Fighting the demons: Owen’s odyssey

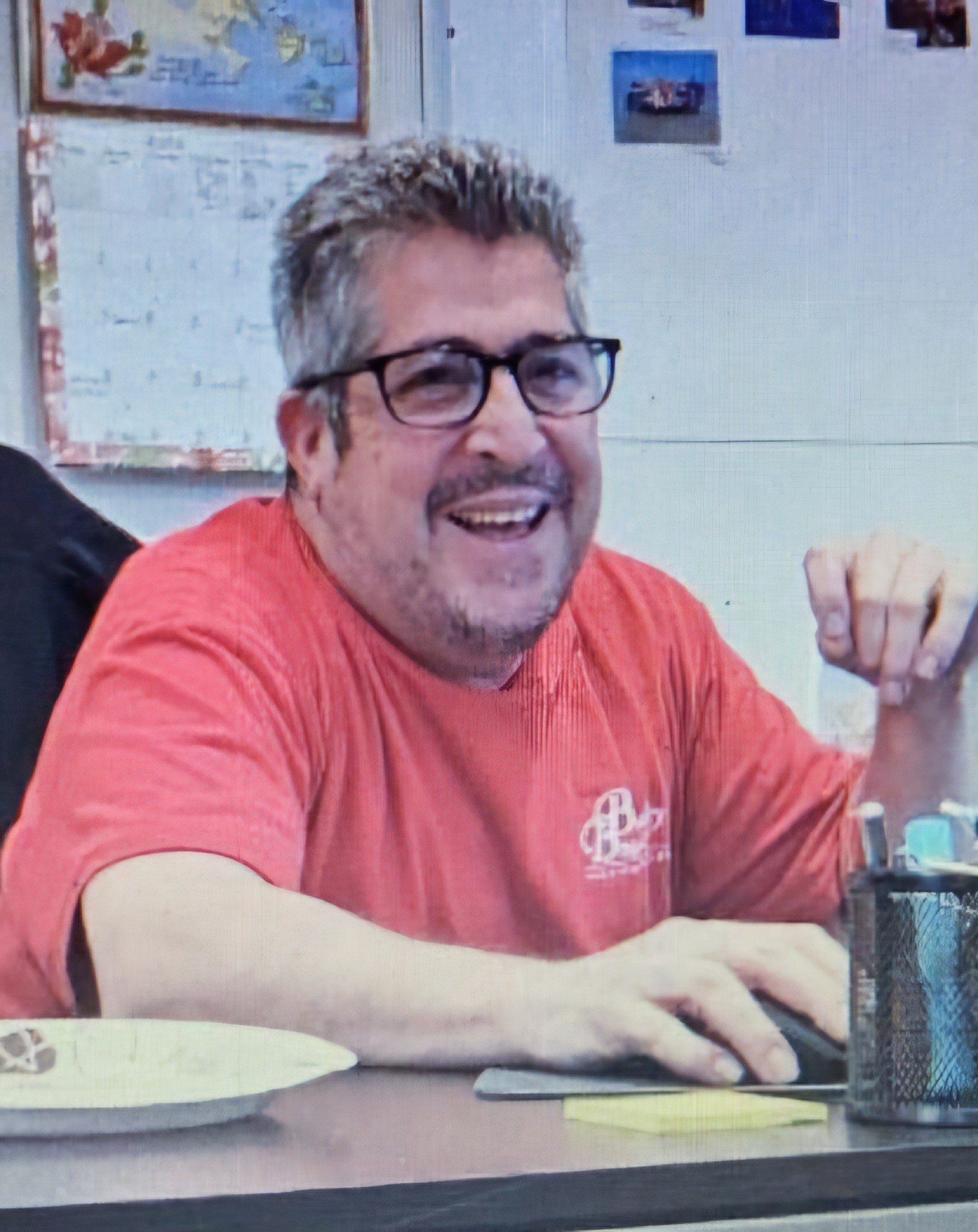

Owen Saunders is the hard-luck young man that you like rooting for. Just as hard as Owen roots for his nine-year-old son, Gauge, when he smacks a baseball toward the left field fence at the Walker Park baseball diamond in Wanchese.

Owen celebrated one year of being drug free on Aug. 2, and Gauge will celebrate a two-year anniversary of reuniting with his dad in September. Both of their successes are largely due to the other.

“My son is the largest motivating factor in staying sober and changing my life,” Owen, now nearly 31, asserts.

“My dad comes to all of my games, lets me help out at his work,” Gauge says with obvious glee. “He’s really cool. I never want to disappoint him, but I do sometimes do.”

On a late spring afternoon, Owen shows up to an interview in multi-pastel colored shorts, a dark T-shirt with an Under Armor logo on the front, Crock shoes and a white sweat band around his head partially hiding a thatch of light brown hair. He’s skinny and walks with a sort of loose, crooked gait. His face is shallow, which makes his deep-set eyes all the more startling. There’s kind of a Huck Finn charm about him.

These days, Owen helps coach his son’s sports teams and goes back to play in an alumni basketball game for a local church. He’s a fry cook at Sam and Omie’s, a popular restaurant in South Nags Head.

Some of the people living in the community where Owen grew up – and where he did his fair share of damage – say he’s a likeable chap. “Owen Saunders could be the sweetest person you’ll ever meet,” says Kamela Warren, a lifelong Wanchese resident.

Until recently, people hadn’t seen much of that Owen Saunders, not his family, his friends, not the cops, not his son, not even Owen himself. It was as if the Owen Saunders that everyone is rooting for disappeared. For more than 14 years.

THE ROAD TO ADDICTION

Fishing, scalloping, shrimping, crabbing. It’s a rite of passage for young men in Wanchese. For Owen, that transition came earlier than for most boys his age. In the summer after finishing the eighth grade, Owen hopped aboard his grandfather’s shrimp boat. Out on Sunday; back on Friday. The $2,500 a week pay was an elixir for a boy of 15.

Owen never returned to start the ninth grade. It turned bad quite innocently enough. Kidney stones. He went to a urologist and got Vicodin. Then Percocet. Owen saw a family doctor in Wanchese. “He kept prescribing the pills for me. I started out with a prescription of thirty a month. After two years, I was up to 150 of them a month, and I was running out of them two weeks in.”

By age 18, Owen had moved out of the house he shared with his mother and a stepsister. He got a girlfriend. He had money. He had his prescriptions. Life seemed good.

Owen started working on his uncle’s scallop boat out of Wanchese. They were on the water for more than two weeks straight dredging for scallops. “We’d shuck scallops day and night, sometimes for forty-eight straight hours with little sleep or little to eat. We were young then, the crew.”

But not young enough to avoid the Grip. That’s what shuckers and fishermen call it when their hands get swollen and the fingers are frozen into position from repetitive movement. Medical professionals call it carpal tunnel syndrome. Regardless, it proved one more source of pain for Owen. And one more reason to get more pills to kill that pain.

Still, Owen soon was pulling down $250,000 a year, living in a fancy house, driving three vehicles. “I had it all. I had the life,” he says.

And Owen’s good fortune, such as it was, soon ran out.

The opioid pills that doctors seemed all too willing to prescribe for him came to a screeching halt. “I was doctor shopping, trying not to run out of pills.” Then the doctors got wise to him. “They cut me off. I couldn’t get no pills.”

Not the legal way. Owen bought pills on the street. Lots of them. But that came with a high price – money (up to $40 a pill) and addiction.

At one point, Owen found a drug bonanza. He met a guy who was bringing back a seemingly inexhaustible supply of Methadone from a clinic outside Dare County.

“I was buyin’ about 300 pills a month,” he recalls. “Me and my girlfriend, we’d wake up in the morning, grab a handful of 15 or 20 pills from a bowl on the nightstand and gobble them down. That’s how we started our day.”

Then a childhood friend of his introduced him to the drug that became his choice.

“My friend, he was an intravenous heroin user. I was afraid of needles at first, so I just snorted it. It wasn’t but about six months until I was injecting heroin. First time I injected, it was incredible, it was better than sex. I realize now it wasn’t good, but then it was the best thing in the world. It was all I thought about. I’d go days and days chasin’ heroin. I ain’t gonna lie to ya, man, I still think about that high.

“There wasn’t nothin’ I wouldn’t steal, nothin’ I wouldn’t do to get money for drugs, like breakin’ into people’s houses, hittin’ up my friends for money.”

Owen started losing more than his morality. He lost his house, his cars and, most importantly, his son. It was 2009. Owen was 24; Gauge was 2 years old and went to live with his maternal grandparents for the next six years.

Then Owen started getting arrested.

“Yeah, I knew Owen Saunders,” says Kevin Duprey, head of the Dare County Narcotics Task Force. “He and his buddies would steal anything that wasn’t nailed own. They were always doing drugs. They nearly destroyed the community.”

A HALTING PATH TO RECOVER

Owen got his first referral to New Horizons, Dare County’s only substance abuse and mental health treatment center, in 2010. His recovery didn’t stick. “I wasn’t ready,” he shrugs.

In 2012, Owen did a little more than four months in jail on a breaking and entering charge. He was released and out for about three months before getting busted for possessing heroin. He served almost five months. After his release, he went back to what was most familiar, other than using drugs: fishing. This time in South Carolina.

He returned to Wanchese just short of Christmas. “Dec. 19, 2012. I remember it like it was yesterday. When I got home, I discovered I had missed the court date. I knew I was in trouble. But bein’ it was almost Christmas, and I wanted to spend the holiday with my boy, who was about 4 years old. After the holidays, I was going to turn myself in.”

The cops weren’t into the seasonal spirit. They arrested Owen and he served another four months.

After serving jail time again, there was one more odyssey left in Owen. He traveled with a churchgoing friend and fellow fisherman, fishing out of Port Judith, R.I. The friends eventually had a falling out after a senseless argument, and Owen returned to Wanchese again.

And he came back to New Horizons.

But, despite a probation that left two years hanging over his head, there was a search for one last high. He was an addict not quite ready to embrace sobriety.

It was a case of guilty, but mostly stupid. “I was goin’ to buy some cocaine. I was walkin’ toward the dealer and I was textin’ him, only I texted my probation officer by mistake.” The probation officer reported him for violating his probation. He was lucky. “I did 48 hours. They call it a Quick Dip. It’s like a warning on your probation. Do anything else again and you’re doing the time.”

This time, he was ordered back to New Horizons and into an intensive outpatient program, treatment and recovery’s version of hard time for hard addicts.

“At first, I thought it was stupid, I just wanted to go to work and maintain my sobriety by keepin’ busy. I wanted them to just give me the Suboxone [a drug used to help addicts to withdraw from opioid addiction while in recovery] and leave me alone. But after a few weeks, I started liking it. I got into the group sessions. I got new sober friends out of the groups.

“The people at New Horizons have been very good to me.” He adds, “I wouldn’t be where I am now if it wasn’t for these people. Hell, I’d most likely be dead. Thank God, it’s over.” Owen offers that 90 percent of his friends and family members who did drugs are now sober.

Things got even better when Gauge moved back in with him. They live in a rented trailer in Wanchese. “He’s a spittin’ image of me, man. He does great at sports. I want him to go to college, and make somethin’ of himself.”

In a way, Owen and Gauge are helping each other to make something of themselves. “I want to be here for him. It’s my motivation to stay sober.”

“It’s been awesome having my dad back,” Gauge says.

Sherri Jenkins, Owen’s counselor at PORT/New Horizons, says Owen’s turnaround has been nothing short of amazing. “He’s working very hard at his recovery and making positive changes in his life, like raising his son, looking out for his younger sister and working full-time. Owen has such an infectious personality that everyone here adores him.”

Owen constantly checks a sobriety app on his cell phone, a convenient reminder of his progress. “Three hundred and twelve days sober,” he says with a mixture of pride and disbelief. “I can’t wait to say, that I’ve been sober for one year. What a feelin’ that’ll be.”

Owen will be an addict in recovery the rest of his life. Gauge has the rest of his life ahead of him. It’s hard not to root for both of them.

(This is the fourth part in a series being published by the Outer Banks Sentinel that examines drug abuse and narcotics trafficking in Dare County, the people committed to fighting and treating it, and those who become its victims. The first part was published on Aug. 3, and the series will run until Aug. 31.To read more in the series, go to http://www.obsentinel.com/drug_war/)