As I write this on Friday morning, Aug. 5, Tropical Storm Emily has been downgraded to a wet and windy low pressure system, but weather forecasters are predicting that the storm may re-form into a tropical system in a day or so. If so, they are forecasting that it will pass by Cape Hatteras out in the Atlantic, perhaps fairly far out to sea.

In that case, we might see rough seas and rip currents and maybe some good waves for surfers ? but nothing more.

Of course, the storm is still down around the Bahamas and forecasts for tropical systems can change drastically.

So, for now, all eyes are still on Emily.

And just the fact that there is an Emily out there is a chilling thought for most Hatteras islanders.

Most of us remember Hurricane Emily in 1993. It?s been 18 years, but for those islanders who witnessed the storm?s fury, it may as well have been yesterday.

The storm?s surge from the Pamlico Sound was 10.5 feet in some areas, and most of the southern Hatteras villages ? from Avon to Hatteras ? got 5 feet or so of tide. Rodanthe, Waves, and Salvo, and Ocracoke were mostly spared the storm tides.

Wally DeMaurice, who then led the National Weather Service office in Buxton, which closed not long after the storm, called Emily ?the hurricane of the century? for lower Hatteras Island.

Indeed, not even the oldest residents could remember a storm surge to match Emily?s ? not even in the legendary hurricanes of 1933 or 1944 or the giant storm of 1899. DeMaurice said the water level rise may have been higher than at any time since an 1846 hurricane opened Oregon and Hatteras inlets.

Indeed, not even the oldest residents could remember a storm surge to match Emily?s ? not even in the legendary hurricanes of 1933 or 1944 or the giant storm of 1899. DeMaurice said the water level rise may have been higher than at any time since an 1846 hurricane opened Oregon and Hatteras inlets.

Emily was the first hurricane to threaten the island after I moved here full-time in 1991. And, it really didn?t look like a very impressive storm as it approached the East Coast.

There was a mandatory evacuation. Tourists left, but not most islanders. And on Tuesday, Aug. 31, the day of the storm, my husband, who had ridden out many hurricanes at our house in Brigands? Bay, told me ?not to sweat it.?

Before nightfall, he was regretting those words.

Emily formed south of Bermuda and headed straight west toward Hatteras. However, it was a Category 2 storm and was expected to make a turn to the north before it hit Cape Hatteras.

That turn eventually came ? at the very last minute.

In a 1993 interview, DeMaurice said that he was ?sweating buckshot? as he sat in the Weather Service office in Buxton and watched Emily?s gaping eye move ever closer to Cape HatterasIt finally did make that turn to the north ? just 13 miles off the Cape. By then, it had intensified to a Category 3 storm.

Although Emily would have been much more devastating if the storm had passed over the island and then turned north up the Pamlico Sound, no one who was around on that day has forgotten the storm and won?t anytime soon.

What started out as what old-timers might call a ?really good blow? took a nasty turn.

When the storm turned north right off the Cape, the wind switched to the northwest and picked up, sending an incredible wall of water from the sound over the island, floating vehicles and flooding low-lying houses.

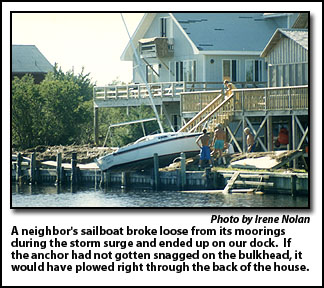

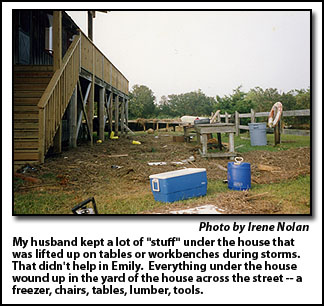

Our house sits on 8-foot pilings, and the tide got to about 5 ? feet under the house. We were an island, totally surrounded by raging tide, topped by 2- or 3-foot waves.

Emily was a slow moving storm, and the southern Hatteras Island villages were in the western eyewall of the hurricane, DeMaurice said, for about 1 ? hours.

During that time, he said, winds were sustained at hurricane force ? 74 mph. The Weather Service recorded a gust of 98 mph just before the wind instruments stopped working about 6 p.m. DeMaurice said the gusts at Diamond Shoals tower, about 14 miles off the Cape, were measured at 142 mph. At other places in Buxton, wind gusts of 107 up to 138 mph were measured.

?However,? DeMaurice said, ?we did not have 138 mph damage. We had 100 mph damage.?

The wind brought down hundreds of pine trees in the Buxton Woods ? just snapped them in half like toothpicks.

But the wind damage paled by comparison to the water damage inflicted by the tidal surge.

Right after the storm, county officials estimated the damage at $12.6 million, which doesn?t sound like a lot until you consider it all happened in about a 20-mile stretch of island from Avon to Hatteras village.

According to officials, 683 primary homes of residents were affected by the hurricane.

That included 168 houses that were destroyed, 216 that were uninhabitable because of major damage, and 144 that were uninhabitable because of minor damage.

About 25 percent of the year-round, single-family houses were destroyed or uninhabitable because of Emily.

And there was more than $3 million in damage just to Cape Hatteras School.

No one was killed or injured in the storm, but the economic damage was devastating.

Not only were island homes damaged, but so were scores of businesses, which meant many folks were out of work.

On top of that, tourists were kept off southern Hatteras for 11 days after the hurricane, adding insult to injury for those businesses that could open up and causing them to miss the busy Labor Day weekend.

There was no water for a day or so, and the power was out up to three and four days. The weather was hot and sticky as we began picking up the pieces.

Massive piles of ruined bedding, furniture, carpeting, appliances, and clothing began to accumulate up and down the highway and on the back roads as the clean-up began.

As always, islanders stuck together and neighbors to the north and south and concerned folks from around the country showed up to help. .

President Clinton declared southern Hatteras a federal disaster area and the Federal Emergency Management Administration set up shop at Cape Hatteras School to help residents apply for low-interest loans.

The interfaith community helped residents for months after the storm.

In the first weeks, help poured in from the American Red Cross, The Salvation Army, and the United Methodist Men. The Red Cross alone ? with 167 workers on the scene ? served 30,000 meals to residents and relief workers during the recovery.

State and federal agencies, as well at the National Guard, helped clean up the damage and haul away debris.

If you know where to look, you can still see some of Emily?s scars, even after 18 years.

The weather folks who get together to name tropical systems have a policy of retiring the names of storm that inflict widespread damage, such as Andrew that devastated South Florida in 1991.

The damage from Emily was not considered serious enough to retire that name.

However, it was plenty serious if you were a southern Hatteras Island resident in 1993.

And that is why some of us still shudder when Emily?s turn comes around again.

We hope this storm slips by unnoticed.