The hunt for original homes on Hatteras and Ocracoke

by Maggie Miles

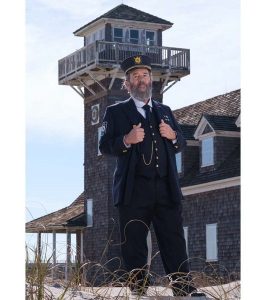

Keeper James Charlet seeks to learn their untold stories

After quitting his job following 25-years as a classroom teacher and relocating his family from Charlotte, NC to Hatteras in the late ’80s, Keeper James Charlet—known then simply as James Charlet—had an epiphany. Despite teaching North Carolina history and even writing a state-adopted textbook on the history of North Carolina for fourth graders, Charlet discovered that there were numerous untold stories of the Outer Banks’ rich history that he wasn’t aware of.

After working in restaurants, fish houses, golf courses, and hardware stores for a few years, Charlet secured a lead interpreter role at Roanoke Island Festival Park right after its opening. And during his daily drives to Manteo, Charlet became captivated by the distinctive architecture of an old building in Rodanthe.

That building turned out to be the Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station, a former station of the United States Life-Saving Service and United States Coast Guard, now serving as a museum dedicated to its history. The more he learned about it, the more amazed he was at this history he had never known. His wife noticed the building too and got a job there. Charlet joined quickly after as they become co-managers of the site.

“Chicamacomico had one really great story, which I knew very well and had told a thousand times. But the more research I did, the more I discovered there were hundreds, probably thousands of stories like it,” Charlet told the Voice. The great story he is referring to is the 1918 Mirlo rescue, which involved saving 42 sailors from the British Tanker that was struck by a torpedo from a German U-boat in World War I.

Charlet decided to dedicate his work to sharing the untold stories. Over the past 30 years, he has done so through various projects, books, articles, speaking engagements, and history tours, assuming his historical persona as Keeper James.

His latest project is no exception. Following the success of their project documenting the history of historic flat tops in Southern Shores, Charlet and the Friends of the Outer Banks History Center (FOBHC) have embarked on a new endeavor to explore, honor, and record the original homes of Hatteras Island and Ocracoke. They are delving into the history of these structures, the families who owned them, floor plans, additions, notable residents and significant events. The only requirements for inclusion are that the structure be at least 100 years old and consist of a minimum of 50% original materials.

Charlet believes that these homes, tucked away on the soundside and concealed from view behind new developments along Highway 12, hold untold stories from history, just like Chicamacomico and the flat tops of Southern Shores.

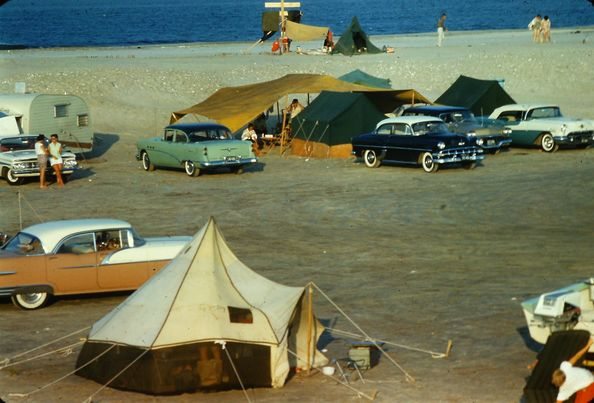

He noted that many of these original homes were passed down by generations and the families that own them have a long history there. Their homes were off the beaten path, and many had private family cemeteries which were very personal. From his discussions with some of the homeowners, he believes many of the homes go back much further than 100 years.

Charlet added that the settlers in that area date back to the middle to late 1700s and came from all over—some looking for a quieter life, some escaping trouble or the law, and maybe even some who were shipwreck victims that decided to stay. He added the foundations of some of the historic homes of Hatteras and Ocracoke are made from shipwreck timber salvaged from the beach.

“I know one in particular that I have seen and have photographs of it myself. I know for a fact that it was made out of a shipwreck, and you’re going to find quite a few of them, even though people don’t really talk about it,” said Charlet.

He also has a few ideas about where the information gathered through this project could lead—citing possibilities such as booklets, rack card maps, plaques for properties to display, homeowners donating original documents and photos to the Outer Banks History Center for exhibition, annual tours of the historic homes, articles in Our State Magazine, and possibly even a PBS NC documentary.

The challenge Charlet faces, however, is finding volunteers, or ‘investigators’ as he calls them, to assist in identifying and documenting the history of these homes, as well as individuals interested in leading the project. FOBHC has already compiled a substantial “starter list” of possible homes, thanks to the assistance of Dawn Taylor and the Hatteras Island Preservation Society, and Charlet has developed a blueprint for completing the project.

At a time when an increasing number of historic homes and buildings are being demolished to make way for newer and larger ones, much to the disappointment of locals who grew up with them, Charlet sees this project as a means to make a positive impact. According to him, historic homes hold the same significance as any historical artifact, but not everyone is taught to recognize their value.

“It signifies a different period, a different time, a different lifestyle, something that still exists, and we’re honoring it because it made it through to now. And, you know, wow, aren’t things different?” he said.

Charlet asserted that while many tourists come to the Outer Banks for the beach, projects like this help people realize that the area is more than just a beach destination. The historic homes and buildings of the Outer Banks possess a rich history, he said. “And I think that would help people realize not only what it is, but also encourage them to pay it more respect.”