Judge Boyle hears oral arguments in CHAPA lawsuit to scrap the Park Service ORV plan

March 24 was the presumed date for oral arguments to be presented in the case of the Cape Hatteras Access Preservation Alliance (CHAPA) lawsuit challenging agencies of the Department of the Interior. The date and time and even the location of the hearing had remained uncertain until less than a week earlier, leaving attorneys for both sides and other interested parties with their calendars on hold.

At issue was a motion by CHAPA, as plaintiff, for summary judgment to scrap the National Park Service’s beach access management plan for the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Recreation Area. The federal defendants – the DOI, the Park Service and Barclay Trimble as superintendent of the Seashore — had filed a cross-motion for summary judgment to scrap CHAPA’s lawsuit. Also in the arena was the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), representing the Defenders of Wildlife AND the National Parks Conservation Association, admitted as Defendant-Intervenors.

The oral arguments were not requested by any of the parties to the lawsuit but by U.S. District Court Judge Terrence Boyle, who oversaw the lawsuit by SELC and its clients in 2007 against the Park Service for its lack of an ORV plan in 2007. That lawsuit was settled by a Consent Decree in 2008.

The courtroom in the Federal Courthouse in Elizabeth City was full of lawyers as Judge Boyle took the bench at 10:30 a.m. Attorneys Jonathon Simon and Todd Roessler represented the plaintiff, CHAPA. Department of Justice attorney Joseph Kim argued for the federal defendants. Derb Carter led a small SELC delegation, and his colleague Julie Youngman sat at the defendants’ table. Seashore superintendent Barclay Trimble and chief ranger Paul Stevens represented the Park Service. John Couch, Jim Keene and David Scarborough were among those observing on behalf of the Outer Banks Preservation Association, CHAPA, and the people of Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands.

Jonathon Simon opened the plaintiff’s argument in favor of summary judgment by reviewing the provisions of the 2008 Consent Decree and stating that the case before the court is about the failures of the Park Service management plan.

Less than a minute into Simon’s presentation, Judge Boyle interrupted: “Read the Enabling Act [the Congressional Act that in 1937 established the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Recreational Area and laid out its purposes of public recreation and wildlife conservation.] Do you see anything in the Act about ORVs?”

Missing the opportunity to note that neither plovers nor loggerheads are named in the Act, Simon admitted that he did not see anything about ORVs. But, he went on, ORVs are an important modern transportation technology, just as horses and feet were in 1937.

“Congress has amended the Enabling Act,” Boyle said, “but not to put modern technology on the beach.”

“The Park Service recognized that technology has changed,” Simon replied, “and put in vehicle access ramps and parking.”

Simon’s point seemed to be lost as the judge pushed on. “In the early 2000s, Cape Hatteras was the only seashore on the East Coast without an ORV plan. Your client sat on the negotiating committee to draft one. Your client was a party to the Consent Decree.”

Simon tried again. “The Enabling Act states that recreational uses ‘shall be developed.’”

“And the remainder to be permanently reserved as wilderness,” Boyle said. “What was the seashore like in 1937? How much was wilderness?”

Trying to get back to his argument, Simon said, “The Park Service’s FEIS [Final Environmental Impact Statement] is incorrect on several points.”

Judge Boyle was having none of it. “What does your client want? Do you want no plan?”

“No,” said Simon, “we want the National Park Service to obey the law.”

“How can the Park Service protect wildlife if it allows unlimited driving?” asked the judge with some exasperation.

“We’re not arguing for unlimited access. We hold that the Park Service acted capriciously in developing the management plan. It didn’t take into account Section 4 of the Enabling Act. They failed to explain the conclusions of the FEIS and in their cross-motion and called that a ‘harmless error.’ The FEIS refers to changes, but there’s no description of the baselines used in the FEIS. We have to ask changes relative to what?”

Simon proceeded to take apart the Park Service’s plan. “The lack of reasonable action alternatives undermines the public’s ability to comment. The plan sets out beach closures that aren’t supported by evidence, and the Park Service gave no recognition to CHAPA’s arguments against closures that serve no purpose.

“The plan’s parameters don’t recognize the dynamics of the seashore ecosystem. There’s no flexibility to accommodate changes in the beaches and the species. The Park Service says ‘If there are changes, we might review the plan.’ The Park Service’s processes have been fundamentally flawed, resulting in a flawed plan.”

Judge Boyle raised another topic, the standing of CHAPA to bring its lawsuit in the first place. That standing was challenged by the federal defendants, and Simon stated that CHAPA rejects the challenge.

Department of Justice attorney Joseph Kim rose to argue against CHAPA’s motion for summary judgment and in favor of the defendants’ cross-motion. “The Enabling Act is a red herring. Land use is not a central issue here.”

Judge Boyle broke in. “Let’s get some perspective. The seashore has been in violation of federal policy for 35 years. That abuse couldn’t continue. They were using an Interim

Plan because there was no plan. Having a plan or not having a plan is not a discretionary matter.”

“The Park Service did a needs analysis as part of plan development,” Kim observed.

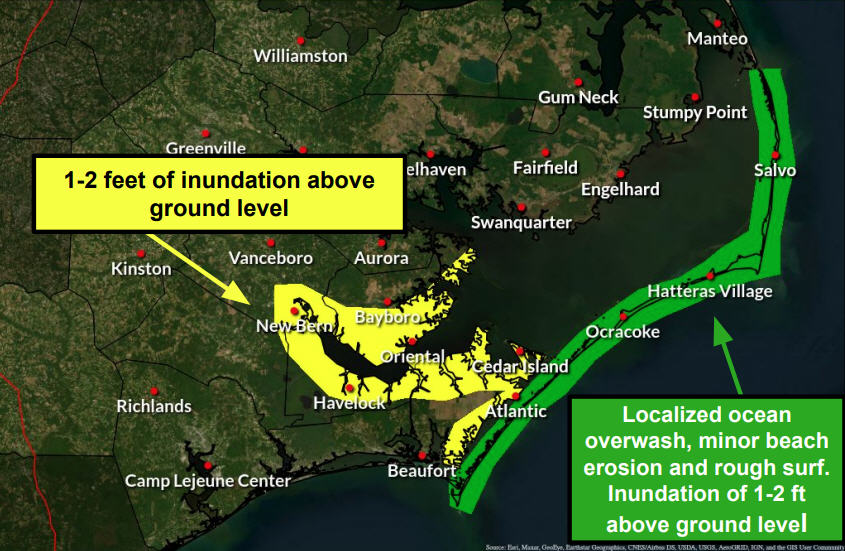

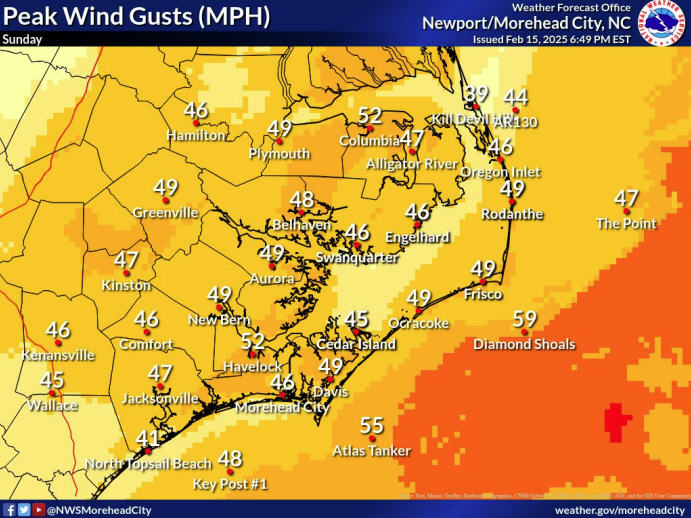

Undistracted, Judge Boyle went on. “Most of the seashore land is south of Oregon Inlet. When the bridge goes out, the islands are inaccessible. Weather, physical structures, storms limit access to the seashore. The Outer Banks are subject to drastic circumstances. So opportunities to operate ORVs on the seashore beaches are situational.”

The SELC attorneys, who continue to block the replacement of the Bonner Bridge, did not bat an eye at the judge’s reference to the potential consequences of their efforts.

“There’s no dispute,” Kim said, “that Alternative B is the best and the No-Action Alternative provides a baseline for comparison. The Consent Decree describes the status quo before the Park Service implemented the management plan.”

“There was no status quo,” Boyle shot back. “There was just violation. There was no regulation. Anyone could drive on the beach. And there was no official Interim Strategy.”

Moving back to his argument, Kim said, “The public had plenty of information for evaluating the alternatives. But the standing of the plaintiff is still questionable. Does the plaintiff have any interest in protecting the species?”

The judge then asked if Kim had concluded his argument. Perhaps sensing the mood of the moment, Kim said he had and sat down.

Judge Boyle then recognized Julie Youngman of SELC, sitting at the defendants’ table, and urged her to be comprehensive in her remarks. She opened by referring to a seashore without the Park Service’s management plan.

“There would be nobody on the beach,” Boyle interjected. “It would be like the shutdown, the sequester, just chained up, without a plan.”

“We’ve heard about the harm of the plan” Youngman said, “but, in fact, the plan enables beach access.

“The Park Service properly identified all factors in beach usage, then used its discretion in creating the rule. Precedents in other parks were consulted. When Congress established the national park system, it’s clear that conservation of natural resources should predominate. The Organic Act that created the National Park Service, and subsequent clarifications, trump the Enabling Act. There is no basis for CHAPA’s claims based on the Enabling Act. Insufficient science? Insufficient economic analysis? There is overwhelming science to support the Park Service.

“The closures, the buffer sizes, ORV access were all carefully reviewed. Consider the FEIS No-Action Alternatives: either the Interim Strategy or the Consent Decree.”

“The Interim Strategy was more restrictive than the Consent Decree,” said Boyle.

“I don’t know about that,” Youngman said. “The legal status quo situation would be no driving on the beach.”

“Does the management plan take into account public safety,” Boyle asked, “the saving of lives? The seashore has been the scene of deaths and criminal prosecutions. Since the permits came in, there have been no deaths, fewer pedestrian injuries, and less criminal behavior.”

Youngman concluded her remarks by saying, “I don’t want to get into the adequacy of the science and the other analyses. I’ll say that there was an extraordinary volume of public comment. Some 16,000 people commented, with the majority supporting stricter species protection.” She sat down.

For little more than an hour, Judge Boyle had run the hearing much as he had run his series of status conferences, which presumably documented the success of the Park Service’s ORV management plan. There was little meaningful dialogue between the bench and the plaintiff’s and defendants’ bars. The judge’s questions were largely rhetorical, phased to countersink a point of view, not to elicit clarification.

It was as though Judge Boyle entered the courtroom with the same set of talking points that has become so familiar to those who have followed the seashore beach access issues for the past several years. Some think that His Honor’s judicial inclinations are clear.

Judge Boyle closed his notebook. “I will weigh the arguments heard today and rule as soon as possible. Court is recessed.”