Island History: The 137-year anniversary of the wreck of the Schooner Ada F. Whitney

The wreck of the schooner Ada F. Whitney, which occurred on September 22, 1885, was a very difficult but somewhat routine event for the life-savers during a somewhat difficult time in America.

In the year of this wreck, 1885, America had 38 states – yet to become would be the states of Washington, Idaho, Montana, the two Dakotas, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Oklahoma, as well as the obviously missing Alaska and Hawaii. Our population was a tad over fifty million. We had two U.S. Presidents that year: when Chester A. Arthur died in office, VP Grover Cleveland became President. An economic depression had started in 1882, being a gradual development rather than a sudden crash, and was waning to a conclusion in 1885. Notable events that year included two now American icons: the dedication of the Washington Monument, and the arrival of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor from France. Somewhat less significant, but notable, were Mark Twain’s publishing of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the U.S. Patent given to the soft drink “Dr. Pepper.”

In the year of this wreck, 1885, America had 38 states – yet to become would be the states of Washington, Idaho, Montana, the two Dakotas, Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Oklahoma, as well as the obviously missing Alaska and Hawaii. Our population was a tad over fifty million. We had two U.S. Presidents that year: when Chester A. Arthur died in office, VP Grover Cleveland became President. An economic depression had started in 1882, being a gradual development rather than a sudden crash, and was waning to a conclusion in 1885. Notable events that year included two now American icons: the dedication of the Washington Monument, and the arrival of the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor from France. Somewhat less significant, but notable, were Mark Twain’s publishing of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the U.S. Patent given to the soft drink “Dr. Pepper.”

Commerce was dominated by the U.S. East Coast. Domestically, the coastal Atlantic was then akin to our I-95: almost all traffic north/south was here. Five of the top U.S. cities were on the Atlantic coast: New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn (a separate city then), Boston, and Baltimore, the latter being our ship-building capital. And almost all of this trade was carried by a specific type of sailing ship: the schooner. It was the 18-wheeler of its day, typically carrying huge amounts of a homogeneous commodity – such as lumber, cement, iron ore, chalk, coal, sugar and molasses.

This Schooner

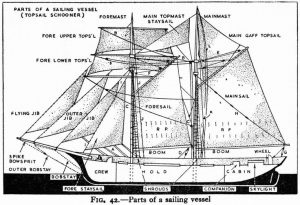

The Ada F. Whitney was a 312-ton, three-masted schooner. It was built in Thomaston, Maine in 1870, registered the following year in her homeport there and owned by the Wm. Whitney & Co. From the American Bureau of Shipping records, we learn she was constructed of oak, yellow pine with a single bottom and had iron fittings. Her assigned Signal Letters were “J. H. S. D.” This was an agreed upon system of identifying a ship’s name with corresponding books listing codes and names.

On the voyage of September 22, 1885, her captain was R. Gilchrist.

Final Voyage

On that fateful September day in 1885, the Ada F. Whitney was doing what so many other “work horse, 18-wheeler” schooners were doing along America’s Atlantic coast: hauling large loads of something from one port to another. On the morning of September 22, she was on her way from Boston, Massachusetts, to Brunswick, Georgia. At the time, she was “in ballast,” meaning she had delivered her cargo in Boston and had no cargo to pick up and was on her way to Georgia for a different loading of cargo.

In the forenoon of that day, Ida F. Whitney was passing off the North Carolina coast when the weather worsened. At about noon, during the prevalence of a fresh easterly gale, with rain, the three-masted schooner Ada F. Whitney was driven ashore on the North Carolina Outer Banks, about two and a half miles south of the Poyners Hill Station, near the present-day village of Duck, NC.

The crew of the United States Life-Saving Service Poyners Hill Station No. 9 “had watched her movements for some minutes before she struck. The schooner appeared to be unmanageable from the loss of canvas. When, therefore, it became manifest that she would soon be ashore, [the surfmen] set out with the beach apparatus, and in half an hour, were on the scene. This was with great difficulty encountered in getting there, the high tide of the morning having covered the beach and left it in a very soft and bad condition. By the time of their arrival she had driven in to within 120 yards of the shore and swung broadside to, with the seas breaking over her deck and the spray flying half-mast high. She was dangerously also rolling very deeply.” (Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 20, 1886, p. 117).

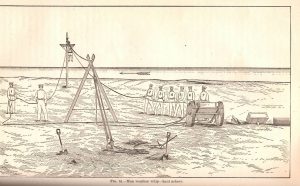

The Annual Report goes on to tell us that “The first shot from the Lyle gun lodged the shotline in the mizzen-topmast shrouds,” which was an ideal start. However, a basic understanding of how the beach apparatus process works is necessary to follow what happened next.

The Beach Apparatus

First, the full explanation: The beach apparatus was the collective term for the Beach Cart loaded with all its individual pieces. The Lyle gun was the most striking. It was a small, bronze 200-pound black-powder mortar designed specifically for this purpose. It has this unique distinction: it is the only gun in the history of humankind on this earth specifically designed to save, and not take, lives. Its muzzle would be loaded with a 20-pound steel projectile called the Shot which had the thin shot line tied to it. The objective is to have the shot pass OVER the ship’s rigging so that the shot line falls down onto the vessel somewhere. Then, someone aboard the stricken vessel, retrieves the line and begins to pull it in. While he is doing that, a surfman on the beach is tying the whip line to the shore end of the shot line (not shown; already employed). This is a block, or pulley, with a very long line running through it, appearing to be two lines. The block is tied high up to the mast and the surfmen spread out holding the two lines from the block in a ‘v’ shape on the beach. Now, if they tie something to one side of the whip line, and pull on the other side, that thing goes out to the ship. Reverse procedure to bring things back from the ship to the shore. Then, a thick line called the hawser acts like a zip line. Attach the breeches buoy to that and rescues can begin, bringing one survivor at a time safely to shore. This process was so effective that its last use by the Coast Guard was in 1962. A great visual for this is a film by Allan R. Smith found at www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhthLPIEnCO.

How did ships’ crews know what to do with this somewhat complicated procedure? First, a talley board was sent out with the hawser with brief written instructions. Insurance companies had a vested interest in reducing the loss of lives and cargo, so they printed a more comprehensive booklet entitled “Instructions to Mariners in Case of Shipwreck,” with words and illustrations. These were required to be onboard of any insured vessel, and they did help save lives.

Now, the Simple Version

This helps us to understand what the Poyners Hill crew faced: The lifesaving device rescuing the shipwreck survivors is the breeches buoy. It rides on the “zip line” of the hawser. This hawser MUST be kept extremely taught, in order to keep the buoy and survivor above the lethal waves they are escaping. In the drill, that is easy to do; the wreck pole does not move. However, a shipwreck in violent surf does move; and it moves a lot. In this case, the wreck is moving towards the lifesavers. Each foot of that movement slackens the tension on the hawser. Consequently, that requires constant adjustments of the beach apparatus components. The fall line must constantly be re-tightened. In some cases, it even required digging up the sand anchor and relocating it.

Working in this storm, with the added seemingly never-ending job of the more constant relocations of the beach cart, lines, sand anchors, and crotch pole, all seven of the schooner’s crew were landed safely on shore. That is what the U.S. Life-Saving Service does, but that is not all.

The survivors are taken back to the station and given dry clothes, food and drink, succor and first aid, if needed. Also, if needed, a place to stay until they can be picked up.

From the Annual Report: “While the rescue was in progress the district superintendent, Mr. T.J. Poyner, and Messrs. John C. Gallop and Josephus Baum, residents of the vicinity, joined the party and lent valuable aid. The keeper of the Caffeys Inlet Station, to the south, also came up and rendered good service. The latter had been watching the vessel from his station and started with the apparatus as soon as she struck but finding travel so bad with the heavily loaded cart he had pushed forward alone on horseback leaving his men to follow, and arrived in time to get the people ashore. The captain and mate were taken in charge by Superintendent Poyner and conducted to his home, while the rest were given quarters at the station, where they remained five days.” 4

The Good and Bad of the Ending

The Annual Report concluded: “During the succeeding night the schooner worked closer in and was flooded. On the following day, when the station crew boarded her to recover the crew’s effects, she was full of water and in such condition as to preclude the possibility of saving her. The station crew a few days later assisted in saving the water casks and part of the rigging, the anchors and chains and other heavy articles being recovered by the Baker Salvage Company, of Norfolk. The wreck was condemned and sold at auction.”

Good News: Crew all saved. Bad News: Ship nearly a total loss. As usual, the crews of America’s Forgotten Heroes succeed by saving lives – and then doing far more.

Busy Outer Banks Lifesavers

Amazingly, on the same day, the very next entry into the Annual Report of the Operations of the United States Life-Saving Service for the fiscal year ending June 20, 1886:

September 22. – At about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, during the prevalence of a northwest gale, with heavy rain, the lookout of the Big Kinnakeet Station, (Sixth District,) [now village of Avon, Hatteras Island] coast of North Carolina, observed a small schooner in Pamlico Sound, about four miles from the station, scudding under bare poles* directly for the beach. The surfboat was immediately got out and hauled a mile through the woods to the landing-place on the west shore. This task was not an easy one, as the thick growth of trees impeded the men in their movements and made the work slow and toilsome. About the time that the life-saving crew launched their boat the vessel, which could now be plainly seen with part of her sails blown away, let go both anchors, which brought her up a short distance from the shore. Her crew of two men landed safely on the beach and were taken by the surfmen to their homes. The schooner proved to be the Oran, of and for Hatteras, North Carolina, from Tar River, in the same state, with a cargo of wood. She rode out the gale without further harm and subsequently resumed her voyage.

These are excerpts from Chapter 13 in the sequel to James D. “Keeper James” Charlet’s Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, Globe Pequot Press (imprint of Rowman & Littlefield), 2020, with new, added material. Keeper James also presents “live theater” programs excepts from the book. Volume I has gone into second printing. The unpublished Volume II coming soon.