Searching for the Lost Colony on Hatteras Island

Artifacts found in recent digs in Buxton may be solid evidence that the so-called “Lost Colony” fled to Croatoan. Or they may not.

Until findings are published, the work is among numerous unproven tidbits that add to centuries of speculation on what happened to the English settlers who disappeared from Roanoke Island after 1587. The fate of the 117 men, women and children remains the oldest mystery of colonial American history.

In a presentation in Manteo last month, archaeologist Mark Horton announced that artifacts unearthed while working with a team of volunteers from the nonprofit Croatoan Archaeological Society on Hatteras Island reveal ongoing contact between Europeans and Indians, including with people from the 1584-1587 Roanoke Voyages and the1607 Jamestown settlement.

“What we found out is there is definitely a period of assimilation going on,” said Scott Dawson, the president and co-founder of CAS.

The only clue the vanished colony left behind was “CRO” carved on a tree and “CROATOAN” carved on palisade post. No documented evidence so far has been found showing that all, or even some colonists, did indeed escape to Croatoan.

But Dawson said that Horton, a professor of archaeology at the University of Bristol whose expertise is contact archaeology, is convinced that the CAS team has found evidence that shows colonists not only went to Croatoan – today’s Buxton – they stayed and blended with the Indian community.

Horton, who has returned to England, did not respond to a request for an interview. However, Dawson talked about the work the University of Bristol team is doing with Hatteras islanders.

“What we have is pretty awesome,” Dawson said. “We definitely have 1585. Most likely we have 1587.”

A Nuremberg token found during a dig last year near postholes of what had been a native longhouse was one of the more telling finds, Dawson said, because it was dug from a soil layer indicative of the 16th century. It matches three other tokens found earlier at Fort Raleigh and another found in the 1930s on Hatteras Island.

The token was found near smelted copper, metallic stoneware and a fire bar.

“So all of that is just screaming ‘metallurgy’,” he said

Evidence of 16th-century metallurgy was found years ago under an earthen mound at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site on Roanoke Island, where historians had once believed the English had built a fort or the colonists had built their settlement. But no direct evidence of either has yet to be documented anywhere on Roanoke Island.

Other findings at the Hatteras digs include a watch fob and a small silver alloy ring. A gold-laden rapier handle points strongly at English presence, rather than simply trade goods.

“You don’t trade a rapier,” Dawson said, adding it would have been owned by a gentleman. “There’s no need to trade something so valuable.”

That, along with a piece of a writing slate, he said, would most likely have come from a member of the 1587 colony.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a slam-dunk-Lost Colony. Done. Found,” Dawson said. “There’s always that crazy remote possibility of an unknown pirate that washed up.”

Historians know that the English traded copper with the Indians in exchange for food and supplies. Records show that some English soldiers had stopped in Hatteras in 1584 and 1585, but there is no account of visits from the 1587 colonists.

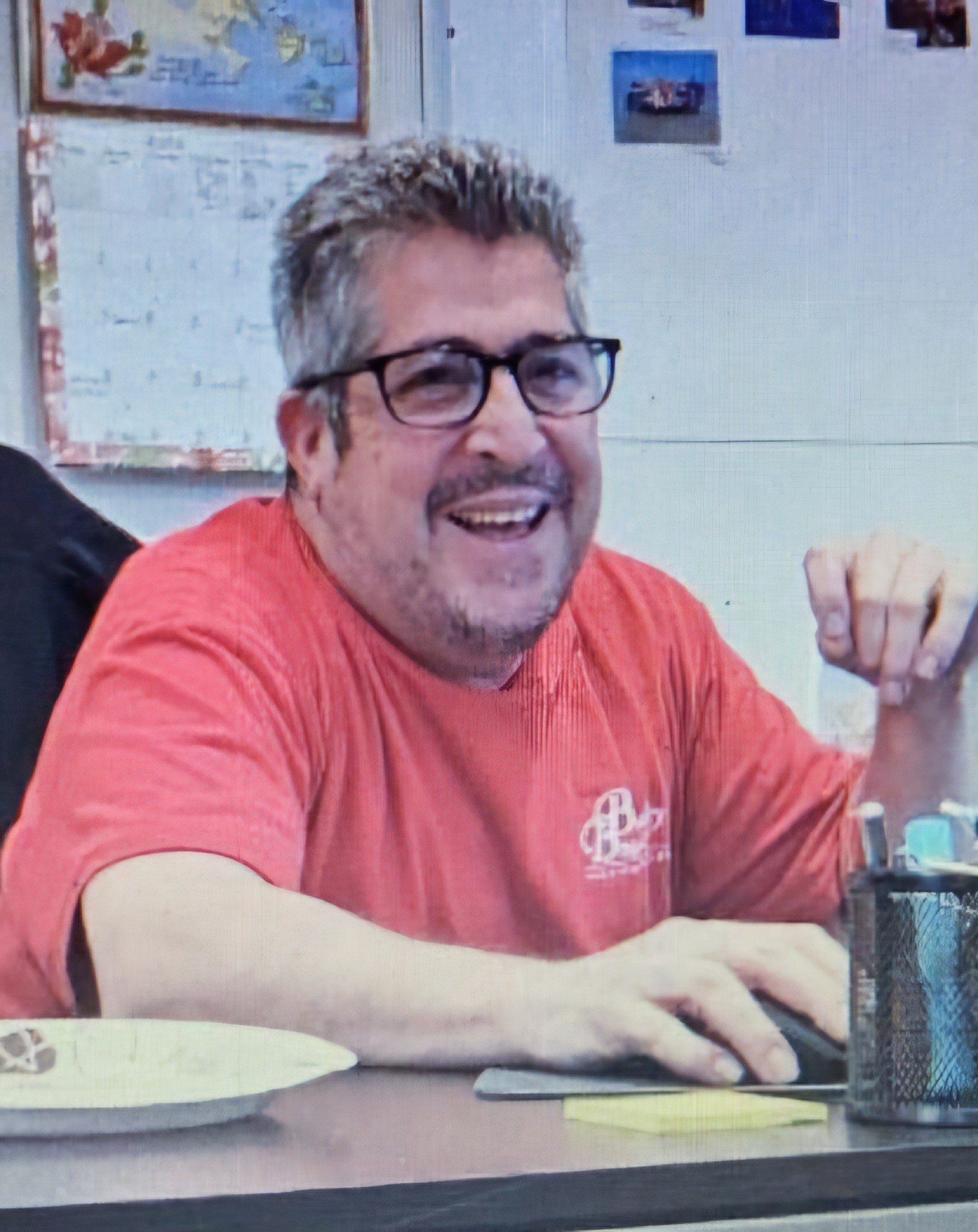

Dawson, 36, said his passion for the project stems from his determination to learn about the Croatan Indians – who were instrumental in helping the colonists – and to give them the credit in American history that they deserve. As an island native, Dawson said his family’s roots go back to the Croatan, a branch of the Algonkian.

A social studies teacher in Elizabeth City, Dawson said he is raising funds for continued excavations of the site. He said he and his wife, Maggie, who co-founded CAS in 2009, have curated some of the important artifacts. The couple and CAS volunteers are in the process of cataloguing the thousands of artifacts, including shells, arrow heads, and pottery pieces. Meanwhile, he said that Horton is compiling his report and writing a book on the digs.

“It’s going to be an amazing publication,” he said, “and I think it’s going to be something that Hatteras Island will cherish.”

Although the group has conducted digs for the past seven years, Dawson said, it wasn’t until 2012, when they moved a mile north, that it began finding “some fantastic stuff” located on private property about one or two lots away from where veteran East Carolina University archaeologist David Phelps had explored in the 1990s.

During several digs, Phelps, renowned for his work at early Native American villages in northeastern North Carolina, had determined the half-mile site on a high ridge in Buxton Woods stretching to the village was the location of the ancient capital of the Croatan chiefdom – the birthplace of Manteo, the Indian who assisted the 1587 “lost” colonists.

The Croatan were the only Native American society that lived permanently on the Outer Banks.

Excavations done by Phelps’ team turned up a workshop area, a 16th-century gunlock, and, most significantly, a 16th-century gold signet ring that was later traced to an English nobleman. At the time, the finds were deemed the first notable link between native Indians and English explorers and possibly even the Lost Colony.

According to Charles Ewen, the director of ECU’s Phelps Archaeology Laboratory, the site – also known as Cape Creek – was first recorded in 1938 by Joffre Coe, an anthropology professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. In 1954, William Haag, an archaeologist with Louisiana State University, surveyed the barrier islands and declared that Cape Creek had “the best midden found on the Outer Banks,” Ewen said.

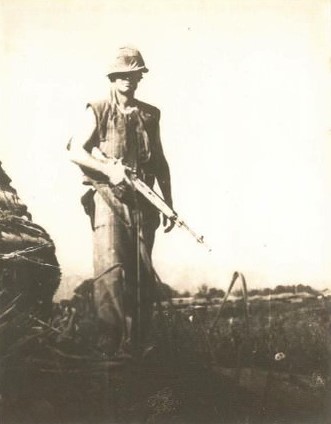

When Hurricane Emily in 1993 exposed the midden – or household debris – at the site, Phelps came to investigate. Over the course of multiple digs, Phelps unearthed thousands of artifacts, including bone jewelry, shell fragments, pieces of munitions and coins and pipes.

Unfortunately, Ewen said, Phelps never wrote reports on the digs or catalogued or curated many of the items, and many unopened boxes of artifacts and paperwork from Phelps’ work remain at ECU.

Although Phelps, who died in 2009 at age 79, was recognized for his brilliance as an archaeologist during his 30-year career, his failing was not documenting his work. In 63 volumes of North Carolina Archaeology reports from 1949 to 2014 published by UNC-Chapel Hill, no mention was found of Croatoan, Hatteras Island or David Phelps.

Without published reports on field work, projects lose relevance to the findings and bear little credibility to professionals and academics.

Finding the gold ring at Croatoan earned Phelps the most media attention, but Ewen said his work at Tuscarora Indian sites at Neoheroka in Greene County and at Jordan’s Landing in Bertie County were also significant.

To this day, the gold ring is still considered an important link to the first English explorers in America, and their contact with the native population. But it was later determined to have been in a layer of 17th-century dirt, meaning it was likely a trade item.

Ewen said that another nonprofit group, the Lost Colony Research Group, has also been doing archaeology on Hatteras Island, but they do not work with Dawson’s group.

“We work very quietly,” said Anne Poole, one of the group’s founders. “We work behind the scenes.”

Poole said that there are currently two active archaeology projects, and several DNA projects, that are being pursued.

“We have some promising leads with people who may be living descendants of the Lost Colony,” she said. The group has also embarked on a “very, very special project” with a national museum. “There’s something potentially pretty hot there that we’re working on,” Poole said.

Poole’s partner, Roberta Estes, is a genetic genealogy professional.

In the near future, Poole said, the group is hoping to partner with Ewen on a Hatteras Island dig.

Another nonprofit group, the First Colony Foundation, a group of veteran archaeologists that has partnered with the National Park Service, is currently exploring Lost Colony leads in Fort Raleigh and at a promising site in Bertie County.

Ewen, who is working on a book of all the published theories on what happened to the Lost Colony, is holding his judgment on whether the CAS digs found a link to the Lost Colony.

“We don’t have really incontrovertible evidence that it is,” he said. “I’m being conservative. I think the profession will look at that with a skeptical eye . . . until we see it in print.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

For more information on the Croatoan Archaeological Society, visit Dig Hatteras on Facebook or go to the website, http://www.cashatteras.com/. Send donations to: Croatoan Archaeological Society, Box 938, Buxton, NC 27920 .