Dry Ice Test Prelude to Restoring Lighthouse

As the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse approaches its 150th anniversary guarding the Outer Banks coast, its caretakers are exploring 21st century ways to maintain the tower’s distinctive candy-stripe markings, the first step in preparations for an upcoming comprehensive restoration of the National Historic Landmark.

Patches of paint were blasted off the exterior by a dry ice “gun” during a recent test to apprise how well it would strip off multiple layers of red paint on the lighthouse’s octagonal base, and the black and white on its famed swirled bands.

Blast cleaning with compressed air and dry ice pellets is considered less destructive and cleaner than older methods such as sand blasting, which is why it’s better for historic structures like the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the nation’s tallest — and arguably most famous — brick lighthouse.“We are looking at using the most technologically advanced methods,” Cape Hatteras National Seashore Superintendent Dave Hallac said to a small gathering of local media on Oct. 29 at the lighthouse site.

If the environmentally friendly technique proves effective in stripping the paint, the long-overdue overhaul of the cherished icon will be able to start with a fresh façade.

A new paint job on a clean surface serves more than makeup on a pretty face, it’s addressing the unintended consequence of layers of paint.

Hallac said that it appears that years of coating the brick lighthouse has created an impermeable layer that traps moisture inside and between its double walls, subjecting the interior’s cast iron, steel and wood structural elements to corrosion, mold, mildew and rot.

“This restoration project is going to remove all the paint inside and outside the lighthouse,” the superintendent said. “Once the paint is removed, it will be recoated with some kind of breathable paint.”

Meanwhile, Hallac said, monitors have been installed at different spots in the lighthouse to measure moisture, which will help determine locations of troublesome leaks, drips and condensation.

There’s a total of 11,800 square feet of painted surface on the outside of the 1870 lighthouse, Hallac said, and 5,700 square feet inside.

The goal is to protect the brick substrate, said Rick Dupuy, president of HydroPrep, the Newport News, Virginia, contractor doing the test. Rather than abrading the surface, strikes from the carbon dioxide pellets release kinetic energy that lifts the coating. The frozen pellets evaporate harmlessly.

“Choosing the right surface prep is the key,” he said.

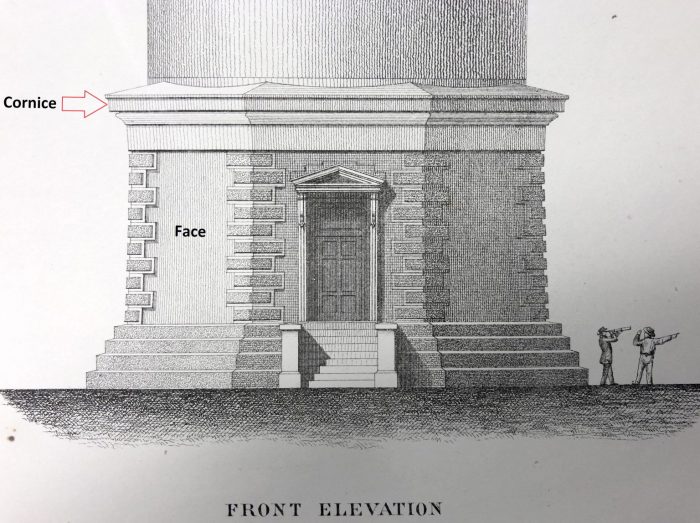

As Dupuy explained the technique, blast gun operator Sy Emilerins, standing on a lift platform about 20 feet from the ground, directed the high-pressure air and dry ice at a 4-foot-by-4-foot section on the face of the lighthouse base, pounding away at the layers of red paint just under the lighthouse’s granite cornice. As Emilerins worked, white clouds created by the carbon dioxide gas hovered spectrally above the newly stripped patch.

“You can see it’s pretty benign,” Dupuy said, noting that the method uses no chemical solvents or abrasive material and creates little debris. “There’s nothing on the ground.”

Strolling over to where Emilerins was stripping a square from a white stripe, Dupuy picked up a blistered paint chip that exposed the different layers.

After grabbing a fistful of pellets from large blue box called a tote, Dupuy held out his gloved hand to show the pellets. Surprisingly, they did not feel particularly cold when touched quickly – although longer contact might freeze-dry a finger or two.

Some form of dry ice blasting has been around since the Navy started experimenting with it in the 1940s. In addition to historic preservation, modern uses of dry ice blasting include sanitizing, decontamination and mold removal.

One early version of the technology was developed at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, according to a March 1997 press release from the laboratory announcing that the “cryogenic pellet accelerator” was a safer, cleaner and more efficient way to strip paint. The technique had originally been used by the laboratory to fuel experiments with fusion, the reactive energy that powers the sun.

HydroPrep has used the process in other historic preservation projects, Dupuy said, including recent restoration work on the flagpoles at Arlington National Cemetery.

The contractor will also examine and assess the condition of the bricks, Dupuy said. If the agency likes what it sees, he said he plans to bid on the project.

Between costs for equipment mobilization, materials and labor, the paint removal test cost is expected to total $5,000 to $6,000, said Robin Snyder, National Park Service Outer Banks Group acting deputy superintendent. Estimates were not available for removal and repainting costs.

Originally red and white

According to the park service’s online information about the Cape Hatteras Light Station, the 198.5-foot-tall brick lighthouse was initially painted red on top and white on the bottom. In 1873, it received its famous black-and-white-striped daymark, the unique pattern assigned to each lighthouse. The tower was repainted in 1994, 2002 and 2014.

But John M. Havel, a Cape Hatteras lighthouse researcher with Havel Research Associates in Salvo, who was at the site watching the paint removal test, said that he also recalls seeing photographs of the tower being sandblasted “from the top down” in spring 1976 in preparation for repainting.

“So, at that time they were not that concerned,” he said about sandblasting.

Havel, a retired graphic designer for the Environmental Protection Agency and current board member of the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society, has done extensive research on the historic structure and design features of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

In a 2019 interview, Havel noted that the Cape Hatteras lighthouse has had only one major preservation, which was done by contractor International Chimney about seven years before the lighthouse was moved from the eroding beach in 1999 by the same contractor. In his research, Havel said, he discovered that the lighthouse originally had a Victorian-style black iron fence, with decorative spearheads, around its base to keep out livestock.

The park service is currently working with contractor Quinn Evans in Washington, D.C., on the design phase of the restoration project, Hallac told reporters. The park service is considering including a replica of the fence made of a more durable, nonmetal material. The agency will also look at restoring native grasses in the landscape and improving the “pattern” for visitors to explore the lighthouse station site, which includes two keepers’ buildings.

Design discussion, Hallac added, includes replacing the current rotating incandescent light system at the top of the lighthouse with some version of the original Fresnel lens – whether to repair the original or replicate it with an acrylic lens. Another major consideration is how to best address repair and replacement of ironwork and window frames.

“We’re still trying to figure that out,” the superintendent said. “It’s that balance between preserving some of that historic fabric.”

A total of $18,727,000 for Cape Hatteras Lighthouse repair was included in the agency’s fiscal 2020 “budget justifications” document.

“One thing to recognize is there are a lot of pieces that have been replaced over time.”— Dave Hallac, Superintendent, Cape Hatteras National Seashore

In a later interview, Hallac said that the final restoration design will ultimately come down to a “value analysis” that weighs historic integrity, budget and environmental conditions.

“One thing to recognize is there are a lot of pieces that have been replaced over time,” he said. “This really is an extraordinarily challenging environment.”

To his point, during its century and a half of existence — much of it perched at the edge of the ocean — the lighthouse has been pummeled by storms, undermined by surging waves and marinated in salt spray. Piecemeal repairs have been made through the years on corroded metal and rotted wood. In 2001, for example, just two years after the lighthouse was moved, a 3½-inch chunk of cast iron from a bracket bracing the spiral staircase fell from the second landing, reportedly nearly hitting a woman in the head. Repairs to the staircase cost more than $500,000.

When possible, Hallac said, in the interest of resiliency, durability and cost, it may make the most sense to use modern materials that can withstand the harsh coastal conditions.

“We’re looking to zero in on the best balance between preserving the historic architecture of the structure” and protecting it for the future, he said of the restoration. “That salt air is forever present and constantly waiting to oxidize metal surfaces.”