Shorebird nesting is winding down at Cape Hatteras National Seashore. In fact, it’s over for the federally listed piping plover.

There are no piping plover nests or chicks on the beaches, and there aren’t likely to be any at this point.

The season’s results for the piping plovers are dismal and disappointing. For all the effort that has gone into protecting these tiny shorebirds, only two chicks successfully fledged this summer.

According to the National Park Service, 16 pairs of piping plovers were breeding on the seashore this year — one on Bodie Island, seven on Hatteras, and eight on Ocracoke. That’s close to the number of pairs that have been nesting in the seashore for the last five or six seasons.

However, only two chicks survived to fledge. That’s way below the record year of 2010 with 15 chicks fledged, though slightly better than 2002 and 2004 when there were no fledged piping plovers chicks.

I can’t hazard a guess at how much money goes into protecting these birds on the seashore, especially the federally listed piping plover . In fact, it would probably take the Park Service a good deal of time to figure it out.

However, I think it’s safe to say that those two piping plover chicks are million-dollar babies — or at least close to it.

It’s disappointing for the birds, for park officials, and for the park’s users who surely hope that all these protection efforts result in more birds.

At this point, you begin to wonder if there ever will be — or, more importantly, can be — more birds.

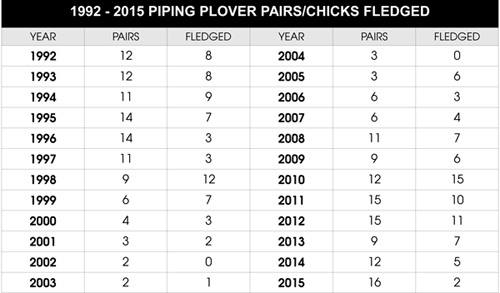

Looking at the chart that accompanies this blog is interesting. It shows the number of piping plover breeding pairs and chicks fledged for the past 24 years.

It is not particularly easy to pick out patterns or trends. The 1990s seemed just okay for fledging, though 1998 had the second highest number of chicks fledged — 12. And those chicks were produced by just nine pairs — fewer than many of the years before and after that.

I wonder what was so special about 1998.

The years 2000-2007 were pretty dismal. Many fewer pairs — two or three — produced many fewer chicks that survived to fledge — zero in two of those years.

The year 2008 seems to start another upward swing — peaking when 12 pairs produced 15 fledged chicks in 2010.

However, it’s been downhill since then.

The Southern Environmental Law Center, and the two environmental groups it represented in a 2007 lawsuit against the Park Service for its lack of an off-road vehicle plan — Defenders of Wildlife and the National Audubon Society — like to take credit for the upswing. The groups claim that the numbers are rising because of increased ORV restrictions.

They claim the upswing is a result of the consent decree that was agreed to by a federal court in the spring of 2008 to settle the lawsuit. Under the terms of the consent decree, ORV regulations and nesting buffers were instituted that are very similar to the ORV plan the Park Service adopted in 2012.

However, what do these groups have to say now that the numbers have been on the way down since that 2010 record of 15 fledged chicks, followed by two years of 10 and then 11?

Although I am not a scientist who studies these things, it seems pretty clear that the one variable that the Park Service really can control in its natural resources management program– human disturbance from pedestrians, ORVs, and pets — is not making the difference it was intended to.

Then, there is the issue of predators. Although chicks are not monitored 24 hours a day, seashore biologists think that most of the chicks are lost to predation.

In recent years, the Park Service has instituted an aggressive predator control program that removed or killed many mammals that feast on the baby birds — feral cats, raccoons, coyotes, otters, foxes, and the like.

But, even as more animals are killed, fewer chicks are surviving to fledge. Now, seashore biologists are looking increasingly to avian predators.

Some long-time beach users point to the changed topography of the island — the loss of vast sand flats that provided an environment that the piping plovers need for foraging for food.

The sand spit at Hatteras Inlet has eroded to about nothing in recent years, and piping plovers no longer nest there. The Park Service has let the sand flats around the Salt Pond at Cape Point become covered with vegetation that completely changes the topography and probably provides cover for predators.

Cape Lookout National Seashore, just to our south, provides a much more piping-plover friendly environment. There is no human habitation on the seashore, it’s accessible only by boat, ferry, or small plane, and, for a variety of reasons, the barrier islands that comprise Cape Lookout have many more wide, sandy and muddy flats and inlets that come and go.

A brief look at Cape Lookout’s piping plover success shows that there are many more pairs that prefer to nest there — as many as 51 in 2012. However, since 2000, there have been as few as 13 — in 2004.

Since there are more pairs, you would expect the birds to produce more chicks that fledge, and they do — 47 in 2013.

However, interestingly, the fledge rate for chicks at Cape Lookout during some seasons has been even more abysmal than at Cape Hatteras.

It’s also interesting to note that the most dismal recent years at Cape Hatteras — 2001 to 2004 — were also the lowest at Cape Lookout.

All of this raises a number of interesting questions.

What are the barriers to more successful nesting at the seashore? And can they be removed?

Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout seashores are at the southern edge of the piping plovers’ breeding range. With sea level rise, are the seashores becoming less suitable for nesting — and will they become even more inhospitable in the future? Is it then worth the protective measures now in place for the birds?

Should seashore biologists continue to struggle to make the seashore more inviting to breeding piping plovers if they are doomed to nesting failure here?

The seashore’s new superintendent David Hallac, whose Park Service career has been in natural resource management, isn’t ready to answer those questions yet.

But they do make him even more excited about the idea of starting a new program of science workshops at the seashore that will be open to the public. The workshops would bring in scientists to review the park’s plan for managing various species of wildlife.

The workshops, he said, “would improve our ability to tease out factors” in the management plan, in addition to human activity, that affect nesting success.”

Hallac said he would like to start the workshops in the coming year, but it might take two years to get the program underway.

CAPE POINT UPDATE

Only one unfledged American oystercatcher chick remains in the way of reopening Cape Point to vehicle and pedestrian access.

The chick will fledge in about 10 days to 2 weeks. However, the ORV management plan calls for keeping the 200 meter buffer in place for another two weeks after the last chick fledges.

It is unclear what seashore officials plan to do. Keeping the buffer in place for the additional two weeks could keep Cape Point closed until almost the end of August.

After the chick fledges, the plan allows the seashore to establish a pedestrian corridor to the Point.

UPCOMING PUBLIC MEETINGS

The Park Service is planning five public meetings over the next two weeks to get public input into the latest round of changes to the seashore’s ORV management plan. The changes were mandated by legislation passed in Congress last December to assure more public access to the seashore.

You can click here to go to an Island Free Press story about the regulations under review, the meetings, and how to comment.

Two of the meetings are in the seashore — at Ocracoke and Buxton — and the others are on the northern beaches at Kitty Hawk, in Raleigh, and in Hampton, Va.

If you want more reasonable public access to the seashore’s beaches, make it a point to attend one of the meetings — or at least find out what’s under review and submit your comments.