Buxton Navy base’s reminders not just petroleum in soils

Petroleum spilled and partially cleaned up at a long-abandoned U.S. Navy base at Cape Hatteras recently reemerged in clumps of peat soil after a storm. Last month, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stepped up to take responsibility for the cleanup, even though its source is technically uncertain.

But the diesel smell and oily mudballs, now temporarily reburied, are only one of the wretched souvenirs left behind on the Cape Hatteras National Seashore beach by the Navy and later, the Coast Guard, including chunks of building debris, metal shards from deteriorated jetties and possibly other soil contaminants.

“Looking at the historical evidence and knowing that the Navy had a release, we’ve decided that we are going to address any petroleum contamination that may still be present,” Carl Dokter, manager of the Corps’ Formerly Used Defense Sites, or FUDS, program based in Savannah, told Coastal Review.

The Corps responds to environmental liabilities at sites that were owned, operated or controlled by the U.S. Department of Defense before Oct. 17, 1986, he said. The Navy had operated a submarine surveillance operation in Buxton under a special-use permit from the National Park Service from 1956 to 1982. The Coast Guard acquired the site, near the original location of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, in 1986, operating as Group Cape Hatteras until the base relocated in 2005 to Fort Macon in Carteret County.

According to a 1999 Corps site assessment, the state Department of Natural and Environmental Resources had issued a notice of violation to the Buxton facility in 1997, citing at the time groundwater samples containing chemicals 1,2,3,4 trimethylbenzene and naphthalene.

After discovering that the petroleum storage tanks on the base had apparently leaked, Dokter said, the Corps in the early 2000s removed the tanks and a significant portion of contaminated soil.

The smell after the storm

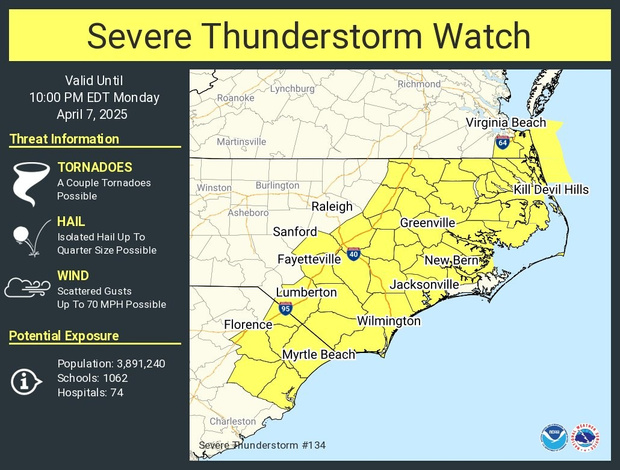

Cape Hatteras National Seashore Superintendent Dave Hallac got a call on Sept. 1, after Tropical Storm Idalia, from a Hatteras Island resident concerning a strong diesel smell coming from the old Navy base, as well as a sheen in the ocean waters.

When staff arrived at the site, they didn’t see any sheen on the water, but they did note a slight smell of diesel, Hallac told Coastal Review. After Hallac reported the problem, Coast Guard members from Sector North Carolina came to the site and took soil samples that showed contamination from petroleum. The park service then closed that section of beach, which remains closed.

Hallac said the odor had followed strong swells from the offshore storms that caused erosion and uncovered the polluted soil. But about two weeks later, the situation worsened, with surfers in the area reporting headaches and rashes. On Sept. 26, the Dare County Department of Health and Human Services and other agencies issued a public alert to avoid swimming, fishing or wading in the area. Big clumps of oily peat soil, also called mudballs, were scattered over the beach.

“It was obvious that the odors were coming from those soils,” Hallac said. “I mean, it was very strong.”

The Coast Guard then made another visit and took more samples, finding “weathered light fuel oil, a small amount of lubricating oil, petroleum hydrocarbons, and non-petroleum contamination,” according to the county’s news release.

“Totally coincidentally,” Hallac added, the Army Corps happened to be at the site when the odor was strongest, doing the groundwater remediation it has been conducting here on and off for years. The Corps also took a soil sample, which confirmed petroleum contamination.

Dokter, with the Corps, said that the agency has been addressing residual contamination in groundwater since it removed the tanks years ago. The Savannah district has been working with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality to reduce the amount of methylnapthalene to acceptable levels.

“We have a series of injection wells and monitoring wells and we have been injecting a proprietary product … (that) binds with the petroleum and petroleum byproducts for neutralizing, but it doesn’t happen quickly,” he said. The last injection was done about 18 months ago, he added, and the Corps has continued sampling and monitoring on a quarterly basis. After the results are below regulatory levels, the site will be closed.

When the mudballs started washing up, it was clear that the petroleum contamination in the area was broader than previously understood. But Dokter said certainty as to its providence was close to impossible, especially since the oily peat clumps had already been reburied, and the beach has likely eroded 150 feet or more in recent years.

“We briefly considered trying to do what we call fingerprinting to establish, is it older petroleum or is it ’90s or later-type petroleum?” he said. “And there’s a marker that can tell you the difference. The problem is saltwater complicates everything, and the results are likely to be inconclusive if we even managed to get a sample of the (peat) product.”

Coordinated effort to determine corrective actions

The Savannah district announced Oct. 23 its intention to coordinate efforts with NCDEQ to determine corrective actions.

“While tremendous progress in technologies and techniques addressing environmental contamination have been made throughout the years, currently, there isn’t a fail-proof method that will provide a 100 percent certainty all environmental concerns are discovered and can be completely addressed,” the statement said. “The Corps does everything it can to ensure when its work is complete, human health and the environment are protected.”

Meanwhile, according to Hallac, the Coast Guard is in the process of implementing a Phase II environmental assessment of potential contaminants at the site.

The Coast Guard has not responded to multiple phone calls and emails from Coastal Review seeking information.

According to an online report, the Coast Guard was scheduled to start a $500,000 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act, or CERCLA, investigation at the old U.S. Coast Guard Group Cape Hatteras site around June 15. “The contractor shall provide professional architectural and engineering services to perform continued CERCLA investigation in order to determine the extent of groundwater and soil contamination,” the posting said. “The contractor shall provide recommendations for additional remediation where applicable at the USCG Group Cape Hatteras (decommissioned) in Buxton, NC.”

In a Coastal Review report published July 1, 2013, a Coast Guard environmental engineer said that preliminary testing at the Buxton site detected evidence of chemicals that include benzanthracene, benzopyrene, chlordane, dieldrin, and endrin, as well as traces of heavy metals arsenic, chromium and mercury.

At the time, the Coast Guard was seeking $200,000 for remediation costs. No further information about the proposed cleanup has been provided.

Visible remnants

Far more visible remnants of the military’s former presence at Cape Hatteras’ oceanfront have become an increasingly obnoxious eyesore and hazard to beachgoers and surfers, including sharp shards from three concrete and steel groins the Navy installed in 1970 to stem beach erosion.

Although there had been previous discussions about repairing or removing the structures, which locals call jetties, no agency claimed responsibility, and they were left to further deteriorate after the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was moved from the beach in 1999.

“There’s stuff that’s sticking out of the sand now,” said Carol Busbey, an owner of Natural Art Surf Shop in Buxton.

The “first jetty,” a favorite surf spot at Lighthouse Beach, has fallen apart to the extent that Busbey now has a piece of it standing in her shop’s parking lot.

“We’re actually going to sink it into the ground,” she said. “People have been cut by it. I wish they would do something about it. The surf break isn’t there anyway.”

Busbey blames the jetties’ demise and accompanying changes in the sandbar for ruining surfing at the spot. “It changed it completely,” she said. “It used to be such a great surf break. But the beach’s reputation keeps surfers coming anyway to catch what they can. Unfortunately, sometimes the jetties can be dangerous.

“The third jetty — the north jetty — it’s got horrible spikes sticking up,” she said. “At high tide, you can’t see those pieces sticking up.”

In addition to litter on the beach from the oil-soaked peat clumps, which probably originated from the salt marsh, there are also chunks of debris from the old bases being exposed by erosion, much of it since September.

“There is a historic wastewater tank that is essentially on the beach — the foundation of it — that has been exposed,” Hallac said. “The building upon which the listening cables that we believe the Navy used, the foundation of that building, pipes leading into that building, chunks of concrete — and I mean very large chunks of concrete — all of that is now exposed, septic drain field pipes, PVC pipes.

“It’s to the point where it’s not safe,” he said. “There’s too much concrete, rebar, metal pipes along the beach section here that’s it’s really not safe to walk up and down the beach.”

Hallac has been discussing his concerns with both the Coast Guard and the Corps. He said he will likely reach out to the Navy soon. But, he said, the Corps is not optimistic that it could help with the problem.

As it is, the Corps has plenty of concerns with Buxton on its plate. After its risk assessment on the petroleum in the peat is completed, Dokter said the Corps will consult with NCDEQ about how to move forward, since it’s yet to be determined whether it’s even possible to remove a layer of contaminated peat soil.

“We haven’t really established a feasible way to do that,” he said. “Essentially, to remove a subsurface layer involves some level of dewatering. It’s not impossible to dewater a beach, but the costs would be astronomical.

“This is a challenge,” Dokter added. “We’ve included some of our chemists, geologists, and environmental engineers, what we call our center of expertise within the Corps, because it’s a little more challenging of a problem than my typical project sites.”