to bring them ashore one by one. After saving all 10 men, Midgett ensured that they were brought back to the station, where warm food and shelter awaited them.

In time, many successors of the Outer Banks’ Life-Saving stations would follow in their predecessors’ footsteps, enlisting in the LSS and, later, the Coast Guard. In 1918, while the world was engaged overseas in World War I, one such descendant, Keeper John Allen Midgett, was standing watch at the Chicamacomico station when disaster struck.

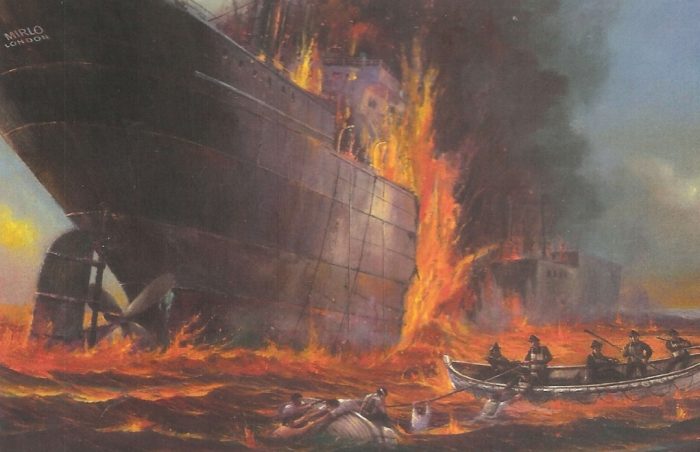

The German submarine U-117 torpedoed the British tanker SS Mirlo near Chicamacomico. The ensuing explosion could be seen for miles and sent fuel pouring into the water around the tanker. Midgett and his crew prepped their wooden motor surf boat and began their journey to the tanker.

Midgett had not received training on how to respond to fuel spills, nor had any of his crew. The liquid fuel technology was relatively new at that time, so no such training even existed.

Midgett improvised and steered the boat into the flames, smoke and extreme heat, determined to fulfill his duty of saving lives. The crew struggled through smoke and heat with one crewmember passing out from exhaustion. Braving the dangerous conditions, Midgett and his crew made several trips back and forth, rescuing a total of 42 survivors.

Today, the history of the Outer Banks’ Life-Saving Service lives on with the Coast Guard men and women at Stations Oregon Inlet and Hatteras Inlet. They stand the watch over the Graveyard of the Atlantic, continuing the legacy of maritime rescue.

On Sept. 16, 2017, crewmembers at Station Oregon Inlet received a report that a 50-foot charter vessel carrying five people capsized in a fierce storm. The boat crew quickly launched their 47-foot Motor Life Boat and headed out into the turbulent seas.

Once they arrived, they found the five mariners near their capsized boat in heavy seas. Navigating to the capsized boat between shoals and surf, the Coast Guard crew rescued the mariners and brought them back to the station.

“What’s notable wasn’t just the stormy conditions, but the crew’s inexperience,” said Master Chief Petty Officer Mark Dilenge, officer-in-charge at Station Oregon Inlet. “Our coxswain had only qualified for heavy weather a few months before, and the rest of the crew were young members. Together, however, they were able to respond and pull all five mariners from the water in under four minutes.”

The Graveyard of the Atlantic remains a hazardous environment for mariners, especially in foul weather. However, Coast Guard men and women stand the watch, just as the crews before them did.

“I can say nothing other than ‘wow’ when thinking on the history in this area,” said Dilenge. “Our service is interwoven into the country’s beginning at every pivotal point, and that is reflected very strongly here in the Outer Banks.”