Gauges Added to Improve Flood Prediction

If there is anything to conclude from the recent spate of natural disasters and the coronavirus crisis, it is that data powers action, whether responsive or proactive. Data can illustrate the past, reflect the present and predict the future.

And as Northeastern North Carolina has seen all too clearly, flooding will be much more a feature of its tomorrows than its yesterdays.

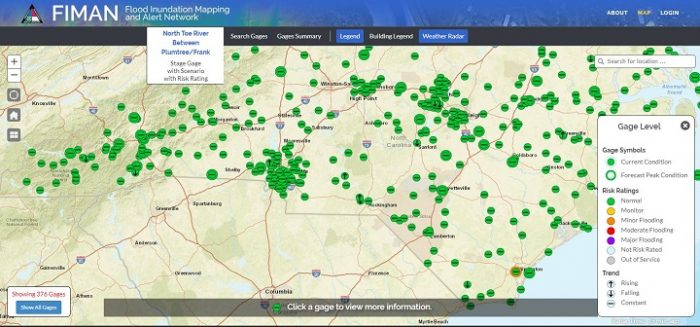

That’s why gauges that measure rainfall and stream elevation installed at hundreds of locations in North Carolina, part of the state Flood Inundation Mapping and Alert Network, or FIMAN, remote monitoring stations, have proven to be remarkably useful tools in flood management and climate science.

Working with North Carolina Emergency Management, the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership recently funded three new gauges to increase real-time and projected knowledge of flooding events in the low-lying northeast region.

“The goal is to prevent the loss of life and property,” said Heather Jennings, APNEP program manager.

Jennings said that the partnership provided a total of $80,000 for the three new stations at Far Creek off U.S. 264 in Engelhard and at Pamlico Sound off secondary road SR 304 in Hoboken, both in Hyde County, and along the Currituck Sound in Mackey Island National Wildlife Refuge in Currituck County. Some of the funds, she added, also went toward solar panel modifications and online software upgrades at other locations.

Upgrades are planned at stations at Rodanthe Harbor, Pungo River, Cedar Island/Pamlico Sound, North Fork of the Alligator River at N.C. 94, Ocracoke Island/Pamlico Sound and Oriental/Neuse River, said Thomas Langan, engineering supervisor in the risk-management section at North Carolina Emergency Management.

The new technology, which includes GOES satellite transmitters, will enable FIMAN to integrate with the National Water Level Observation Network run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, he said.

The Water Level network, which began in the late 19th century, has contributed much to understanding tides and sea level trends.

Each new battery-powered FIMAN station will be equipped with meteorological and cellular transmission technology, a radar water-level sensor, and a solar charging system, all of which jointly collect environmental, hydrological and weather data.

“Water levels in the Albemarle-Pamlico Sound are driven primarily by wind and tidal influx, which results in unpredictable high tides and storm surges during extreme weather events,” according to APNEP. “The impact of these events, including saltwater intrusion of freshwater streams, is expected to increase in occurrence and severity in the future.”

The “FIMAN 1.0” system was launched in the western part of the state shortly after the one-two punch in September 2004 of hurricanes Ivan and Francis, which resulted in major flooding in the mountains, said Langan.

The 2.0 phase incorporates cutting-edge technologies and broadening the system through numerous partnerships including, among others, the state Department of Environmental Quality, the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA, which owns and operates most of the ocean gauges on the coast.

Of FIMAN’s current total of 394 gauges, Langan said, 375 are “risk-rated” at minor, moderate or major levels in conjunction with local emergency managers and weather service field offices. Including public and private partners, data from more than 550 gauges statewide are fed into the system.

Gary Thompson, state Emergency Management’s assistant director for risk management, said that the state has a “gauge build-out plan” that is guided by “where the impacts are” and is somewhat open-ended.

“Our goal is to get more coverage,” he said.

Although FIMAN broadly uses the term “gauge” — the website is phasing out the alternate spelling of “gage” — the network involves far more than a water-level instrument. The website provides real-time data on elevation levels of streams, rivers and other water bodies, as well as rainfall and weather information. Some gauge locations are limited to only providing rain amounts or water elevation stages while others have the capability to monitor weather data.

But the FIMAN website has pulled together the multiple sources of historical and current flood data and provides different ways to understand the risk, including a preengineered and prebuilt “inundation library” tailored to certain elevation and water levels near gauge stations.

Data is transmitted in the west by radio repeaters and in the east by satellite and is shared with the National Weather Service. Each gauge can be located on a map on the FIMAN site and can be clicked on for specific details.

But the beauty of FIMAN is that it is as useful to the general public as it is to public officials.

An especially impressive satellite mapping tool allows a resident to go to the site, zoom into their neighborhood, and calculate how high the predicted flood levels will go on their property. Information is provided on water depth predictions in each building and estimated damages.

After weather and news outlets began recommending the tool, it has become a go-to site for the public during storm season.

“We had over 40 million hits on the FIMAN during Florence,” Thompson said.

Flood-prone Tyrrell County, which has two gauges on the Scuppernong River and one at the intersection of the North Fork bridge and the Alligator River, posts a link to FIMAN on its website that is shared frequently by residents, said Tyrrell County Emergency Management Coordinator Wesley Hopkins.

“Water level is pretty important to them,” Hopkins said.

Tyrrell is barely above sea level and is surrounded and intersected by sounds, rivers and creeks. FIMAN has given the county a valuable source of data in managing stormwater and flooding.

“It helps out a lot,” Hopkins said, including communication with citizens about the risk. “The interactive map you can bring up of the town you live in and the different scenarios — that’s a pretty good educational tool.”

The network also offers an alert function that people can sign up for that provides a text to their phone with customized risk ratings.

According to the February 2018 state hazard mitigation plan, flooding is North Carolina’s most common environmental hazard.

According to the February 2018 state hazard mitigation plan, flooding is North Carolina’s most common environmental hazard.

“Not only does it have many flat and low-lying areas, but it also has lots of coastline in the east and valleys in the western region that are all prone to flooding after heavy rainfall accumulation,” the document said. “Based on historical evidence, it is highly likely (between 66.7 and 100 percent annual probability) that North Carolina will continue to experience flooding events in the future.”

And climate change, the plan said, is expected to increase the risk of impacts from flash flooding and stormwater, especially in the southeastern United States.

Although flooding is not a challenge unique to North Carolina, the state’s expanding and increasingly data-rich flood gauge network is still pretty unique.

“FIMAN is a North Carolina product that we developed in North Carolina,” Thompson said. “But we share what we’re doing. We just had a conference call with Pennsylvania and Iowa (officials.) We also partner with local governments.”