Island History: The Wreck & Rescue of Ephraim Williams on December 22, 1884.

It was the Maker of Mottos and Heroes 138 Years Ago, and Became a Christmas Miracle

“On 22 December 1884 the crew of the Cape Hatteras (NC) Station (Sixth District), performed one of the most heroic feats in the annals of the Life-Saving Service. Under the leadership of Keeper Benjamin B. Dailey, assisted by Keeper Patrick H. Etheridge, they rescued the nine men composing the crew of the barkentine Ephraim Williams.”

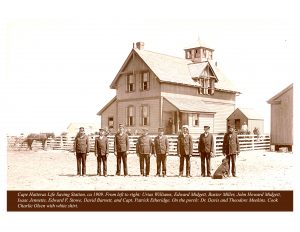

So begins the official United States Coast Guard account of the awarding of the Gold Life Saving Medals to Creed’s Hill LSS, NC (Station No. 22, Sixth District) and Cape Hatteras LSS, NC (Station 23, Sixth District) – Awardee(s): Keeper Patrick H. Etheridge, Keeper Benjamin B. Dailey, Surfman Isaac L. Jennett, Surfman Thomas Gray, Surfman John H. Midgett, Surfman Jabez B. Jennett, Surfman Charles Fulcher (From USCG website: https://www.history.uscg.mil/Browse-by-Topic/Notable-People/Award-Recipients/Gold-Lifesaving-Medal/).

This episode was the creator of the ‘Mother of Maritime Mottos.’ Following the duration of this lengthy and painful story will likely also exhaust the reader. However, it has a happy ending: it gives rise to one of the most famous quotes still used daily by the United States Coast Guard – “That Others May Live.”

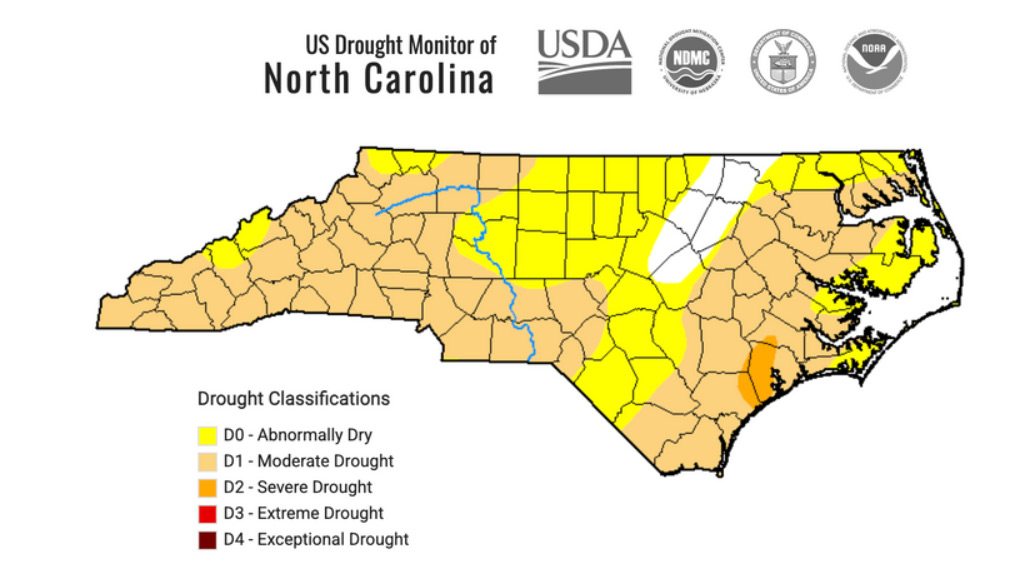

The Dreaded Cape Hatteras

Even casual readers of North Carolina maritime matters know the dreadful reputation of Cape Hatteras for shipwrecks. Why so much here? Because here is the confluence of a number of factors that, put together, make an almost unique situation:

- The discordant directions of the Labrador Current and the Gulf Stream

- the power generated when those two currents clash at Cape Point

- the 20 miles of deadly and shallow Diamond Shoals

- the conflicting directions of prevailing seasonal winds

- the captain’s choice of saving time by going close to shore versus the safety of sailing the longer route out and around

- the 300 miles of barrier islands affording no safe port; and the big one: storms!

This is where our story ends, but it began far away.

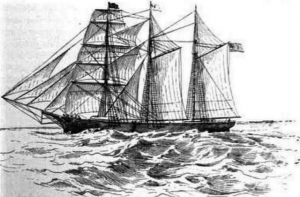

The Ship

From the Merchant Vessels of the United States, (for the full name, see graphic) Years Ending June 30, 1886, we learn the following about the barkentine Ephraim Williams:

She was 125 feet long, 27 feet wide, and had a depth of 11 feet. She had a gross tonnage of 491 and the net was 466. Her official sailing number was 8030. The most important number in all those details for us to appreciate in this episode was this – the year she was built, which was 1857. That means when she sailed in 1884, she was a 27-year ‘old lady.’

The ‘Odd’ in Odyssey

Almost every factor in this odyssey was a negative one. The first mistake: The barkentine itself was an old vessel that should have been retired long ago. Ships at this time were built from local wood and sealed with tar, which was the only available waterproofing. While it is true that some wood is much better than others for this purpose, no wood is waterproof. The basic equation has always been: wood + water = rot. Wooden sailing ships thus had a life of approximately 20 years. Ephraim Williams was dangerously beyond that.

The second mistake: The vessel was a 491-ton barkentine carrying a cargo of lumber leaving Savannah, Georgia and bound for her homeport of Providence, Rhode Island in the winter of 1884. This meant leaving Savannah and proceeding north, she would have to navigate and negotiate all three Capes: Fear, then Lookout, then Hatteras.

Unfortunately, she had scheduled this trip during a time the U.S. Life-Saving Service called “the storm season.” The Williams first encounter was with the Frying Pan Shoals off Cape Fear. These shoals form a very large hazard to navigation created by silt and sand deposits from the Cape Fear River near Wilmington, N.C. The shoals extend 28 miles out to sea.

The third mistake: She stayed out of port when she encountered a ferocious storm off the dreaded Frying Pan Shoals. The pounding of the storm had waterlogged her. She became totally unmanageable and therefore at the mercy of the winds and currents. Those same winds and currents carried her up the coast from Wilmington towards the worst place for her to be in such poor condition: Cape Hatteras.

The Odyssey Itself

Then the agonizing “intermission” between the beginning and the end of a foregone conclusion. She drifted for 180 miles. Lucky for the vulnerable Ephraim Williams, the United States Life-Saving Service by then had established 22 Life-Saving Stations along the North Carolina coast, ranging from the southern-most 1883 Cape Fear Station to the northern-most 1878 Deals Island Station (later renamed Wash Woods).

Due to the rigorous standards and training of these stations, the NC beaches were covered 24 hours a day, seven days a week, which was a monumental task.

If a shipwreck occurred, a station would know about it within minutes, even in these extremely isolated locations. It might take them hours to get there, but they knew of it and took action immediately.

How did they do this? Every station had a watch tower, usually a separate tower on the highest level above the roof. This obviously did not work at night nor on days with visibility obscured by fog, rain, or storms. Then it was time for the beach patrol. Two surfmen from each station were sent to the beach all at the same time. They would walk in opposite directions, heading towards their neighboring station.

Because of this strict duty, the wounded barkentine was spotted three days after the storm had crippled her, December 21, by the lifesavers on beach patrol from the United States Life-Saving Service Stations of Durant’s (Hatteras Village), Creed’s Hill (Frisco) and Cape Hatteras (Buxton).

Even worse, the Ephraim Williams, and the Gulf Stream, had brought the storm with them. The seas were now described in the official report as “mountainous high.” The captain decided to “let the anchors go” (drop them) in hopes of stopping the drift towards the even more dreaded Diamond Shoals where the ship would surely break apart.

The Life-Savers’ Marathon of ‘Musical Chairs’

The seas were too rough for the surfboat rescue, and the Ephraim Williams was much too far out – estimated to be six to seven miles offshore – for the breeches buoy rescue, and all the lifesavers could do was watch in frustration.

The surfmen of Stations Durants, Creeds Hill, and Cape Hatteras were like petrified statues valiantly standing by. One of the most remarkable facts about the thousands of surfmen from nearly 300 stations nationwide of the U.S. Life-Saving Service throughout the entirety of their 44 years of service was their incredible persistence. They just never gave up. The morning watch found the ship had drifted considerably and had grounded hard and became stuck in Diamond Shoals, so far north as to be stranded opposite the Big Kinnakeet Station in Avon. The ship would soon be torn apart.

Decisions had to be made immediately, and they would surely be life or death decisions. Yet, there could only be one decision: the lifesavers would respond.

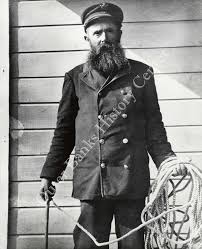

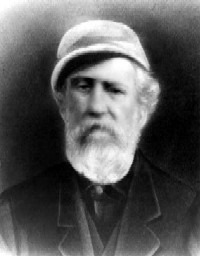

The Big Kinnakeet crew had spent the night at the Cape Hatteras Station, the last known location of the ship, so they quickly raced back to their own station. After a quick breakfast, Station Keeper Benjamin Dailey (very often misspelled as “Daily”) brought up the surfboat on its horse-drawn cart. At no time during this entire saga had there been any sign of life seen from the ship. After all these hours of harsh weather, storms, and jostling, it would be easy to assume there was a reason for no sign of life – that there was none left to save. Most of the local observers were of that opinion and said so. But not the lifesavers; their vigil continued.

The Miraculous Rescue

Some of the most graphic and powerful words come from a report in The Coastland Times, Manteo, N.C. of August 31, 1956, Page Two, here deserving of extended quotes.

“The Cape Hatteras men were soon ready. They lashed all loose articles in the boat, stripped off clothing that might in any way impede their movements in case of a capsize, and then, donning their cork belts, at the word from the keeper, shoved the boat in and gave way. A glance seaward revealed a towering and almost unbroken wall of tumultuous water, which seemed to threaten destruction to any craft defiant enough to give battle. But away beyond in the offing there were lives in peril which must be saved at any hazard. To those who had assembled on the shore it seemed a forlorn hope and a few dared believe it would be successful. The breakers on the inner bar, immense in themselves, were crossed in safety, but then came the infinitely more hazardous passage on the outer bar, nearly half a mile from the shore, where the billow met the first shock of resistance as they thundered shoreward. The whole scene was awfully grand, and enough to make the stoutest hearts quail.”

Another Motto is Born

Prior to the Cape Hatteras surfboat launch, one of the crew asked to be relieved since his wife was dying at home. Keeper Patrick Henry Etheridge of Creeds Hill Station volunteered to take his place.

Later, starting in 1891, Patrick Etheridge was also Keeper of the Cape Hatteras Life-Saving Station and became a legend. An eye-witness at the time tells the story:

“A ship was stranded off Cape Hatteras on the Diamond Shoals and one of the life-saving crew reported the fact that this ship had run ashore on the dangerous shoals. The old skipper (Etheridge) gave the command to man the lifeboat and one of the men shouted out that we might make it out to the wreck, but we would never make it back. The old skipper looked around and said, ‘The Blue Book says we’ve got to go out and it doesn’t say a damn thing about having to come back.'”

The Cape Hatteras surfmen launched their surfboat. They said their boat’s oars were powered by “Arm-Strong Engines.” To reach the Ephraim Williams they had to row through not four or five massive breakers, but they had to row through FIVE MILES of them! The entire 20 miles of Diamond Shoals is an underwater sandbar.

Again, the words of the 1956 Coastland Times writer:

As Dailey neared the billowy banner, he held his boat in check for a brief period awaiting his chance. The chance came before long, when the huge combers directly ahead flattened out in seething, roaring foam. Quick as a flash the word was given to the hardy rowers, and before the angry water could again rear herself, a few powerful strokes with the oars had carried the boat safely beyond the bar, and the greatest danger was past. It was a marvel to the people on shore how the sturdy fellows got through. It was so magnificently done. There were times when the entire interior of the boat could be seen as it mounted the seas, and the watchers held their breath, fully expecting to see it topple backward, bottom up.

When the lifesavers’ surfboat finally reached the sinking ship, they realized that if they were to pull up alongside, the violent waves would crush them and their boat. Instead, they anchored a close way off, threw a line to the ship, and then took the nine-man crew off one at a time. The Ephraim Williams’ crew had suffered December cold, hunger, and battering by the surf for 90 hours! Still, they had a long way to go before they slept, rowing five miles back through that awful surf – miraculously, all made it safely.

The Heartwarming Epilogue

That year, men of the United States Live-Saving Service stations, nationwide, had responded to and saved 2,439 lives in peril from the sea. The nine-man crew of the Ephraim Williams was part of that number of lives saved by this selfless Service.

The Life-Saving Service Supervisor detailed to inquire into the circumstance of the gallant affair closed his report with the following remarks. These were only meant for bureaucrats inside the Service, but they quickly resounded far and wide. Many Coast Guard facilities have adopted this motto.

“I do not believe that a greater act of heroism is recorded than that of Dailey and his crew on this momentous occasion. These poor, plain men, dwellers upon the lonely sands of Hatteras, took their lives in their hands and, at the most imminent risk, crossed the most tumultuous sea that any boat within the memory of living men had ever attempted on that bleak coast, and all for what? That others might live to see home and friends. The thought of reward or mercenary appeal never once entered their minds. Duty, their sense of obligation, and the credit of the Service impelled them to do their mighty best. The names of Benjamin B. Dailey and his comrades in this magnificent feat should never be forgotten. As long as the Life-Saving Service has the good fortune to number among its keepers and crews such men as these, no fear need ever be entertained for its good name or purposes.”

The quote “The names of Benjamin B. Dailey and his comrades in this magnificent feat should never be forgotten,” is repeated for emphasis. Those names, for this particular rescue, were Keeper Patrick H. Etheridge, Keeper Benjamin B. Daily, Surfman Isaac L. Jennett, Surfman Thomas Gray, Surfman John H. Midgett, Surfman Jabez B. Jennett, Surfman Charles Fulcher. Big Kinnakeet Station by Keeper Scarborough was also involved in the important succor afterwards.

These are important family names still proudly living on the Outer Banks, mostly on Hatteras Island, preserving this incredible history.

Three days before Christmas of 1884, the Life-Savers of Hatteras Island gave the crew of the Ephraim Williams the best present of their life.

This article contains much new material as well as excerpts from Chapter 11, Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks: Dramatic Rescues and Fantastic Wrecks in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, Globe Pequot Press (imprint of Rowman & Littlefield), by James D. Charlet, © 2020. James D. Charlet also performs a variety of “live-theater” programs for “Keeper James Presentations” based on extracts from chapters in his book. He can be reached at keeperJamesLSS@gmail.com.

Keeper James will also be hosting a presentation on the wreck of the Ephraim Williams on Tuesday, March 7 at the Hatteras Library. For more information, click here.