English archaeologist says all ‘lost colonists’ came to Hatteras Island — but did they? By CATHERINE KOZAK

After concluding his most recent dig on Hatteras Island in March, English archaeologist Mark Horton has declared that the Roanoke colonists did not disappear after 1587 — all 100 or so of them went to the chiefdom of Croatoan to live with the friendly Croatan Indians at what is today Buxton.

In claiming to have solved the oldest colonial American mystery – the fate of the so-called “Lost Colony” – Horton, with the University of Bristol, also dismissed years of speculation from other archaeologists and historians who have hypothesized that friendly or not, the Indians could not or would not feed the entire colony.

“Hatteras is an incredibly fertile place,” Horton told an overflow crowd at a March 31 presentation in Hatteras village. “It’s hard to think you’d actually starve here on this island.”

The only clue the colonists left of their possible whereabouts after Gov. John White left for supplies were “Croatoan” and “Cro” carved in a tree and a post.

Of course, Croatoan was here, the archaeologist continued, and he believes that all of the colonists would have traveled the 50 miles down the coast to stay with the Indians.

“Quite clearly, White’s map pointed to it,” Horton said. “It seems wisest to go with simple explanations . . . because this seems to be the most economical solution to the problem.”

Horton says evidence the team has uncovered in Buxton and nearby sites show that Europeans and the Croatan Indians coexisted peacefully for a “long time.”

Horton did not respond to an email seeking clarification of his statements made at the presentation.

But Charles Ewen, director of East Carolina University’s Phelps Archaeology Laboratory, said he remains unconvinced. Not only is it not revelatory that the English and the Croatan had contact, he said, but the findings so far are pretty much more of what has already been found.

“Show me the evidence – and it’s got to be more than a few 16th century artifacts,” Ewen said in a telephone interview. “I would like to see some structures, some evidence of European burials. I would like to see more than a scattering of artifacts that could have gotten there some other way.”

Islanders and numerous academics and historians have long believed that European ancestors of some native Outer Banks families had assimilated with Native Americans, but there has never been proof when or if that happened, or if Outer Bankers descended from the Croatan or other tribes.

Nearly every historian believes that some colonists had gone to Croatoan, but the most frequent conclusion – pieced together from historical records – is that the colonists likely split up, with some traveling inland.

Scott Dawson, president and co-founder of Croatoan Archaeological Society, a group of volunteers mostly from Hatteras Island working with Horton, said in an interview that those assertions are false. He said that the CAS digs show that the colonists assimilated with the Croatan, and had plenty to eat.

“They’re getting murdered on the mainland – why would they go there?” Dawson said of the Roanoke colonists. “I’m just trying to get to the truth – they were well fed and they didn’t split up.”

During his presentation, Horton, an expert in contact archaeology, explained that he was drawn to start exploring Buxton based on the late East Carolina University archaeologist David Phelps’ “remarkable” work at the Cape Creek site in the 1990s.

“He found enough to get us excited,” Horton said.

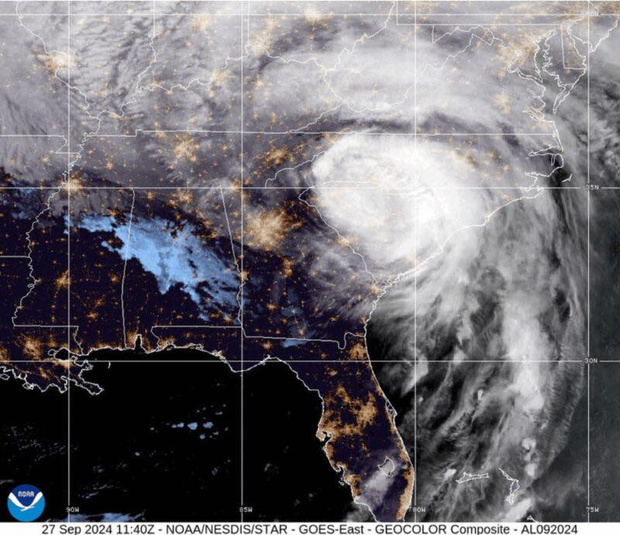

Phelps, who was renowned for his work on early Indian civilization in northeastern North Carolina, started excavating the half-mile site in Buxton Woods in 1993, after Hurricane Emily exposed a huge area of midden, or everyday trash. Over the years, Phelps’ archaeological teams unearthed thousands of artifacts, including three hearths, a 16th century gunlock, copper and brass, and lead droppings from bullets. Those findings, Phelps had said then, indicated for the first time that the English could have lived among the Croatan Indians.

In September 1998, a gold signet ring was unearthed, an electrifying discovery that Phelps initially thought showed clear evidence of a connection between the colonists and the Indians. Although the find stands as one of the most significant of colonial archeology, it was later determined to be in a layer of soil from the 17th century – which means it landed in the dirt when the colonists were long dead.

Unfortunately, Phelps never got around to publishing reports of his findings, and many of the artifacts from his digs remain in boxes at ECU. Horton said he has reviewed Phelps’ field notes, but he found it difficult to make sense of them more than 20 years after Phelps’ work at Cape Creek.

Much of the excavating done by Horton’s team — volunteers with CAS and Bristol University students — has been on the edges of and adjacent to Phelps’ sites.

“This is an extraordinary, remarkable site,” Horton said. “Probably the very richest in North Carolina.”

Since 2009, the team, excavating a total of 75 pits in layers of dirt dating as far back as 10,000 – 8,000 BC to as recent as 1750 has found buckles, dress pins, coin weights dated 1644 and 1648, a rapier, bricks and pieces of brandy bottles. Pieces of waste copper, lead and glass beads – similar to Phelps’ workshop discoveries – indicate there was manufacturing at the site. There were also lots of fish scales and turtle bones, oyster shells, deer bones, bird bones, corn and pea species. So far, there has not been any wheat, an English grain.

A piece of slate is currently being scanned by a new machine at NASA.

The recent find of additional postholes was significant, Horton said. Some of the hundreds of unearthed postholes are square, which could point to English influence.

“We don’t know yet whether they are European or Native American houses, ” Horton said.

Besides Cape Creek, he said there are other significant Indian sites — Hatteras village, by the Hatteras ferry dock, and the top end of Ocracoke village. Indians would have lived along the sound and exploited the resources of the sounds and inlets.

Horton said that the Lost Colony connection is what gets everyone excited about Croatoan, but he said he is as interested in the site’s rich Native American archaeology.

Horton said he is working on a book about the Croatoan digs. A student has written a dissertation about the excavations, but Horton said he has not yet published a report on his findings.

Horton characterized ongoing work by the First Colony Foundation in Bertie County in eastern North Carolina as besides the point. The nonprofit group of professional archaeologists is excavating a site shown on a 16th century map that disputes Horton’s belief that all the colonists went to Croatoan.

“The water was muddied by discovery of an Elizabethan map,” Horton said during his presentation. “This, however, has not deterred another group of archaeologists to go to where the fort was located.”

Dawson also dismissed the group’s work, saying “there’s no science to back up what they’re saying.”

Foundation archaeologist Nick Luccketti, whose resume includes helping to discover Jamestown, said that 16th century Border Ware and other artifacts of daily life found at the site indicates that a group of colonists had stayed there for a period of time. A report on “Site X,” as it’s known, will be released in a few months.

Luccketti said that no one disagrees that 16th century artifacts – typically trade or salvaged items – have been found at Cape Creek, or that some colonists probably went there. But what ultimately matters in archaeology is the context.

“I have not seen any evidence at Croatoan,” he said, “of artifacts that indicate that Englishmen were living there.”