Near-perfect weather Monday for eclipse in OBX; NASA launching rockets that may be visible

Northeastern North Carolina and the Outer Banks will have near-perfect conditions to see the entirety of the partial eclipse on Monday, with mostly sunny skies and temperatures in the upper 50s to low 60s.

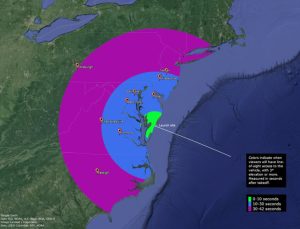

And three sounding rockets will be launched from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility on the Virginia Eastern Shore that may be visible from the region shortly after they liftoff.

The eclipse begins along the Outer Banks when the edge of the Moon touches the edge of the Sun, called first contact, at 2:04:45 p.m.

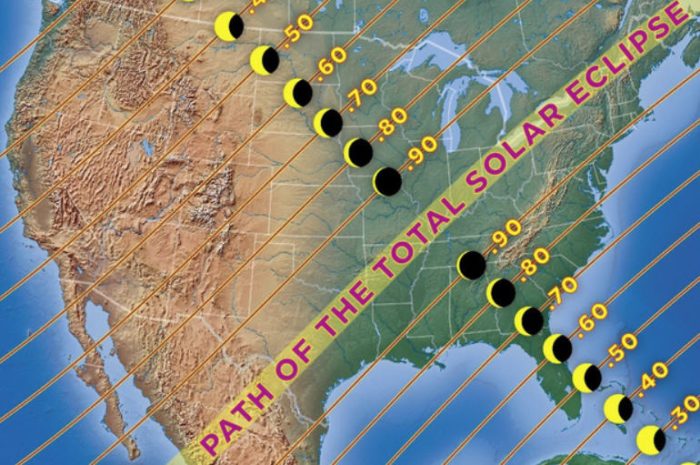

At its peak, about 71% of the sun will be blocked by the moon at 3:20:35 p.m.

The eclipse will end when the edge of the Moon leaves the edge of the Sun at 4:32:16 p.m.

The amount of coverage of the eclipse that will be visible will increase the farther inland you travel.

Regular sunglasses will not work to look directly at the sun, and only (ISO) 12312-2 certified lenses are considered safe.

And just in case you’re curious, the next time a total solar eclipse will be visible along the Outer Banks and in eastern North Carolina will be May 11, 2078.

The Atmospheric Perturbations around Eclipse Path (APEP) sounding rockets launching from Wallops Island will carry payloads to study the disturbances in the ionosphere created when the Moon eclipses the Sun.

The rockets had been previously launched and successfully recovered from White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico, during the October 2023 annular solar eclipse.

They have been refurbished with new instrumentation and will be relaunched on Monday.

The mission is led by Aroh Barjatya, a professor of engineering physics at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Florida, where he directs the Space and Atmospheric Instrumentation Lab.

The sounding rockets will launch at three different times: 45 minutes before, during, and 45 minutes after the peak local eclipse. These intervals are important to collect data on how the Sun’s sudden disappearance affects the ionosphere, creating disturbances that have the potential to interfere with our communications.

The ionosphere forms the boundary between Earth’s lower atmosphere – where we live and breathe – and the vacuum of space. It is made up of a sea of particles that become ionized, or electrically charged, from the Sun’s energy, or solar radiation. When night falls, the ionosphere thins out as previously ionized particles relax and recombine back into neutral particles. However, Earth’s terrestrial weather and space weather can impact these particles, making it a dynamic region and difficult to know what the ionosphere will be like at a given time.

It’s often difficult to study short-term changes in the ionosphere during an eclipse with satellites because they may not be at the right place or time to cross the eclipse path. Since the exact date and times of the total solar eclipse are known, NASA can launch targeted sounding rockets to study the effects of the eclipse at the right time and at all altitudes of the ionosphere.

As the eclipse shadow races through the atmosphere, it creates a rapid, localized sunset that triggers large-scale atmospheric waves and small-scale disturbances, or perturbations. These perturbations affect different radio communication frequencies. Gathering the data on these perturbations will help scientists validate and improve current models that help predict potential disturbances to our communications, especially high-frequency communication.

MIT Haystack Observatory/Shun-rong Zhang. Zhang, S.-R., Erickson, P. J., Goncharenko, L. P., Coster, A. J., Rideout, W. & Vierinen, J. (2017). Ionospheric Bow Waves and Perturbations Induced by the 21 August 2017 Solar Eclipse. Geophysical Research Letters, 44(24), 12,067-12,073. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL076054.

In addition to the rockets, several teams across the U.S. will also be taking measurements of the ionosphere by various means. A team of students from Embry-Riddle will deploy a series of high-altitude balloons. Co-investigators from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Haystack Observatory in Massachusetts, and the Air Force Research Laboratory in New Mexico, will operate a variety of ground-based radars taking measurements. Using this data, a team of scientists from Embry-Riddle and Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory are refining existing models. Together, these various investigations will help provide the puzzle pieces needed to see the bigger picture of ionospheric dynamics.

When the APEP sounding rockets launched during the 2023 annular solar eclipse, scientists saw a sharp reduction in the density of charged particles as the annular eclipse shadow passed over the atmosphere. “We saw the perturbations capable of affecting radio communications in the second and third rockets, but not during the first rocket that was before peak local eclipse” said Barjatya. “We are super excited to relaunch them during the total eclipse, to see if the perturbations start at the same altitude and if their magnitude and scale remain the same.”

The next total solar eclipse over the contiguous U.S. is not until 2044, so these experiments are a rare opportunity for scientists to collect crucial data.

The APEP launches will be live streamed via NASA’s Wallops’ official YouTube page and featured in NASA’s official broadcast of the total solar eclipse. The public can also watch the launches in person from 1-4 p.m. at the NASA Wallops Flight Facility Visitor Center.