20 years ago a runaway dredge tore a hole in the Bonner Bridge, and islanders and visitors relied on temporary ferries for months…WITH SLIDE SHOW

BY CATHERINE KOZAK

BY CATHERINE KOZAK

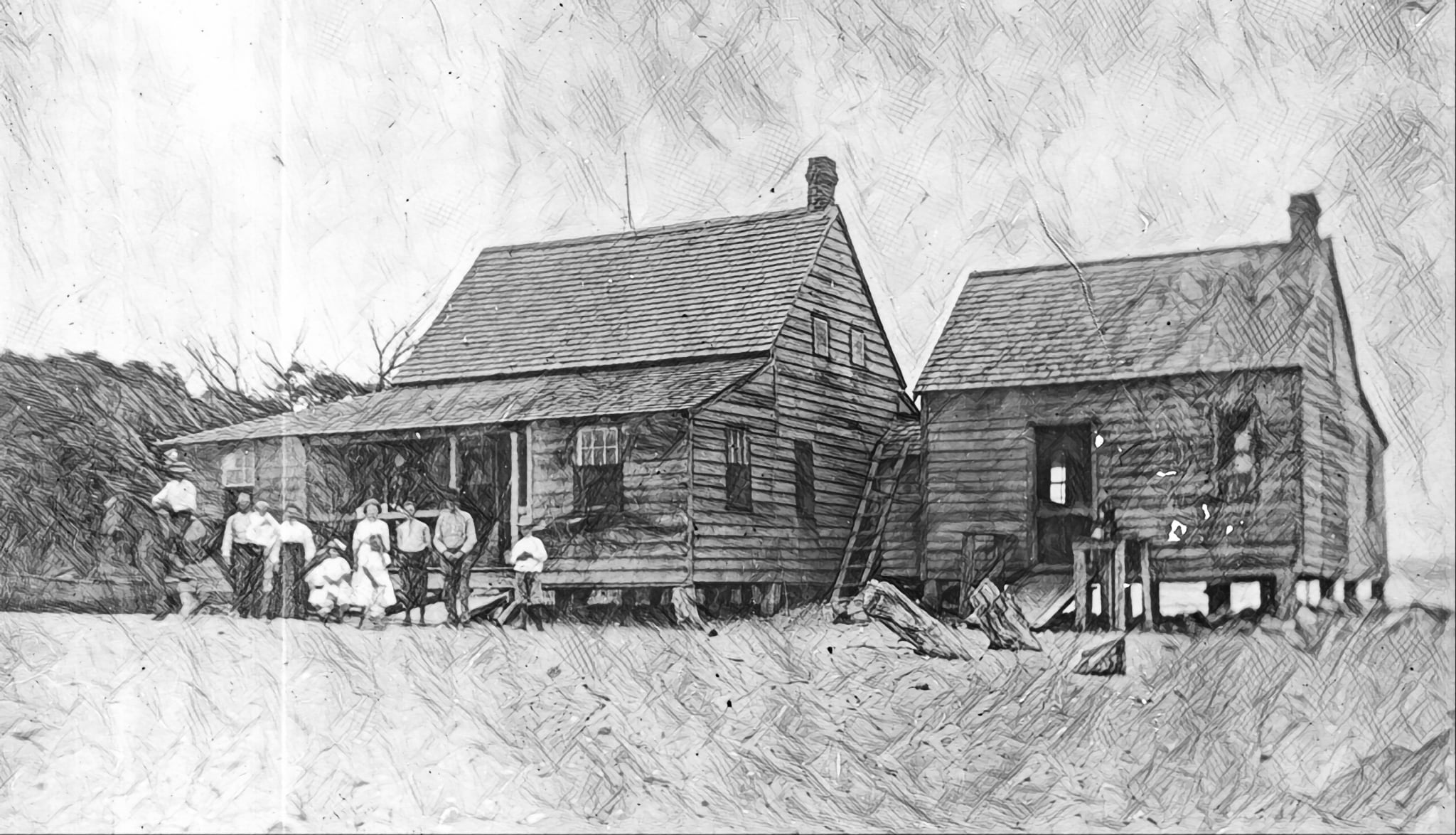

A hard nor’easter was pounding the Outer Banks as Mickey Baker and Carmie Prete hustled home to Ocracoke Island that October night 20 years ago, intent on beating the heavy weather before Highway 12 flooded. As they crossed the Herbert C. Bonner Bridge, they spied something odd looming in the darkness, just off the span.

“We looked to the left, and there was the dredge,” Baker recalled in an interview last week. “Right there — the crane and everything.”

The equipment’s close proximity was remarkable enough to comment on, she said, but not ominous enough to interrupt their hurried journey.

It wasn’t until the next morning that the women, then owners of the Island Ragpicker, learned that the 130-foot high dredge Northerly Island slammed into the Bonner Bridge at 1:28 a.m., causing a 370-foot section to collapse about an hour later into the swirling Oregon Inlet. With it went the telephone and electric power lines that ran under the bridge.

The storm-tossed dredge, working earlier on the east side of the bridge, had lost its moorings at about 10:30 p.m. Dragging its anchors, straining against wind gusts up to 90 mph, the 200-foot vessel lumbered intractably toward the bridge. At 1 a.m., the captain notified the Coast Guard. Police rushed in to stop traffic. Moments before the dredge rammed the span, the last vehicle on the bridge had reached safety. Miraculously, no one was injured.

On Oct. 26, 1990, Hatteras and Ocracoke islands lost their only land link to the mainland. It would be 3 1/2 months before they got it back. In between, they made-do with unreliable ferry transportation and Outer Banks resourcefulness.

Those months serve as glowing examples of the resilience and goodness of islanders, and how government response can be capable and efficient.

Those months also proved how critical a bridge over Oregon Inlet is to Dare County commerce and the islanders’ lifestyle and quality of life — and why many are appalled at suggestions that ferries could be used instead of replacing the aged Bonner Bridge.

“It’s just not a viable solution,” said Tommie Gray, a Hatteras resident and former information technology director for Dare County, who often took the hour and a half ferry ride over the inlet.

“It’s just ridiculous.”

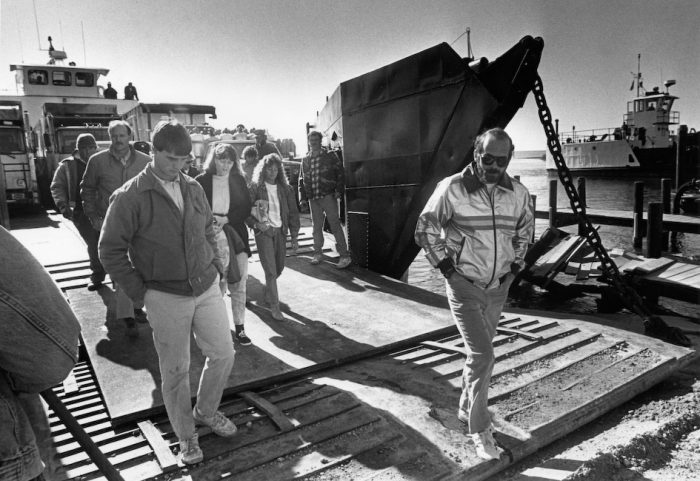

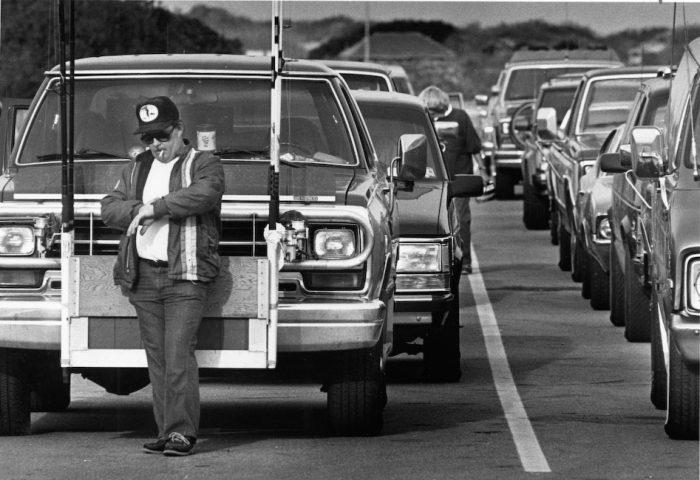

When the bridge collapsed, it wasn’t only the year-round island residents — about 5,000 on Hatteras and 650 on Ocracoke —who found themselves forced to cope. Thousands of visitors were thrust from vacation bliss into being virtual prisoners of their vehicles. Emergency orders entrapped them for entire days and nights — as much as 36 to 48 hours — in long evacuation lines. The only exit initially from Hatteras was to take the Hatteras Inlet ferry to Ocracoke, make the 13-mile trip to Ocracoke village, and then ferries running to Cedar Island and Swan Quarter on the mainland.

Of course, the visitors leaving Hatteras for the mainland ferries were vying for space with the tourists who were trapped in Ocracoke.

Back-ups of vehicles lined Highway12 on Ocracoke, stretching about 13 miles from the Hatteras Inlet ferry dock to the edge of the village. Every five hours or so, another ferry would load up and leave.

Confronted with an invasion of hungry people, Ocracokers leaped to help. Residents collected their canned soups, and tossed the contents together into big cauldrons borrowed from local restaurants. Then, driving down the line, they served trapped visitors the hot concoction in paper cups from the back of their pickup trucks.

“One of the best memories I have is a couple of tourists saying, ‘You people on Ocracoke make the best soup,’” Baker said, chuckling.

A dozen or more islanders went up and down the line — at least one person was required to stay in the vehicle — and asked what supplies the occupants needed, Baker recalled. The necessities were then purchased on credit by the volunteer at the local grocery store. The cost was scribbled on the bag and it was delivered to the vehicle occupant, who would then pay for it.

“They needed everything from Tampax to baby food,” she said. “We were the drive-up waitresses.”

At some point, the Red Cross showed up, supplying peanut butter sandwiches and bologna sandwiches. Porta-potties were brought in. The school auditorium was opened up for the frail, young and old.

“We were feeding the people and they were saying, ‘These are the best sandwiches we have ever had,” said Baker, who with Prete now owns Mermaid’s Folly on Ocracoke.

“Oh, it was a time!”

For years, people who were in the line would stop in the store to reacquaint. Baker heard later that one group of evacuees bonded so closely during the ordeal, that after leaving the ferry, they had driven in an unbroken line all the way to Morehead City.

“I just thought that was beautiful,” she said.

Soon the National Guard arrived, bringing mounds of blankets and sleeping bags. Some people opened up their mobile trailers and created ad-hoc day care centers for the car-bound children. Others shared drinks and played music outside their vehicles. Many evacuees made the rounds, communing as if the vehicles were a stretched-out line of bar stools.

“The reaction from the people here toward all the stranded people was just above and beyond,” said Ruth Fordon, today the editor of the Ocracoke Observer. “It was just pretty remarkable to see.”

Kathleen O’Neal, owner of Island Artworks, was then employed by the state Ferry Division and assigned to directing traffic onto the boats that were taking visitors off Hatteras. Everyone located south of Oregon Inlet had been ordered to evacuate, and Hatteras was the funnel.

O’Neal remembers the line of vehicles encircling the parking lot at the ferry dock, up the highway, through the village, and all the way to the campground. Working 16-hour shifts, living off candy bars, O’Neal said she wore a heavy down parka to stay warm in the abnormally cold temperatures.

“I was just so tired,” she said. “To me, it was worse than any hurricane evacuation ever was. People in the cars were angry they couldn’t get off. A lot of people were making up emergencies.”

Then-Dare County Sheriff Bert Austin , said that old World War II landing craft were brought in initially to provide emergency transportation across Oregon Inlet for heavy equipment and vendor trucks. The state, meanwhile, hurried to build emergency ferry ramps at the inlet.

“It was unbelievable,” he said. “The Department of Transportation did an outstanding job.”

Austin, 79, said that he remembers that there were some angry people, but overall there were no significant law enforcement issues.

“Most everybody was understanding,” he said, adding, “but you always have a few.”

The villages of Avon, Buxton, Frisco, and Hatteras had water, although they were advised to conserve it in case of fire or other emergencies. The residents of Rodanthe, Waves, and Salvo did not have water, since electricity was required to power the water pumps.

Electricity was very limited until emergency generators were delivered from emergency officials and the North Carolina Electric Membership Corp. in Raleigh. Electric service was restored to the island with these generators on Monday, Oct. 29. However, for a time, residents of Buxton, Frisco, and Avon had electricity on a six-hour rotating basis. It also took days to reroute phone service. Special arrangements were made for delivery of mail and medicines.

Grocery trucks were able to get through first on World War II-era landing craft and then on the ferries, so supplies for island-locked people were adequate, said Allen Burrus, owner of Burrus Red & White Supermarket in Hatteras, joking that beer trucks were given priority.

Burrus, who is currently the vice-chairman of the Dare County Board of Commisioners, was at that time a member of the county Board of Education. In that role, he often had to take the sometimes arduous voyage across the inlet. Ferries ran through the night, weather permitting. But with the unpredictable conditions, even buses of student athletes had to wait out the weather on the ferry.

“People got stranded,” he recalled, “and we just hunkered down and did it.”

On the Oregon Inlet side, the Ferry Division assigned Clay Harris as nighttime port captain, overseeing operations from shore. Harris said it took about 30 minutes to unload the”worn-out and tired” landing craft that operated until the ferry ramps were built in an impressive seven days.

Then a 24-year-old Avon resident, Harris said he worked 23 days without a break, sleeping at a Manteo hotel, until management told him he needed to take a break. Two single-wide trailers were stationed onsite to serve breakfast and lunch to workers.

Three ferries would run around the clock in the inlet, each transporting about 30 cars in about 60 minutes —- in perfect weather.

“It would get so foggy that sometimes the boat had to stop in transit and we had to idle it,” said Harris, currently the ferry division’s chief engineer at Hatteras.

“There were frequent groundings in the fog, especially at night, because the channel was very narrow. And the current was strong. We were lucky — most of our boats were new at the time.”

Ferries had to take a circuitous W-shaped route from the fishing center into Walter Slough, Harris recalled. They would then have to make a sharp turn at Hell’s Gate toward the bridge, make another dogleg turn toward Davis Slough, then head south to the other side.

And the Hatteras -class ferries could not operate in the 6.5-mile channel if winds exceeded 35 mph, he said.

On Thanksgiving weekend, Harris remembers traffic backed up about three miles from the Oregon Inlet Fishing Center all the way to Whalebone Junction, with the parking lot completely filled with vehicles. It took about six to eight hours for those in the back to reach the front of the line.

Several times, people threatened Harris, including one angry man who said he would “whip my ass,” he said. Harris sent him inside to see Herbert Jackson, the no-nonsense day port captain.

“The guy came out with his head down and went back to his car.”

On other occasions, Harris said that the police had to be called in. And he said that trouble makers included some tipsy locals who were upset about not being able to get back to the island fast enough.

Rough spots aside, Harris said, the emergency operation was humming along after the first month. According to a February, 1991 article in The Virginian-Pilot, a total of five ferries and one landing craft carried 85,000 vehicles starting Nov. 7, with 80 of the ferry division’s 140 staff stationed at Oregon Inlet.

“We had quite a few who didn’t mind the trip and they went back and forth regularly,” Harris said about the islanders.

That’s not to say a ferry system in Oregon Inlet could replace the bridge, he said. New ferry ramps have since been built at Stumpy Point and Rodanthe for emergency service, and the 1 hour 20 minute trip was made successfully by several ferries for a few days after last November’s northeaster.

But, with the island’s growth and development, it could never serve the community adequately in the busier months, when thousands of people cross the span daily.

“I don’t know how they’d do it,” Harris said. “I really don’t.”

GeeGee Rosell, a Frisco resident who had come over the bridge an hour before it was hit, had to have medicine shipped in for her sick cat. Although she did not leave the island until after the bridge was restored, her parents came to visit from West Virginia just for the adventure of riding the ferry.

Rosell, owner of Buxton Village Books, said that the community is not quite the same as it was in 1990. Back then, people were used to squirreling away money to use in a crisis, rather than depending on credit. Things were less expensive, most everyone knew each other, and everyone shared and pitched in to do what was required.

“I don’t think,” she said, “we would fare as well now as we did then.”

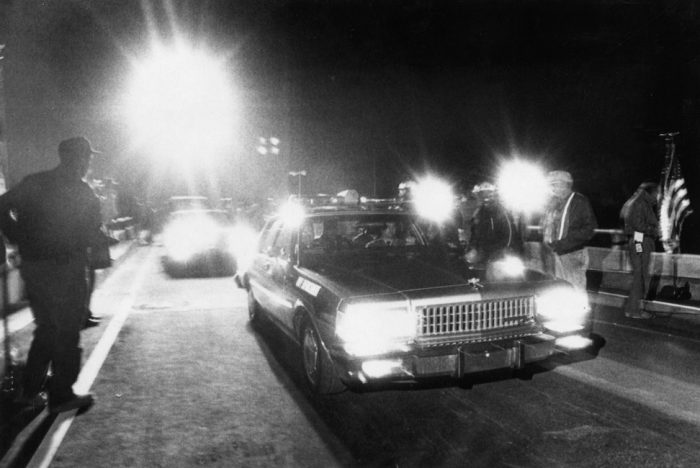

It took 110 days and about $5.6 million to repair the bridge, which re-opened two weeks ahead of schedule on the evening of Feb. 12.

Dredge captain William O. Cliett of Savannah, Ga., was found not guilty of Coast Guard charges of negligence and misconduct.

Hatteras Islanders suffered an economic toll, losing much of the fall fishing and Thanksgiving business because most visitors didn’t want to wait in line for hours to get on and off the temporary ferries.

But two decades later, a final plan to replace the wounded and patched 47-year old Bonner Bridge has still not been approved.

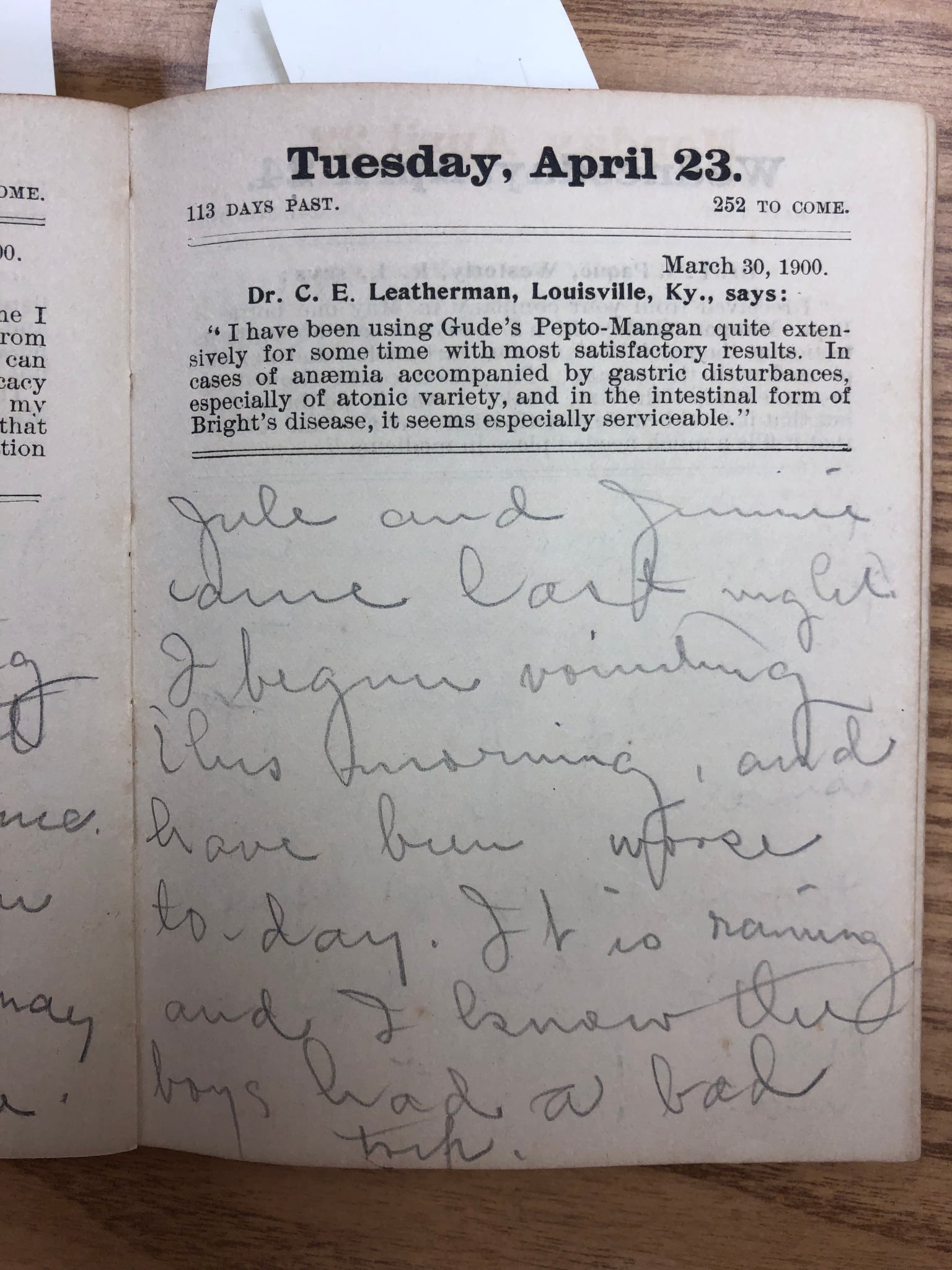

Click here to see the album that Ocracokers made and filled with letters from the thousands of stranded visitors they aided in the days after Oct. 26, 1990, when all of Hatteras and Ocracoke visitors – thousands of them — had to leave by ferry from Ocracoke village to the mainland.