How a trip to the beach turns into a sea turtle education

By JOY CRIST

By JOY CRIST

On a recent Monday afternoon at the Sandy Bay beach access – a spot where sunbathing and swimming are typically the order of the day – a group of beach-goers were surprised when they were approached by a gentleman in uniform who happened to be carrying around a sea turtle skull.

It was certainly an unusual encounter for the crowd at the semi-popular beach that’s located just north of Hatteras village, but within about five to 10 minutes, the man had drummed up about 35 to 40 people who followed him and his uniformed colleagues to the outskirts of a thin black barrier.

As it turns out, the man with the sea turtle skull was Brian Winnett of the National Park Service, and he and his three-person crew – which included lead biological science technician William Thompson – were there to excavate a recently hatched turtle nest.

The Cape Hatteras National Seashore is having a record-breaking year for sea turtle nests, and as more and more nests start to hatch, the National Park Service has set up an excavation program hotline at 252-475-9629 where the public can learn more about where and when an excavation will take place.

The excavation is an opportunity for people to see the discarded sea turtle eggs up-close, take a peek at the tiny tracks that trickle into the ocean wash, and sometimes even see a live hatchling or two which — for whatever reason — were unable to make the initial run to the ocean.

When it’s at an area that’s easy to access – like the old Cape Hatteras Lighthouse site or another beach with ample public parking – the excavation is publically announced so that people can stop by and get an insider’s perspective.

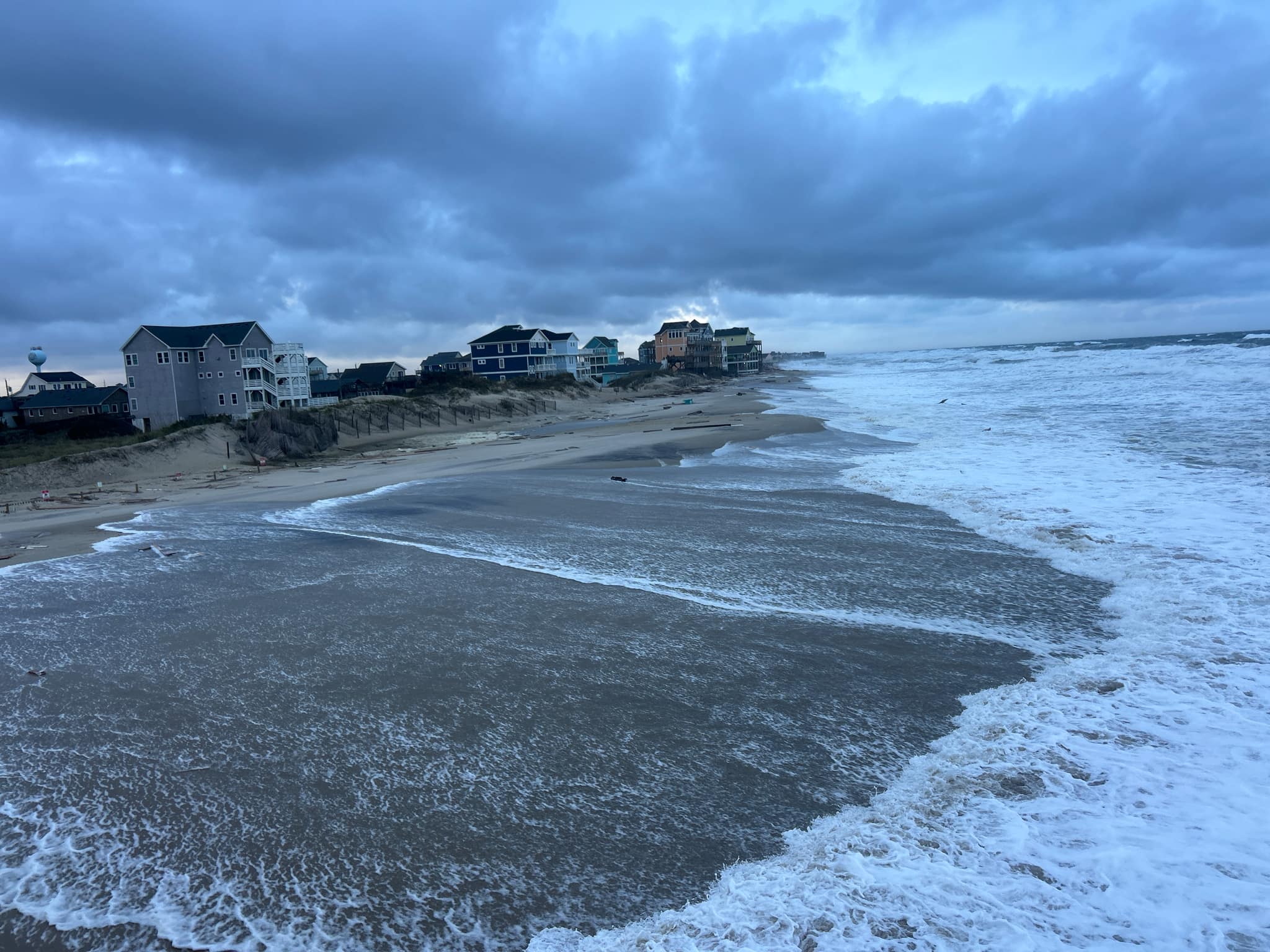

But when it’s in a slightly more remote location, like this particular beach between Frisco and Hatteras, it’s simply a matter of being in the right place at the right time.

“We try to regularly do the formal [public excavations],” says Winnett, “but so far they’ve been limited to day use areas – like the Old Lighthouse Beach or Coquina Beach…. But if we have the opportunity, and people are available on the beach 15 minutes or so before we do the excavation, we try to drum up interest.”

The ensuing experience is an impromptu presentation that sometimes, like on this afternoon, tends to draw quite the crowd, and that starts with the NPS rangers approaching people on the beach to tell them that a potential opportunity to see sea turtle eggs – and maybe even live sea turtles – is just a few minutes and a few yards away.

“Basically we go around, and let people on the beach know what’s happening. That way, people can see first-hand how the Park Service operates, and see what this is all about,” says Winnett, indicating the small roped-off closure that’s immediately torn down after the excavation ends. “It gives us an opportunity to do a little talk about what we’re doing, and how we protect the sea turtles. And a lot of times, there are live hatchlings, and that’s an opportunity for people to see

them up-close. This is the first one out of a handful [of nests] that I’ve been to where there weren’t live hatchlings.”

William Thompson works in the sand as he explains the nesting process to an engaged crowd who have cell phone cameras in hand. Within 30 minutes or so, the nest has been fully examined, and although here are no live hatchlings present, there are a few unfertilized eggs that Thompson breaks open and shows to the crowd. Several have been semi-cooked due to the heat, and while there’s a slight disappointment that no live hatchlings were uncovered – which would have been transferred to the red cooler container that the NPS crew has on hand – the overall story of the sea turtles, and the first-hand glimpse of turtle eggs, is nothing short of impressive.

Frank Welles, Freve Pace, and Olie Bedell – three volunteers who sat at the nesting site along with Amy Metting-Galetar and a few other volunteers – were also present for the excavation, and affirmed that seeing a couple of live hatchlings after the hatch was always a possibility, but never a guarantee.

“Often there’s live babies in there, even though we didn’t have any today,” says Welles, indicating the former nest site. “At least half of the time there’s one, two, or even three babies [still present] – and a couple of times, the number has been up in the teens.”

“We all wanted to see a couple of [live hatchlings], but we’re also happy that we didn’t see any,” says Pace.

“It’s the same as when we have to handle the turtles during the hatching,” explains Welles. “We hate to handle them because you really don’t want to have to be involved, but at the same time, we also love to do it because we actually have a chance to pick them up.”

The remnants of this particular nest shows that this nest resulted in 115 hatched eggs out of 127 total. It included two deceased hatchlings, as well as five unfertilized eggs. This info is written down in the log book, as well as shared with the crowd on site.

“So it’s about 90 percent [success rate],” says Thompson to the crowd, “And that’s a pretty good number.”

After the 30-minute or so presentation – which includes the actual excavation of the nest – the NPS crew answers questions and chats with people for a few minutes, and then the crowd goes back to their regularly scheduled afternoon of enjoying the beach, while the NPS staff members take down the former turtle nest enclosure and leave.

Ten minutes after the NPS crew departs, a couple of new groups arrive on the beach and set up umbrellas and chairs on the now vacant spot along the shoreline. And any indications that the site was a sea turtle nest enclosure just an hour before – with the exception of the still subtle hatchling tracks along the beach – have completely disappeared.

But the folks who were at the scene, and who were lured by the uniformed crew to see what was happening, won’t soon forget this otherwise nondescript Monday afternoon.

“This is really incredible,” says one beach-goer from Virginia. “I didn’t expect to see this when we went to the beach today!”

Volunteers are always needed to help with the sea turtle nest sitting, and volunteer opportunities will come in the fall, as well as for the 2017 summer season.

And in the meantime, visitors should keep an eye out for crowds gathered along the distinctive black barriers along the beach – chances are, it’s another impromptu sea turtle presentation that just happens to coincide with a beach trip.

“By hearing about the sea turtles, and seeing this first-hand, [the public] can appreciate the struggle – how tough it is for them to reach adulthood, and then come back to the beach to lay eggs,” says Winnett. “It’s definitely a numbers game.”