Historians at OBX event reveal enigmatic Thomas Harriot

In July 1587, the English ship Lyon put ashore on Roanoke Island with 118 men, women and children.

The attempt to establish an English colony in the New World was the culmination of Sir Walter Raleigh’s investment in exploiting lands he had been granted by Queen Elizabeth I.

Hoping to be met by the 15 men Capt. Ralph Lane had left to hold the island for the colonists’ arrival, they instead found only the sun-bleached bones of one of the soldiers.

Nonetheless, they remained and began the work of repairing the fort and building a town. After a month, though, it was apparent that without more supplies and additional colonists, Raleigh’s investment in the New World would not succeed, and Governor John White returned to England, hoping to secure the supplies and people needed to strengthen England’s toehold in the New World. But a proxy war that was being waged with Spain became open warfare and the Spanish Armada intervened. White was not able to return to Roanoke until 1590.

When he arrived, there were no colonists, the only clue to their fate was the word “CROATAN” carved in a tree. It may have been an indication that the colonists had relocated to Hatteras Island, but the loss of the rescue expedition’s captain, a hurricane and a near-mutinous crew sent the relief ships back to England before they could explore Hatteras Island.

What is now called the “Lost Colony,” might have the appearance of a desperate, almost unplanned attempt by England to colonize the Americas, but it was instead the product of a carefully planned investigation of an uncharted, unknown new land.

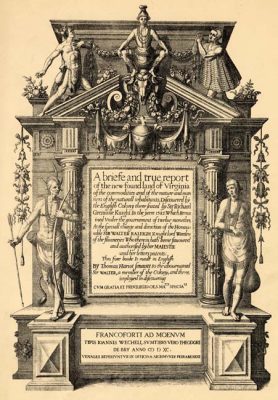

At the center of that investigative work was Thomas Harriot, a scientist and mathematician whose “A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia,” was the most complete description of that first attempt by the English to understand the New World.

The recent “OBX History Weekend: Searchers of the New Horizons” was a three-day, in-depth look at some of the most significant events and people who shaped the history of the area. Produced by the First Colony Foundation, Elizabeth R and Co. and the National Park Service, an entire day was devoted to exploring the life and times of Thomas Harriot.

The recent “OBX History Weekend: Searchers of the New Horizons” was a three-day, in-depth look at some of the most significant events and people who shaped the history of the area. Produced by the First Colony Foundation, Elizabeth R and Co. and the National Park Service, an entire day was devoted to exploring the life and times of Thomas Harriot.

What emerged from the lectures was a portrait of a remarkable man — a mathematician who was dabbling in algebraic equations at a time they were little known in Europe.

He was a linguist whose work presaged a 19th century syllabary alphabet, an astronomer, and chemist. Although in 16th century England, Harriot’s work combining various materials was called alchemy.

Yet for all his intellectual accomplishments, Harriot’s only published works were his depictions of the English experience in the New World, which may be why he is not better known today.

Dr. Robyn Arianrhod, speaking during the symposium from her native Australia, is the author of, “Thomas Harriot: A Life in Science,” a book that explores Harriot the scientist.

She introduced him to the audience, outlining why so little is known about Harriot.

“He is nothing if not enigmatic. Without really knowing where he was born, or who his parents were, although we do know they were working people, not gentry,” she said. “To add to the mystery, we only know about him because some 8,000 pages of his research notes were found hidden away in an old castle 150 years after he died.”

He was a man who was, in many ways, ahead of his time. A hundred years before Newton, Arianrhod said, Harriot was experimenting with prisms and the diffusion of light. He was also the first mathematician, she noted, to work entirely in mathematical formula.

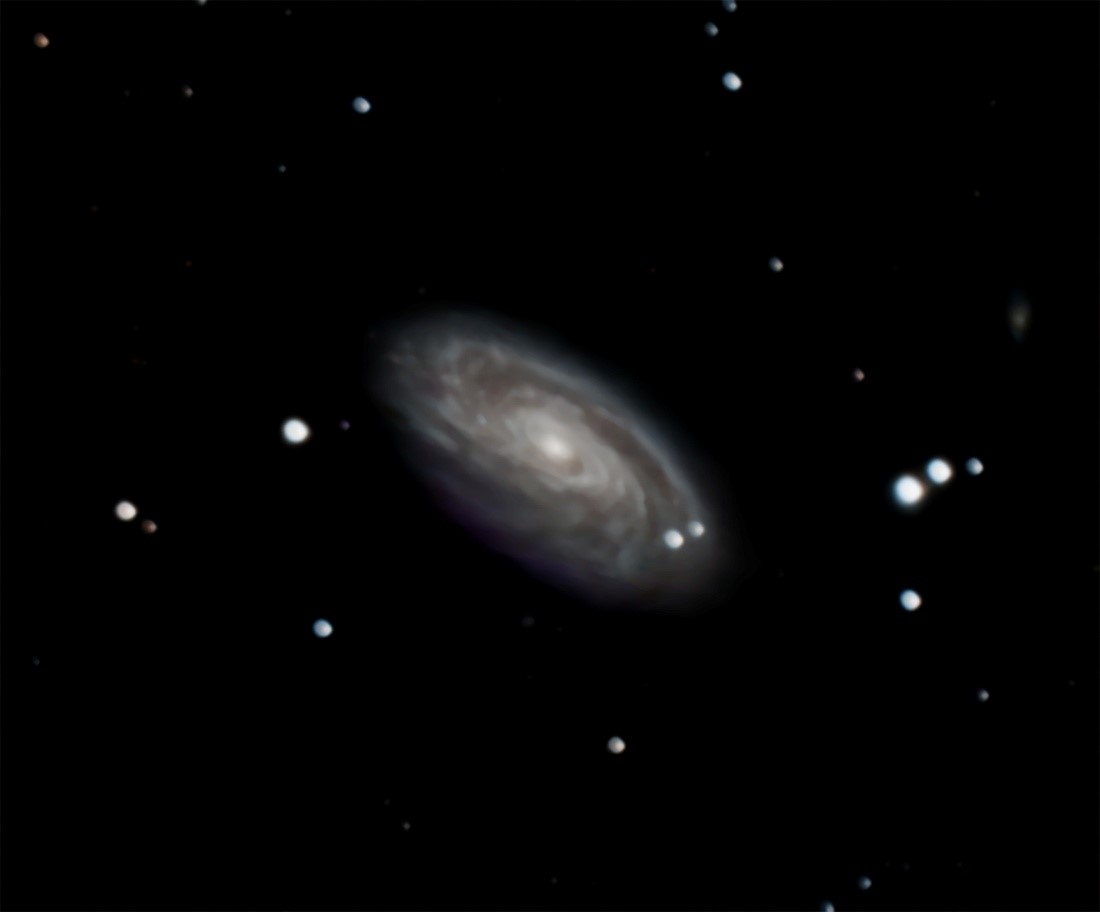

Astronomy fascinated him and when telescopes became available at the beginning of the 17th century, Harriot was one of the first to understand the scientific potential of the new instrument.

“Harriot was the first to leave a surviving record of a telescopic astronomical observation,” Arianrhod said. “It was a rough outline … sketch of the crescent moon. But it was the very beginning of the new era of telescopic astronomy,

The sketch dated July 26, 1609, was “… Apparently a few months before Galileo began doing the same thing,” she added.

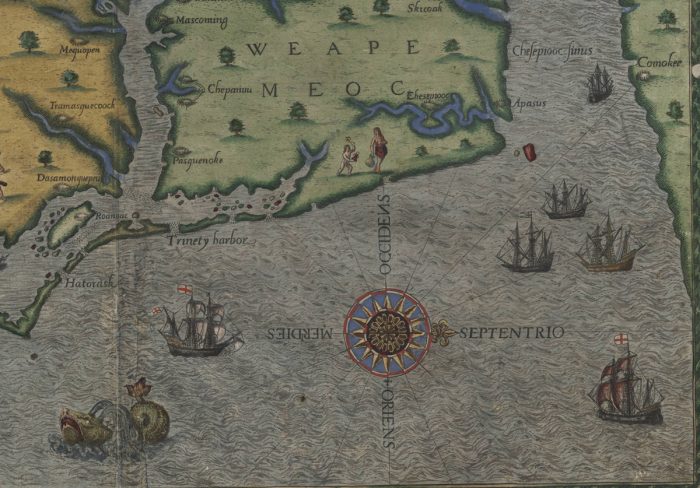

But it is his descriptions of the New World that Harriot is best known. His “A briefe and true report of the new found land of Virginia” was originally published in Latin in 1588. In 1590, publisher Theodor de Bry translated the Harriot’s work into four languages and included copperplate reproductions of John White’s depictions of the New World, making it an early international bestseller.

He was in the New World because of his relationship with Raleigh, and it was probably his mathematical skills that brought him to Raleigh’s attention.

Raleigh had been granted the right to colonize the New World in 1584. An experienced sailor, he knew that a journey of 3,500 to 4,000 miles across the ocean would require new ways of thinking about navigation.

“Raleigh wanted his captains and navigators to be the best trained in the world,” Arianrhod said.

At that time, ocean navigation used the sun and stars to determine position, and Harriot, with his interest in astronomy and math, was the ideal person to create a more precise way to navigate.

But Harriot was much more than an armchair scientist. When Raleigh sent his first expedition to Roanoke Island in 1585, Harriot was a part of it and what he observed has become a remarkable eyewitness account.

How he saw the people of the Roanoke area and how he described them was influenced, said Dr. Robert Fox, Emeritus Professor of the History of Science at Oxford, by his days as a university student. It was a time of dynamic intellectual challenge and Harriot, who attended the Oxford from 1580-83, was in the middle of it.

“These new students were receptive to the tide of Renaissance humanism that was beginning to circulate in Oxford,” Fox said during the event. “And I think that tide of humanism had its long-term consequences for Harriot.”

Fox noted the way Harriot writes about the Algonquin people of the area as evidence of his education in humanism. His description of Native Americans departs significantly from the view of the time that they were simple savages.

“What he saw was a settled society, codified social structure, a simple legal system, hierarchy of gods headed by a single god. There was even some notion of an afterlife. And for Harriet, Algonquin religion has all the character, I think, of a pristine faith, perhaps the face of a prelapsarian world,” he said. “It was a world — I’m thinking back again to his Oxford experiences — free from the confessional tensions that he had known and witnessed in Elizabethan England.”

Perhaps more than anyone else on the 1585 expedition, Harriot had the best understanding of the culture and politics of native peoples.

A first reconnaissance mission led by Capt. Philip Amadas and Master Arthur Barlowe returned to England in 1584 with two Native Americans named Manteo and Wanchese.

They were housed at Raleigh’s London residence, Durham House, and while there Manteo worked with Harriot to learn each other’s language. From that, Harriot devised a syllabary — a sound-based alphabet — more than 200 years before the same technique was successfully developed by Sequoyah of the Cherokee Nation in the late 1810s.

“Manteo and Harriot collaborated to produce one of the most remarkable achievements in 16th century science. Harriot called it a new way of recording language by sound, rather than by meaning. Harriot called it, ‘an universal alphabet containing six and 30 letters whereby maybe expressed the lively image of man’s voice in what language soever …’” said Dr. Karen Kupperman, Silver Professor of History Emerita at New York University, during her History Weekend presentation.

Harriot understood that the society he was seeing was not some pure form of humanity that existed before the Biblical fall of mankind, that even if there were not the religious tensions of Catholic and Protestant religions of England, there was still conflict. While he was there, a war was being waged between the villages and Roanoke Island that comprised King Wingina’s kingdom, and he wrote about that.

“Their maner of warres amongst themselues is either by sudden surprising one an other most commonly about the dawning of the day, or moone light; or els by ambushes, or some suttle devises …” he wrote.

But as he looked at their cultures realistically, he also applied that standard in describing the actions of the English, and his mention of the violence against Native Americans may have presaged the failure of the Lost Colony, when the tribal nations of the region turned against them because of death of King Wingina at the hands of the English.

“And although some of our companie towardes the ende of the yeare, shewed themselues too fierce, in slaying some of the people, in some towns vpõ (upon) causes that on our part, might easily enough haue been borne withal …” he wrote.