This is how it began. My affair with words. The commercial piece, at least. I was stumbling around Hatteras Island in the fall of 1975, a little over a year after graduating college with a forestry degree.

There were a few of us, the people from off, who arrived here in the 1970s. Many of us had at least a four-year college degree and a couple folks had some graduate credentials. We weren’t the disenfranchised roamers looking to avoid adulthood. We were willing to work, and we worked hard. We just weren’t ready for the 30-year-then-retire lifestyle. The locals, curious and perhaps at first a little hesitant, welcomed us. They rented us their empty houses and often gave us jobs fishing or as handy persons.

Some of the early folks who arrived here when I did came to surf. But many of us simply loved the elemental, controlled-by-the-weather lifestyle.

Summers here in the ’70s had some palpable charm — a charm different from the beach-going vacation vibe we see now. Life mostly took place on the soundside. Cash was harder to come by then, but the lifestyle didn’t really demand much. What fish couldn’t be sold became dinner. Collards grew in every side yard. Yard grass mostly didn’t exist. I can still close my eyes and see the front expanses of the early houses I rented. Occasionally, a house would have a shrub, perhaps bought at the farm supply store on a trip to Elizabeth City, clinging to life under an overhang where the rain or condensate from dense humidity would sustain it. These houses were surrounded by sand, hot and dry and peppered with sand spurs or prickly pears.

Most days started before sunrise with the sound of boat motors churning “out the creeks.” Every creek and ditch had at least one wooden boat tied up. In the afternoon, neighbors visited from house to house sharing news of the day’s catch or family goings on or speculation on tomorrow’s weather. Summer Sundays meant church first, followed by everybody piling into the beds of family trucks that carried us and picnics to the beach. How different from today when many of the folks on the island are visitors who spend their days sunbathing by the pool of their rental house. Don’t get me wrong. The visitors today are the lifeblood of our lives here. It’s just so very different.

At 22 with the world before me, the concept of committing to a career path was dauntingly unattractive. I had tried my hand at lifeguarding, cleaning fish, painting houses and one very short stint working in a restaurant. But summer jobs don’t pay the bills year-round, and I needed more work than I was getting.

The 1970s marked a moment of prosperity in America. Interest in conservation and recreation grew in tandem with the number of Americans who had more leisure time and discretionary income. At that time, Cape Hatteras National Seashore had a visitor contact station, as it was called, located in the Double Keepers’ Quarters nestled beneath the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. It consisted of a non-descript counter holding a few books and some brochures. The Department of the Interior had deemed Cape Hatteras as an up-and-coming vacation destination, and officials wanted to improve their interaction with visitors by setting up additional visitor sites, offering local books and literature, and interpretive programs about the region’s wildlife and history.

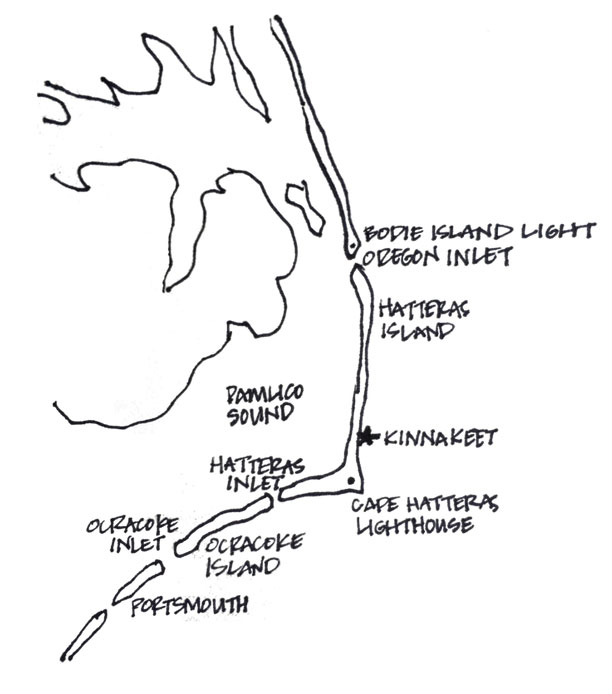

I was hired to set up the park’s new visitor stores that would be housed in historic structures along the Outer Banks from Bodie Island through Ocracoke. My bailiwick was Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands. Within some of the then-unrestored — and uncooled and minimally heated — structures, I set about putting together shelves from lumber found on the beach and mining publisher catalogs for appropriate titles.

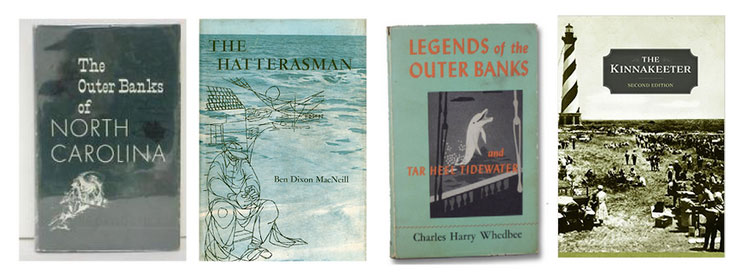

Back then, the books we offered included David Stick’s “Outer Banks of North Carolina,” Ben Dixon MacNeill’s “The Hatterasman” in the original hardcover, Judge Harry Whedbee’s “Legends of the Outer Banks” series and “The Kinnakeeter” by Charles Williams II.

Even today, these books are classics. But “The Kinnakeeter,” a book that sold and sold and finally sold out somewhere in the mid-1980s, became a particularly important part of my story on the island

In the slim volume of prose, Charles T. Williams II, tells the history of his village, “Kinnakeet,” one of the communities located on Hatteras Island which later became the village Avon. The Kinnakeeters were the earliest inhabitants of Hatteras Island, and both Native American and English blood flows through the veins of Kinnakeeters.

Mr. Charles chronicles the arrival early settlers who land on Hatteras Island when the ship John Evangelista ran aground in a storm. The shipwreck brought an O’Neal, a Meekins and a Williams, recognizable local last names to this day. He also details vignettes of daily life in Kinnakeet, reports of wrecks, war notes about who served where and in what battles, and provides a glimpse into the reorganization of the counties separating Hyde from Dare and the beginning of the influx of vacationers. Most of all, Mr. Charles makes it known that he is sure the mighty Creator placed his favorite souls in Kinnakeet as a great reward, so fond of the place is He. A charming, sit-on-the-porch-and-share-stories collection.

I read “The Kinnakeeter” for the first time kicked back in a creaky chair in the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Double Keeper’s Quarters where my office was located. Winters were long and quiet then. I read every book about the Outer Banks and especially Hatteras that I could find. I had met Mr. Charles when he delivered books to the new visitor contact station, so I was especially fascinated by his reflections on how his village came to be. Sitting in this historic, not-yet-renovated building, not 100 yards from the high-tide line, freezing even next to the fuel oil heater, I could transport myself back to the era of sailing ships and brave men. I realized even then that Hatteras Island was a place where Mother Nature ruled and I loved that.

By the time “The Kinnakeeter” sold out, I had finished my work on the visitor centers. My career at the lighthouse had begun to feel somewhat limiting. I looked at transferring to another park, but realized I had come to think of Hatteras Island as home. I had already bought a house and planted a garden. I faced the fact that, while not terrifically domestically inclined, I was surely a “nester.” I needed a home base that wasn’t a backpack. In the decade following my arrival on Hatteras Island, I had fallen head over heels in love with winter on Hatteras. When the wind moaned and shrieked, I was perfectly happy to hunker down and read until it quit blowing. I would imagine the long ago days when the lifesavers would be out walking the beaches in that kind of weather, looking for the masts of ships run aground. These brave men would then fling themselves into the surf, sheltered only by an open wooden boat, in an effort to rescue any possible survivors. This was the Hatteras I had come to know and leaving was no longer an option. I was home.

So in 1984, I opened Buxton Village Books. With a degree in Forestry that might seem an odd choice, but I had taken all my electives in English and was raised in a family of storytellers. During summer evenings in the mountains, we’d gather on our back porch and the adults would tell tales of Hiawatha or early ancestors’ exploits. Books were strewn around the house. Reading seemed a genetic inheritance. I knew words, but I knew nothing about business. But that’s the beauty of ignorance. I did not know what I did not know. I had a very steep learning curve ahead.

Somewhere around the year 2010, 25 some years after “The Kinnakeeter” went out of print, I was still slinging books at Buxton Village Books. More and more folks began asking about “The Kinnakeeter.” However, I was only selling new books, not old, collectible, or out-of-print books. That’s a whole different sort of business. Occasionally, I’d run across a copy of “The Kinnakeeter” at a yard sale or someone would give me copy when he or she cleaned out a relative’s belongings. These early copies were selling for well over $100.

As more and more people asked how to buy a copy of “The Kinnakeeter,” I began to think about initiating a reissue of it. Over the years, many of Mr. Charles’ descendants had opined how nice it would be to bring the book back into print. As these modern-day Kinnakeeters wandered in and out of my store on their usual book-buying visits, I would mention my interest in helping bring “The Kinnakeeter” back.

On one rather regular day, Annette Williams O’Neal, Mr. Charles’ granddaughter, the assistant principal at our local high school, came into the bookstore and said she had decided she was serious about spearheading the family effort to bring back “The Kinnakeeter.” She asked if I would I help and, I was thrilled to say, “Of course.”

“The Hatterasman,” also out of print for many years, had recently been brought back into print by the publishing lab at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington. Folks loved it, and it was selling steadily. Originally published by the venerable North Carolina publishing house John F. Blair, the copyright to “The Hatterasman,” a key to any book’s reissue, had a track record.

“The Kinnakeeter” was a different story. Self-published by Mr. Charles though Vantage Press — a company then known as a “vanity press” because the author paid the company to print his book — Mr. Charles owned the original copyright, and after a lapse of nearly 30 years, it was unclear who rightfully held the copyright. No one seemed to have any idea if Mr. Charles had left a will, or if he did leave a will, where it might be and, further, if the will mentioned the book. No one had a clue. Finding the copyright was an important obstacle in re-issuing the book. And without taking up several paragraphs with copyright minutia suffice it to say, I consulted the Library of Congress and, as so often happens in life, the will was discovered after all the work was done that needs done if there is no will. So the title page of the reissue bears a fresh new copyright.

The first publisher I reached out to was Edwina Woodbury at Chapel Hill Press. I had recently worked with her to publish two books by a local author on the history of the Rodanthe, Waves and Salvo area. The books were lovely, well-priced and had been selling like hotcakes.

Edwina, a veteran publisher, began to shepherd me, in her sophisticated, classy and cultured way, through the copyright morass and reissue process.

Along the way, I sacrificed one of my own original hardcover copies of “The Kinnakeeter” to the scanner so we could reproduce the original text and photographs exactly. I thought that was important. I wanted a book that looked contemporary but was true to the original.

The cover photo was another matter. The original cover showed a gathering at Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. It was noted on the copyright page as the 1955 Pirates Jamboree. I knew there were many pictures of the Pirates Jamboree, which was historically an all-day event on the grounds of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, featuring a fish fry, horse racing, and a contest for the best pirate beard, at the Outer Banks History Center. After many hours of searching, the very industrious history center archivist, Stuart Parks II, determined that that particular photo was not to be found.

Within a few days, John Havel, researcher and lighthouse aficionado extraordinaire, crossed the threshold of Buxton Village Books.

“John!” I said “I bet you would know…” And I quickly — well, in conversation with John nothing is quick, but within an hour, let’s say — laid out The Kinnakeeter cover dilemma. I nearly fell over when he said, “I have that picture in a high-def resolution. I was looking for something else and found it misfiled at The History Center”

Do I believe in magic? You bet I do.

So when John left the island later that day to return home on the mainland, he called back and said, “Send me a scan of the hardback “Kinnakeeter” cover so I can compare details to be sure.”

That’s the kind of accuracy I appreciate.

And it was indeed the correct image. Soon it was winding its way through cyberspace to the publishing house. After a 10 year journey the final puzzle piece had fallen into place.

In March of 2016, “The Kinnakeeter” was reborn.

While the reissue is a terrific success story of saving island history, no one will retire from the profits. It required a significant investment of time and money to bring back. Partnering with John Blair for distribution will ensure legitimacy and long-term success. To be included in a well-respected publishers catalog is a big win. We are all happy with that.

And for me it’s an even bigger win. I got to sell the original hardcover the very year it came into being, and here, these many years later, I got to be part of bringing this island classic back to life.

Hatteras Island today is hardly recognizable when I reflect on my early years here. I can wander down some side roads in the villages and find empty lots where once stood lovely wood frame homes. The creeks no longer shelter wood boats. A few skiffs tied up here and there look almost like movie sets so picturesque, surrounded by pastel rental homes. But I stay. I stay because there is a chance I can make a difference here. I can give back to the place that has given so much to me.

I hope to continue selling books, including the handsome new edition of “The Kinnakeeter,” for many years to come. When I’m dust, I don’t much care what goes on in the world. By then it will no longer be any of my business. But I will be happy to leave even a tiny legacy in helping to preserve a story of this very special place.

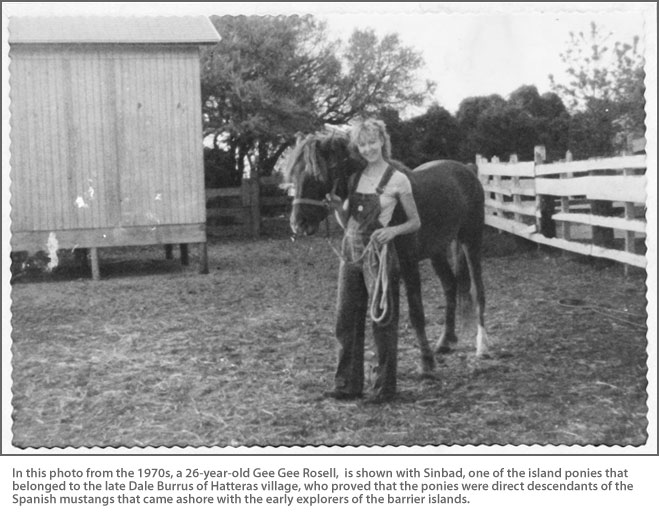

(Gee Gee Rosell is the owner of Buxton Village Books. Baxter Miller is a co-founder of Bit & Grain, a website dedicated to telling the story of North Carolina and its people, places, and culture. This column first appeared in Bit & Grain and is reprinted with permission. To read more Bit & Grain, go to http://www.bitandgrain.com/.)