Coyotes emerge as coastal predators — even on the seashore

Wily, intelligent and adaptive coyotes are in all 100 counties of North Carolina and they are here to stay.

“They are set up to use the habitat,” said Chris Kent, a biologist with the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission whose district includes the state’s largest coastal cities.

Chris Turner, a commission biologist in the northeastern part of the state agrees that coyotes are highly adaptable and can live in rural, suburban and even urban areas. “Being omnivorous, they can utilize many food resources, ranging from small mammals to fruit/berries to agricultural crops to dog food and table scraps,” he explained in an e-mail.

Originally native to the grasslands and prairies west of the Mississippi River, coyotes first became permanent residents of the state’s mountains in the early 1980s. Within 30 years, they reached the Atlantic Ocean.

Although the evidence points to large populations in coastal North Carolina, they are rarely seen. “They are very wary of people and you just don’t see them very often,” Kent says.

And it may not be apparent to an untrained eye just what has been seen. At first glance, a coyote may look like a medium-sized dog or a small German shepherd, but with a more pointed muzzle and flatter forehead. They also tend to be thinner than domestic dogs, although in the winter they will look bigger because they are carrying a heavier fur coat.

Canis latrans is a remarkable species of canid. From its original habitat west, it has spread throughout North America and is found in every country of the continent.

The migration of the coyote began soon after European settlers took control of North America. Intent on creating a safe landscape to farm their fields and raise livestock, settlers hunted apex predators — wolves, cougars, bears — almost to extinction.

“It’s generally understood that there was a canid top predator,” explained Pete Benjamin, field supervisor for the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s Raleigh office. “On the East Coast, cougars and the red wolf were eliminated, and coyotes have filled that niche.”

The service’s red wolf recovery program in Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in Dare and Hyde counties has brought the eastern red wolf and coyote into direct contact. In the western United States where the larger grey wolf lives with coyotes, the coyote becomes prey.

From its original habitat in the West, the coyote has spread throughout North America. Map: Cook County, Ill., Coyote Project and Ohio State University

The smaller red wolf, although larger than a coyote, seems more likely to avoid interaction for the most part. “Until mating season,” said Woody Webster, site manager for the state’s Buckridge Coastal Reserve in Columbia. The Buckridge Reserve borders the federal refuge.

Typical of the genus canis, coyotes can cross breed with dogs and wolves. “When opportunity may present itself, canids, including coyotes, are physically capable of cross-breeding, “ Turner said.

Fish and Wildlife biologists, worried about crossbreeding between coyotes and red wolves, came up with what they hope is an innovative approach. “The issue of hybridization is a concern, and we’re managing the interaction between the species,” Benjamin explained.

Like all canids, coyotes are territorial, and studies have shown that sterilized coyotes retain their territorial instinct. “We have place holders using sterilized coyotes. Sterilized coyotes will defend against other coyotes,” Benjamin said. “They’ll keep the territory from other coyotes until the wolves take over or we insert wolves (into the environment).”

No one is sure how many coyotes live along the coast. Scott Crocker has managed the state’s reserve sites along the northern coast for the past three years. “I have seen evidence pretty much since I’ve been here,” he said. “Each year there’s maybe a half dozen that I actually see. I’ve definitely seen the evidence. Scat with fur in there and we have game trail cameras at both sites.”

No one has seen a coyote at the Coastal Reserve sites along the southern coast, including at Masonboro Island, Zeke’s Island, Bald Head Woods and Bird Island, but there is evidence that they have been visiting if not living in some of the more accessible parts of the reserve, according to site employees.

Landowners often consider coyotes nuisances that can cause damage. “Unprotected poultry and livestock can . . . be harmed in some situations,” Turner wrote in his email. “Coyotes can also take small dogs that are left to range free or are left unattended.”

The eastern red wolf, shown here, is slightly larger than the coyote. Photo: Wolf Haven International

Because of the potential for damage to farm production and the designation as an invasive species, the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission allows the hunting of coyotes at any time throughout the state. The exception is the five counties where red wolves live — Beaufort, Dare, Hyde, Tyrrell and Washington. In those counties a special permit is required.

It is doubtful, however, that open season on coyotes is an effective means of controlling the population. Wildlife biologists point to the reproduction characteristic of coyotes that makes controlling the population so difficult. Typically a coyote litter will be five to seven pups. If a coyote population in an area becomes too dense, the litter size drops. If the population is thinned either through disease or hunting, litter size increases — and may increase substantially — doubling in size over the average. Additionally, female coyotes will go into heat at a younger age.

This is a well-documented phenomena and one that the Wildlife Commission seems to address in its 2012 report on fox and coyote populations. “In all cases, the use of bounties has been an ineffective and inefficient tool for controlling coyote populations,” the study authors wrote.

Although there have been no systematic population studies of statewide or regional coyote population, that report offers indications of how widespread coyote populations are in North Carolina. A little more than 4,000 animals were killed by hunters in 2007-08, the report notes. Two years later, that number had more than doubled to more than 10,000.

Other animals have had to adapt to what is apparently a very healthy coyote population in eastern North Carolina, Turner wrote. For instance, the populations of those that compete with coyotes, like red foxes, have declined.

“Some small mammal species may now have another predator to deal with, resulting in increased mortality during the year,” Turner continued. “Increased mortality of some species, especially those small mammals that may destroy the nests of some ground-nesting birds can actually be beneficial for other native species.”

POSTSCRIPT: Coyotes on Cape Hatteras National Seashore

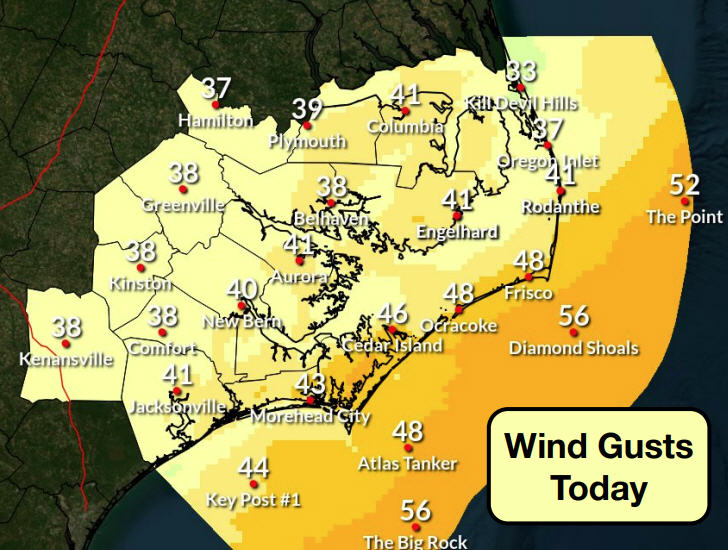

Coyotes are not common on the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, according to Randy Swilling, the Park Service’s natural resources program manager, but they are here — especially on Bodie Island.

They are also on Hatteras Island, but Swilling says as far as the National Park Service knows, the predators haven’t made it to Ocracoke yet.

“They’ll eventually be on Ocracoke,” he said. “They may already be there, just in such small numbers that we haven’t run across them yet.”

Swilling says the coyotes have especially been a problem with pedation of tern colonies on Bodie Island.

On Hatteras Island, he says, they have been trapped as part of the predator control program for several years. Rangers often see their tracks, he said, adding that they seen the tracks all the way out to Cape Point. And earlier this month, a coyote was run over on Highway 12 near Sandy Bay just outside Hatteras village.

Coyotes can swim, Swilling said, though park officials think that the animals got to Hatteras the same way the rest of us have — on the Bonner Bridge.

Obviously, they will have to swim — or hitch a ride on a ferry — to get to Ocracoke.

And, that’s possible, Swilling said, because there are coyotes on Cape Lookout National Seashore, which is south of Ocracoke and accessible only by boat.

(Postscript contributed by Island Free Press Editor Irene Nolan.)