In the years of discussion of off-road vehicle rulemaking for the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, have you ever heard anyone utter the words, ?seabeach amaranth??

Have you heard anyone talk about seabeach amaranth at a public meeting, public forum, public comment session, or negotiated rulemaking committee meeting?

Have you seen anyone railing against protections for seabeach amaranth on discussion boards or blogs or in letters to the editor of a publication?

Chances are very good that you have not. And there is also a chance you never heard of seabeach amaranth, don?t know what it is, and don?t know why we should care about it.

As far as I can tell, not even the Southern Environmental Law Center has had a word to say about seabeach amaranth on its website or in its media releases.

Seabeach amaranth just doesn?t get any respect, despite the fact it is one of three federally protected species that the Park Service?s Final Environmental Impact Statement aims to protect from harm ? by people and, especially, of course, from ORVs.

The other two ? piping plovers and sea turtles ? get pages and pages and pages in the FEIS. Seabeach amaranth is almost a footnote.

You may well have seen piping plovers and sea turtles at the seashore, but you probably haven?t seen seabeach amaranth. I?ve been visiting here for 35 years and have lived here for 20 years, and as far as I know, I have never laid eyes on seabeach amaranth.

You may well have seen piping plovers and sea turtles at the seashore, but you probably haven?t seen seabeach amaranth. I?ve been visiting here for 35 years and have lived here for 20 years, and as far as I know, I have never laid eyes on seabeach amaranth.

In fact, for the past five years, apparently nobody has laid eyes on the plant. There have been no plants here. The last two reported at the seashore were found in 2005.

But, the plant might return some day, so it gets protection from the National Park Service in its Final Environmental Impact Statement for ORV rulemaking at the seashore.

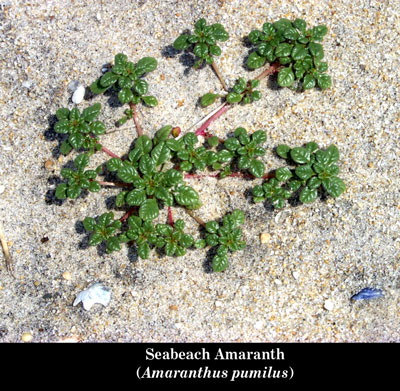

Seabeach amaranth is a plant that is native to barrier-island beaches along the U.S. Atlantic Coast. Its scientific name is Amaranthus pumilus.

It is a low-growing annual with stems that trail along the ground but do not root. The stems are pinkish-red and fleshy and grow to 4-24 inches. Spinach-green leaves are thick, oval-shaped with a slightly notched or indented tip and are clustered toward the tip of the stem. Flowers grow in clusters at nodes where leaves attach to the main stalk. The fruit is small, 0.16-0.20 of an inch long, and smooth. Seeds are shiny black, about one-tenth of an inch long. The seeds are thought to be viable for a long time.

The plant initially forms a small unbranched sprig but branches profusely into a clump, often 10-12 inches across and consisting of 5-20 branches. Occasionally a clump may grow to be 3 feet or more across with 100 or more branches.

Germination of the plant occurs from April into July and flowering and fruiting occur from July until first frost, peaking in September.

The plant occupies a ?fairly narrow niche,? according to the FEIS. It?s found on sandy, open beaches, where its primary habitat is overwash flats at accreting ends of islands and in the sparsely vegetated zone between the high-tide line and the toe of the dune on non-eroding islands.

The species is intolerant of even occasional flooding or overwash and of vegetative competition.

It role in the ecosystem is as an effective sand binder.

The major threats to seabeach amaranth include beach stabilization structures, beach erosion, tidal inundation, ORVs, and pedestrians. Apparently, the plant also has its predators. Such herbivores as deer and rabbits find it tasty.

Seabeach amaranth was listed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as threatened in 1993 because of its vulnerability to human and natural impacts and because it had been eliminated from two-thirds of its historic range.

However, the plant has a real knack for disappearing, reappearing, and even disappearing again.

It is called a ?fugitive annual? or a species adapted to inhabit newly disturbed habitats yearly, whose seeds are viable for long periods of time and can be dispersed long distance by wind and water, allowing it to occupy newly created habitat. Seeds can also accumulate around the plant when it dies, allowing it to continue to occupy a habitat.

The FEIS lists several examples of this ?fugitive? nature. Seabeach amaranth disappeared in New York from Long Island?s barrier beaches for 35 years before new plants were discovered in 1990, 1991, and 1992. The plant was found in New Jersey in 2000 after not being reported in that state since 1913. It was rediscovered in Delaware after a 125-year absence and on Assateague Island after 31 years.

At the seashore, the seabeach amaranth populations have varied greatly since surveys began in 1985.

In 1987, there were 6,883 plants, and in 1988, there were 15, 828 ? the highest in the 25 years of surveys. The next year, 1991, the population dwindled to 3,332 and has been sporadic since then with no plants reported in 1993 and 1994, only one in 1995, and back up to a mere 98 in 1996.

Only one plant was found in 2004, and it was located on Bodie Island Spit. Two were reported in 2005 ? one at Bodie Island Spit and one on Ocracoke.

And no one has reported a seabeach amaranth plant since.

The Park Service notes that the areas at Bodie Island Spit and on Cape Point, where the plant has historically been found, have been continuously protected by summer and winter resource management closures. However, no plants have been found in these areas. And it notes that large portions of the plant?s historical range at Hatteras Inlet Spit, where plants were found in 2001 through 2003, have eroded away.

Under its selected alternative in the FEIS, the Park Service is prepared for a reappearing act by the wily seabeach amaranth.

Alternative F provides for the Park Service to identify before June 1 suitable habitats at points and spits where the plant has been found in the last five years and delineate those areas with symbolic fencing if they are not already located in a resource protection area.

No areas would currently be protected since there have been no plants in the last five years, but the park says it will be ready.

However, when areas with seasonal resource closures are re-opened before the annual August seabeach amaranth survey, they would be checked for any trace of the plant.

Any plants found would be protected by a 30-foot-by-30-foot closure, which might protect them from being crushed by ORVs or stomped by pedestrians, but how will park officials keep away those hungry deer and rabbits?

We can be assured that if a seabeach amaranth pops up on the seashore, it will be one very coddled plant.

And you have got to admire a plant that hangs onto its survival so tenaciously ? coming and going and coming back again.

Actually, the seabeach amaranth deserves more respect.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

To learn more about seabeach amaranth, go to these websites:

http://ecos.fws.gov/speciesProfile/profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=Q2MZ