Dozens of Coast Guard Personnel Come Together to Uncover the Heroes of the Past

U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) personnel from Elizabeth City to Hatteras Inlet came together in the tri-villages on Thursday to clean and uncover the gravesites of generations of lifesaving heroes.

The crew of roughly 65 personnel represented all ranks and a total of seven units, and their goal was to clear out and honor a collection of sites in Rodanthe where former Coast Guard and Life-Saving Service Station members – the predecessor of the USCG – were laid to rest.

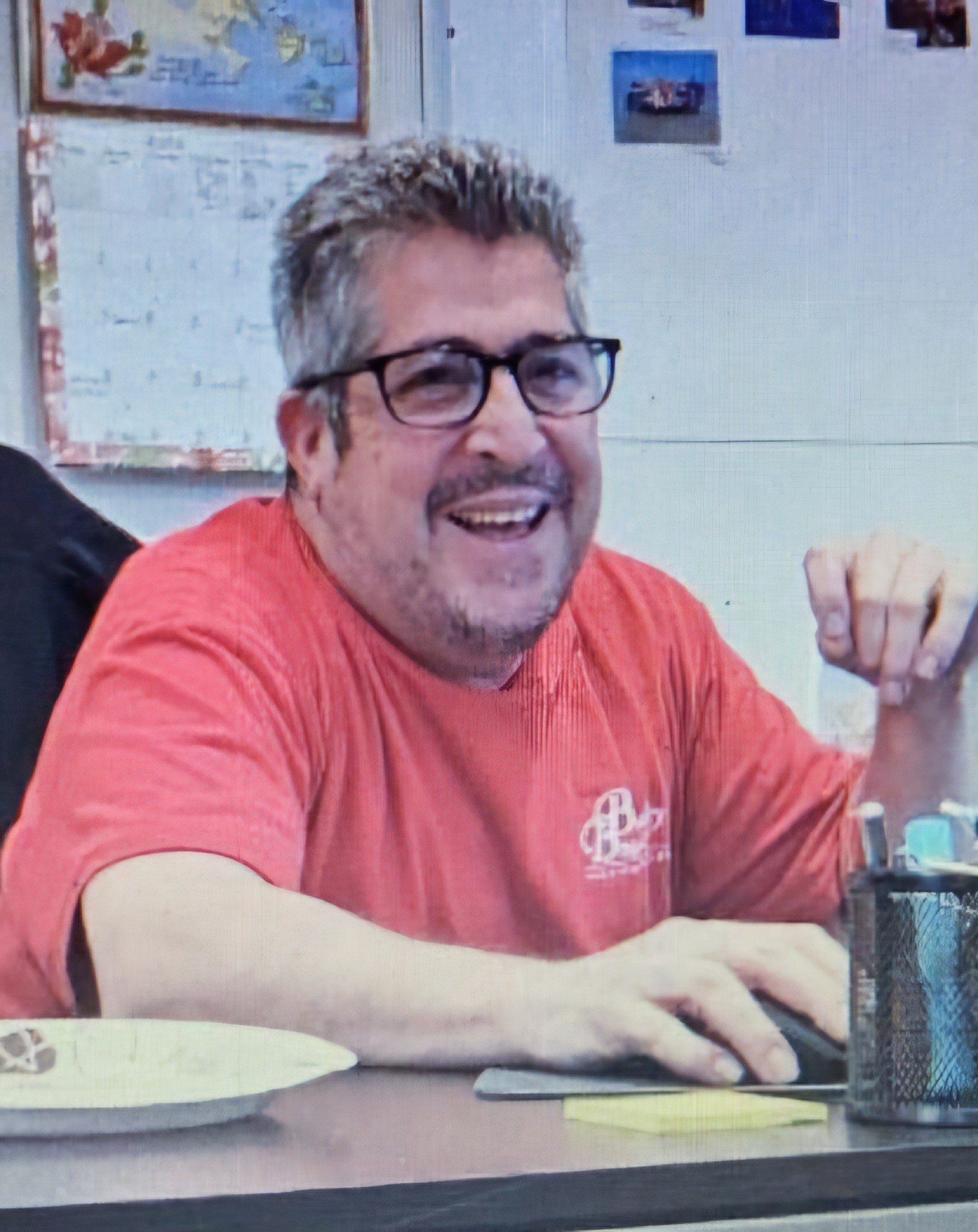

The idea initiated about a month ago, when Engineering Petty Officer Chief Jamison Smith and Chief Warrant Officer Ryan Gentry, (who has familial ties to the area), got together to discuss a number of gravesites that needed to be cleaned up. Tucked away behind rental homes and businesses, the graves of these past heroes were veritably hidden in plain sight, but had been covered by years of tree and brush growth.

“Ryan Gentry and myself wanted to do this as a community service project,” said Chief Smith. “When we looked at the sites, and saw the scope and the magnitude of the project, we knew we would need more help.”

Originally the project was going to be tackled by a small team of seven local USCG chiefs, but after touring the sites in question, it became clear that it was not a small undertaking.

“The 100th anniversary of the Mirlo rescue is coming up, and there are a lot of heroes buried here,” said Chief Smith. “These gravesites were just forgotten about over the years. The families maintained them as long as they could, but as people got older, the [maintenance] couldn’t be kept up… and we wanted to step up and honor them as best as we could.”

Noting that the project was “more work than originally expected” was a bit of a huge understatement.

It’s not exactly known the last time the four sites were cleared, but suffice it to say that huge trees and a wall of brush had grown in that timeframe, and a chunk of the graves that the volunteers uncovered were toppled over, or barely visible at all.

The small graveyard where the final resting place of Rasmus S. Midgett lies – a small patch of land that’s across the street from Lee O’Neal Road – was hidden under a line of brush that engulfed all but a sliver of the small wooden fence that protected the property.

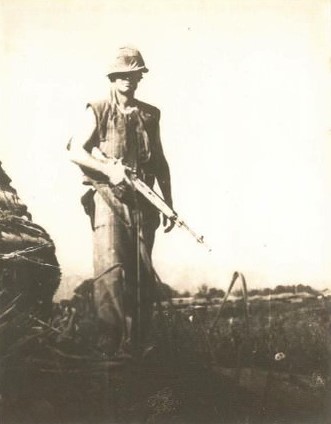

A local legend, Rasmus was a surfman with the U.S. Life-Saving Station, who on August 18, 1899, rescued crew members from the barkentine Priscilla. Working alone, Rasmus swam to the wreckage three miles south of the Gull Shoal Station to assist the survivors who were too exhausted to swim ashore.

“Rasmus S. Midgett single-handedly rescued ten men from the surf, and received the Gold Lifesaving Medal for his heroism” said Chief Smith. “But if you didn’t know that [his gravesite] was back here, you would never find it. You couldn’t even see the fence around the site.”

So after the idea was launched, word quietly spread about the forthcoming clean-up, and the need for assistance, and it didn’t take long for dozens of U.S. Coast Guard members to volunteer to help with the project.

Crew members from Station Hatteras Inlet, Station Oregon Inlet, ANT Wanchese, ESD Nags Head, SFO Nags Head, members of the First Flight Chiefs Mess, and multiple units of Elizabeth City all stepped up to the plate.

All ranks were represented, and the assembled volunteer team included divers, swimmers, aviation mechanics, machinery technicians, electricians mates, store keepers, aviation electronics technicians, and even one of just five Rescue Swimmer Master Chiefs in the entire U.S. Coast Guard, John Hall.

“It started out small, but it certainly became big, and quickly,” said Chief Smith. “We didn’t advertise it that much, at all – but all the people we did reach out to said they would be happy to help.”

The roughly 65 USCG members volunteered their time, their gas, and their own equipment for the project, and each of the four sites were a blaze of activity for several hours as trees were cut, brush was hauled out of the site by trailers, and graves were recovered and reset as needed.

The four sites were scattered throughout the northern Tri-villages and included a graveyard behind the Island Convenience Store, the small graveyard of Rasmus S. Midgett near the sound, a graveyard that was appropriately a shell’s throw away from the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station, and a larger graveyard near the Chicamacomico Water Tower that extended from N.C. Highway 12 all the way to the Pamlico Sound.

“You’ll be able to see the water soon,” said Chief Smith, as dozens of chainsaws and lawnmowers buzzed in unison.

Sure enough, in just an hour’s time, the all-but-forgotten site that originally looked like every other naturally brushy patch of Rodanthe was soon clear enough that the former U.S. Coast Guard and Life-Saving Station members’ graves could be seen from the highway.

“I can’t even begin to list all the names of the [heroes] at these sites, but they all have ties to the Life-Saving Service Station, the U.S. Coast Guard, or all of the above,” said Chief Smith. “And every rank from E2 to E9 and Officer are here to help.”

There were some surprises found along the way, as well.

At the small graveyard close to the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station where Levene Westcott Midgett was buried, (an officer-in-charge and recipient of the Silver Lifesaving Medal), the volunteers eventually uncovered what appeared to be a cylindrical water tank standing on its end.

As it turned out, the mystery metal object was a WWII-era mine, as well as a marker for the gravesite of the Chicamacomico Station’s dog.

As the story goes, the still-active sea mine was pushed up from the beach by a local in his Jeep, and stayed at its newly relocated spot, fairly close to the gravesites of former personnel. The neighboring Chicamacomico Station’s dog was eventually buried at the base of the mine – while it was still active, no less – and years later, the mine was eventually addressed and deactivated.

“It’s a piece of history we didn’t know about, for sure,” said Chief Smith. “But how could we ever know these stories if we didn’t come out, and talk to people, and make an effort to get involved?”

Chief Smith reports this first massive clean-up is just the beginning, too.

“There are gravesites everywhere throughout Hatteras Island,” said Chief Smith, “and we’re just hitting the tip of the iceberg. We looked for ties with the Life-Saving Service and the U.S. Coast Guard, and that’s where we started, but there’s a lot more to do.”

This was the inaugural project of its kind for the local Coast Guard Stations, but it won’t be the last.

Chief Smith reports that community projects like this one have never been a requirement, but from now on, the Coast Guard will tackle similar endeavors roughly twice a year for the years to come.

“This is our initial effort,” said Chief Smith. “I’m sure there are 10 more sites just like these that we don’t know about… and we also want to redo the fence around Rasmus [Midgett’s] gravesite… there’s just so much we can and will do in terms of community service.”

In the meantime, the assembled crew of about 65 volunteers rivals any landscaping company in the world.

In just a day’s work, the always-moving team transformed the final resting place of dozens of lifesaving heroes and their families, creating new landscapes that can be admired and honored without maneuvering through sky-high mountains of brush.

Using tons of efficiency and a bit of muscle, the ongoing operation went down like a streamlined rescue – with coordinated activity, and results that the descendants and families of the lifesaving heroes could be proud of.

“So many of these sites were almost forgotten,” said Chief Smith. “But seeing what we’ve accomplished today, and the respect that we are giving these heroes… it gives you chills.”