Park Service offers sea turtle nest excavation programs

It’s official — sea turtle nesting on the Cape Hatteras National Seashore has set a record and the nests keep on coming.

According to today’s resources management report, 269 sea turtles have nested on the seashore — 15 more than the record 254 set in 2013.

And Britta Muiznieks, wildlife biologist and research coordinator for the seashore, said that three more nests have been added since data was collected for the report, which brings the total to 272.

Muiznieks said that, as is usually the case, most of the nests are by loggerheads but nine green turtles have nested to date. Also, according to the report, most of the nests — 185 — are on Hatteras Island with its 40 miles of seashore beach — with 79 on Ocracoke and five on Bodie Island.

“They’re still coming,” Muiznieks said. “We had four yesterday and one today. We expect many more to come.”

According to reports, sea turtle nesting is up everywhere along the coasts of North Carolina and other southeast states.

Muiznieks said biologists aren’t really sure exactly why this is. There could be many factors influencing the increase, including the warmer ocean water temperatures this summer.

“It could be that the conservation work that was done 20 or 30 years ago is beginning to pay off,” she said. It takes 25 or 30 years for female sea turtles to reach sexual maturity.

“Number have been slowly improving,” Muiznieks said, “but this year, they have just increased exponentially.”

Nests are also hatching earlier this year because of the warmer weather. About 26 nests have hatched thus far at the seashore.

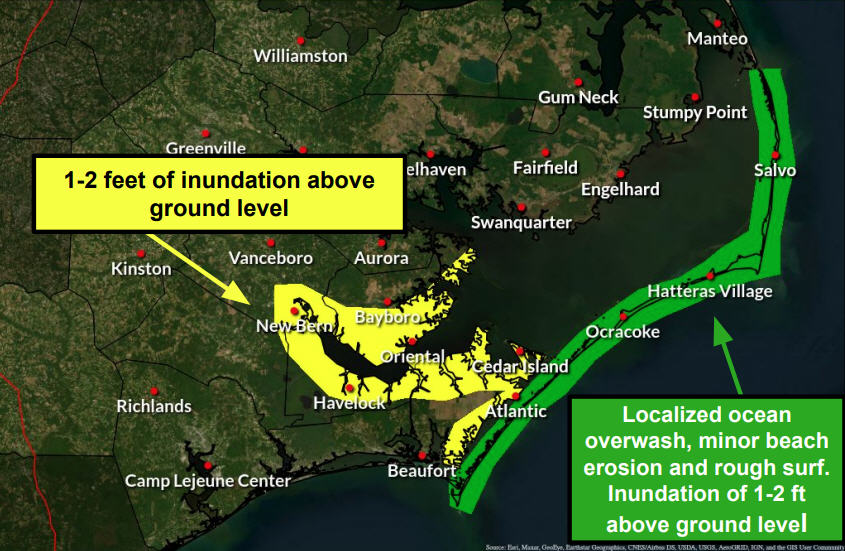

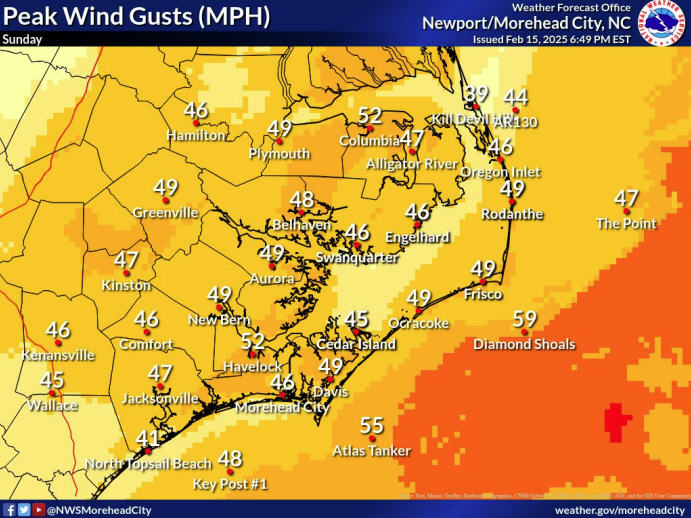

“Now we are keeping our fingers crossed that there are no storms,” she said.

Muiznieks supervises a seashore research project that aims to help biologists better predict when nests are about a hatch.

The project, called “Turtle Sense” was first conceived several years ago by Eric Kaplan, founder of the Hatteras Island Ocean Center in Hatteras village, who partnered with Nerds Without Borders to get the research underway. Biologists are placing electronic sensors in certain sea turtle nests that connect through a cable to a communication tower and send information to a project manager.

The theory is that there will be a flurry of activity from within the nest before the baby turtles hatch and “boil” out to make their way to the ocean. This usually happens after about 60 days of incubation, but the actual hatch date can vary, depending on such things as temperature and when the nest was laid.

Currently, the nests are “expanded” at 50 days to prepare for the hatch. The expansion of the resource protection closure can prohibit off-road vehicle and pedestrian access in certain areas, and the expansion can last for weeks if the hatch date is especially late.

Therefore, if park biologists could more accurately predict the exact hatch date, the times that beach areas are closed for nest hatching could be reduced.

This summer, the second full year of research, Muiznieks said she has placed the sensors in 28 nests. Eight have hatched, she said, and the information being provided is doing very well as far as predicting when a nest “boil” will occur.