Coastal Primer: A closer look atcritical habitat for loggerheads

Fifty years from now the average annual number of loggerhead sea turtle nests should nearly triple on beaches from North Carolina to Georgia.

That’s the projection and a goal the federal government has set in designating critical habitat for loggerheads, a species that has, for decades, been listed on the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

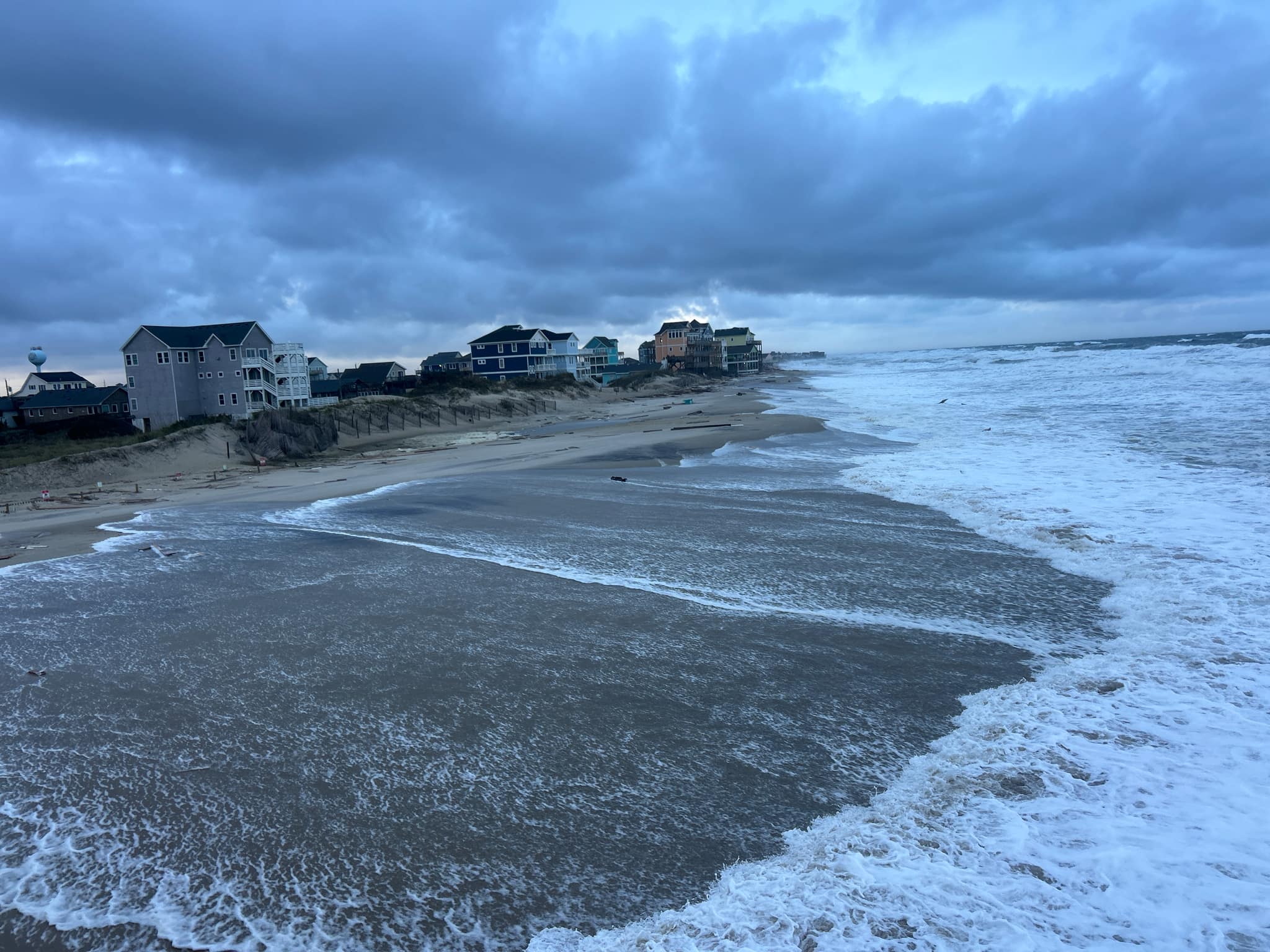

The final rules establishing critical habitat for loggerheads off and on the shores of the Northwest Atlantic Ocean became effective Aug. 11, a date preceded by highly charged debates about how an added layer of protection for sea turtles might negatively affect the economic driving force of North Carolina coastal towns – their beaches.

Most designations of critical habitat have sparked similar fears that the actions would add burdensome regulations and unnecessary costs.

In the decades since the loggerhead was listed in 1978, North Carolina beach towns have collaborated with state and federal efforts to protect sea turtles. Most beach towns have volunteer programs that protect and monitor sea turtle nests in cooperation with the N.C. Sea Turtle Protection Program, established in 1983 and managed by the state Wildlife Resources Commission.

Dredging and beach nourishment projects revolve around sea turtle nesting season. Beach communities have tackled issues relating to artificial lighting and obstructions on the shore, both of which can negatively affect nesting.

All the fretting over designating areas as critical nesting and roaming habitat is hype, according to Pete Benjamin, field supervisor for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Raleigh Ecological Services Field Office.

“We designate critical habitat because the law says we have to,” he said. “We’ve been working with the Army Corps of Engineers and beach communities and developed effective methods over the years so dredging and beach nourishment can go forward without adverse effects on sea turtles. In terms of how we deal with these coastal projects the measures we have in place seem to be effective. There should be no real change that anybody would notice with respect to how these types of projects go forward.”

The requirement to review the effects of human activities on critical habitat applies to only to federally authorized or federally funded projects, such as dredging and beach nourishment projects and Coastal Area Management Act major permit applications.

“Now our correspondence to the Corps of Engineers will include a specific section that discusses specific project-related effects on critical habitat,” Benjamin said. “The corps’ decision document will have to have some language in it that refers to critical habitat. It will probably be no more than a few paragraphs.”

Dennis Klemm, Sea Turtle Recovery coordinator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Southeast Regional Office, expressed similar sentiments.

“With critical habitat the issue comes up only when there’s a federal nexus,” Klemm said. “It’s an addition to the consultation process that already exists. In most cases, potential impacts to the species have already prompted regulation and requirements for protections. There really is not a whole lot of expected restrictions, especially for fishing activities.”

Projected economic cost of enforcing turtle critical habitat is about $150,000 annually. North Carolina’s share would be about $26,000.

Crucial Space

Federal agencies, in this case NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, are by law required to identify and establish critical habitat areas for listed species.

“Generally speaking, with a lot of our endangered species, the act said we had something we had to do to the extent formidable at or about the time the species is listed,” Benjamin said. “For a lot of species we did not do that, mostly because of funding and staffing constraints. We’ve always had to kind of prioritize which actions we were going to move forward on. The loggerhead was the species that never rose to the top of the list until we did the work a few years ago to determine those distinct population segments.”

Loggerheads were listed as a single worldwide, threatened species until September 2011, when the agencies jointly published a final rule revising that listing to nine distinct population segments.

Only two of those segments – the Northwest Atlantic Ocean and the North Pacific Ocean – are within U.S. jurisdiction. Though the segments were established, the agencies “lacked comprehensive data and information necessary” to identify critical habitat for loggerheads, according to information published by NOAA Fisheries.

Fewer than two years after the segments were identified three conservation groups – the Center for Biological Diversity, Oceana and Turtle Island Restoration Networks – pushed the issue by filing a lawsuit against the National Marine Fisheries and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for failing to protect critical habitat areas for loggerheads.

In July, the agencies released their final rulings. The fish and wildlife agency established 685 miles of shore from North Carolina to Mississippi as habitat critical to the survival of sea turtles. The fisheries service designated waters one mile out from those shores expanding protected waters of more than 300,000 square miles in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. The ruling is one of the largest areas of critical habitat designation under the law.

The rule includes 88 nesting beaches in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama and Mississippi.

“These beaches account for 48 percent of an estimated 1,531 miles of coastal beach shoreline used by loggerheads, and about 84 percent of the documented numbers of nests, within these six states,” according the FWS rule.

Critical habitat areas are broken into “recovery units.” Nesting beaches from southern Virginia to the Georgia-Florida state line fall within fish and wildlife’s “northern recovery unit” or NRU.

Nests decline

According to the Recovery Plan for the Northwest Atlantic Population of the Loggerhead Sea Turtle, a 325-page document published by the two federal agencies in December 2008 and a second revision to one published in 1984, nest trends from daily beach surveys “showed a significant decline of 1.3 percent annually since 1983.”

“We did observe what looked like a fairly substantial decline of sea turtle nests on Atlantic coast beaches through the ‘90s and the early 2000s,” Benjamin said. “Those numbers seem to be recovering somewhat. I don’t know that we have definitive information on what was behind that decline.”

In North Carolina, loggerhead sea turtle nests averages have fluctuated. The lowest number of nests were recorded in 2004, when 344 were counted on surveyed beaches. That was down from the 1,140 in 1999, but the count jumped to 832 and 1,103 in 2012. That’s the second-highest count since the state began tracking nests in the mid-1990s, according to wildlife officials.

Annual nest totals for the NRU averaged 5,215 nests from 1989 through 2008.

“There is statistical confidence – 95 percent – that the annual rate of increase over a generation time of 50 years is 2 percent or greater, resulting in a total annual number of nests of 14,000 or greater for this recovery unit,” according to the plan.

For North Carolina, that’s an average of 2,000 nests a year.

To reach these numbers, the recovery plan identifies 208 actions that need to be made, some of which include steps currently taken to protect the turtles and their nests.

The highest threats to loggerhead sea turtles include certain types of fishing gear, legal and illegal harvest, vessel strikes, beach armoring, beach erosion, marine debris ingestion, oil pollution, artificial light pollution, predation by native and exotic species and coastal development.

Many of these threats have been reduced since the loggerhead was listed, Benjamin said.

“The goal for every species is to get it off the endangered species list,” he said. “That’s what we hope to do for this species.”

What Is Critical Habitat?

From the Legal Dictionary

The Endangered Species Act requires that at the same time the decision is made to list a species, the secretary of the interior must develop a recovery plan for the species and, with certain exceptions, designate the “critical habitat” of the species.

Critical habitat consists of “the specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed … on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protection.” Critical habitat must be designated on the basis of the best scientific data available and after taking into consideration the economic effect of the designation. An area may be excluded from designation if the benefits of the exclusion outweigh the benefits of the designation, unless the failure to designate will result in the extinction of the species.

Creating critical habitats almost always leads to conflicts and usually lawsuits. In the most famous fight over critical habitat that made a small fish a household name, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1978 that provisions of the federal Endangered Species Act prohibited the Tennessee Valley Authority from completing the controversial Tellico Dam. The 6–3 decision was a victory for the snail darter, the tiny endangered fish whose spawning area in the Little Tennessee River would be ruined by the impoundment of a lake.

(This story is provided courtesy of Coastal Review Online, the coastal news and features service of the N.C. Coastal Federation. You can read other stories about the North Carolina coast at www.nccoast.org.)