No easy answers yet for maintaining inlets

North Carolina lawmakers will not receive a completed final report on the Coastal Resources Commission’s inlet management study by year’s end.

“We are not going to know everything by final report time,” CRC Chairman Frank Gorham said last week following the last of a series of public meetings held to discuss inlet issues. “We have a lot to do, and I don’t have a problem telling the General Assembly or the governor we’re not finished.”

Maybe 40 percent to half of the report will actually be complete and ready for submission by the Dec. 31 deadline, he said.

The study, born out of a legislative directive to the state Division of Coastal Management to study land adjacent to the mouth of the Cape Fear River, was outlined last year by Gorham in a memo to CRC members. It is tackling a series of highly complex issues related to inlets.

Its results will be the basis for policy decisions that will affect dredging, channel realignment projects, development standards for inlet areas, inlet erosion rates, terminal groins and how beach communities will be allowed to respond to emergencies that may require bulldozing sand or sandbagging to protect homes, businesses and infrastructure such as septic tanks and roads.

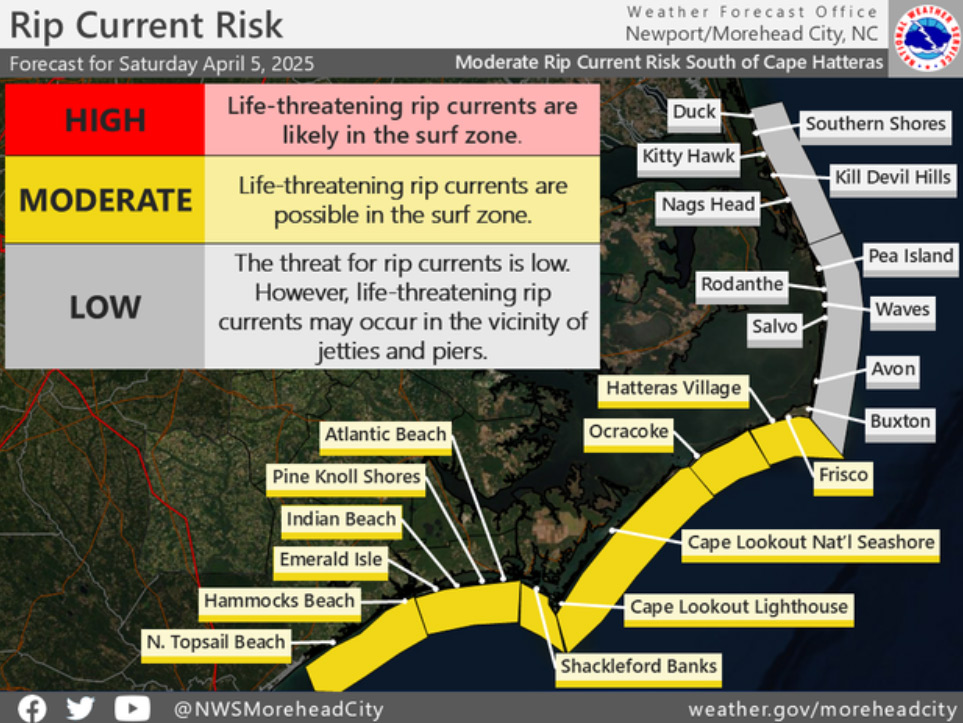

North Carolina’s coast has 19 inlets. Twelve are “developed inlets,” meaning they are lined by homes, condos, hotels, and other businesses.

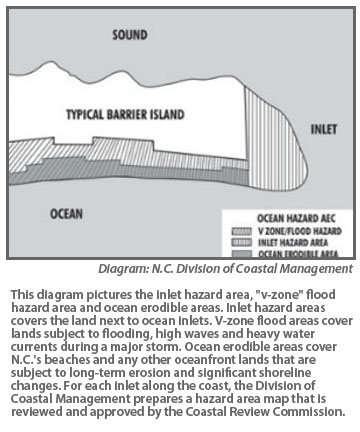

Inlets are dynamic geological bodies that generally ebb and flow with the tide or migrate altogether. When these inlets move they sometimes endanger beach structures, threatening to feed them to an encroaching sea.

Beach towns are persistently trying to maintain and manage the inlets not only to protect homes and businesses, but because inlets play a significant economic role.

The value of keeping the inlets navigable and the costs local governments are incurring to maintain them has been an overarching theme throughout the coastal management-hosted meetings.

“Federal dollars are going away so we have to be more efficient with the local dollars we have,” Gorham said. “We need to have a plan as if we’re not getting federal dollars. We also need to make our dredge programs more efficient. I think we have a real breakdown between the core funding issue and coastal communities that have worried about how they’re going to fund their dredging projects.”

Local beach town officials, engineers and shoreline and waterway associations are asking the CRC to help them establish guidelines that will allow them to affordably maintain these inlets, particularly the state’s five shallow draft inlets, which do not receive the same amount of federal resources as larger, deeper, commercial navigation channels.

“It seems like we’re always in a defensive mode,” Carolina Beach Mayor Dan Wilcox said. “It seems like we’re always in a posture where we react instead of anticipate. Our main concern right now is keeping our inlet open.”

Carolina Beach Inlet is dredged to a depth of about eight feet. Persistent shoaling routinely and quickly re-clogs the inlet, making it practically unnavigable.

This is a similar problem in New Topsail Inlet, another shallow-draft waterway heavily used by commercial fishermen, charter boats, locals and tourists to quickly access the Atlantic.

Both Carolina Beach and Topsail Beach have been examining ways to dredge deeper and more often. It’s a process much easier said than done for a variety of reasons, the first of which is the lack of federal money available to sustain routine dredging of these inlets.

The Army Corps of Engineers has three shallow draft inlet dredges. Inlet dredging is limited to six months out of the year so as not to interfere with turtle nesting season. As a result, beach towns end up competing for dredges within a narrow window of time.

“We’re doomed basically if we don’t come up with a plan B,” said Dennis Barbour, a member of the N.C. Beach, Inlet and Waterway Association. “We need the Division of Coastal Management and the Coastal Resources Commission’s help.”

That will take some political posturing.

“The coast represents 14 percent of the people in North Carolina,” Gorham said. “I don’t think we even have 14 percent political clout in North Carolina. We are not appreciated in Raleigh.”

Beach towns, coastal counties and groups advocating shoreline and waterway protection need to band together and do a better job of touting the coasts’ economic benefits to the state, he said.

Inlets are an integral part of that discussion because they are responsible for bringing millions of dollars to the local and state economies.

They are also individually unique waterways that each need its own management scheme, said Bill Cleary, a retired geology professor and member of the CRC’s Science Panel on Coastal Hazards.

Channel realignment, terminal groins, sand bypassing – all may be effective in managing different inlets, he said. New Topsail Inlet, for example, is not a candidate for a terminal groin or relocation because it has migrated about 5,700 feet, Cleary said.

Shallotte Inlet oscillates within a very narrow zone, making it a prime candidate for a terminal groin, he said. A handful of beach communities — Figure Eight Island, Ocean Isle Beach, Bald Head Island and Holden Beach — are currently seeking state permits to build terminal groins.

The state prohibited the construction of terminal groins as erosion-control devices on the beach until 2011 when the legislature allowed four to be built.

The designation “inlet hazard area” in state rules is reserved for areas around inlets because they are particularly susceptible to erosion. The designation is crucial because it establishes setbacks and building restrictions designed to protect the public’s safety and environmentally sensitive areas.

The science panel was asked in 2005 to draft a report on inlet hazard areas, zones especially vulnerable to erosion, flooding and other adverse effects of sand, wind and water because of their proximity to inlets. At the time, it was recommended that the panel complete the development methods to designate these zones. That report has yet to be published, said Spencer Rogers, a member of the science panel and coastal engineer with North Carolina Sea Grant.

The CRC in February made the controversial decision to remove what was formerly Mad Inlet, which ran alongside Sunset Beach in Brunswick County, from an inlet-hazard designation. Based on a recommendation from the science panel, the CRC deemed the inlet, which last closed in the mid-1990s, was no longer, by definition, an inlet.

The science panel also suggested that the CRC examine “temporary” inlets, those prone to reopening during a storm, in its management study.

“We probably need to look at that,” Gorham said. “The question is do we have the same rules for those areas that might be prone to opening. I’m not comfortable saying we’re going to have the same tough rules for those areas that we have for inlet hazard areas.”

Where to Comment

The N.C. Division of Coastal Management is accepting written comments on its inlet-management study through April 15. The study’s final draft findings are due July 31.

Written comments can be sent to Matt Slagel, 400 Commerce Ave., Morehead City, 28557, or e-mailed to him at matthew.slagel@ncdenr.gov.

(This story is provided courtesy of Coastal Review Online, the coastal news and features service of the N.C. Coastal Federation. You can read other stories about the North Carolina coast at www.nccoast.org.)