A balancing act along the oceanfront – Interagency Workgroup holds final meeting on threatened beach homes

From OuterBanksVoice.com

The Threatened Oceanfront Structures Interagency Work Group held its third and final meeting as a webinar on Thursday, Oct. 12. The meeting focused on the role government agencies and regulations play when structures on the oceanfront are threatened by a retreating shoreline that often puts a building in the surf zone.

For Dare County Commissioner Danny Couch, who represents Hatteras Island, there was one underlying issue to the meeting.

“What’s driving the boat on this is public safety,” he said. “All three of the entities here local, state, and federal, we’re concerned about making sure that people who are enjoying…the best beaches in the United States…it’s about keeping the public safe.”

According to the Department of Environmental Quality, the workgroup, which was established last year, has a mandate to “identify, research, and recommend policy and/or program improvements to establish more proactive, comprehensive, and predictable strategies for addressing structures at immediate risk of collapse.”

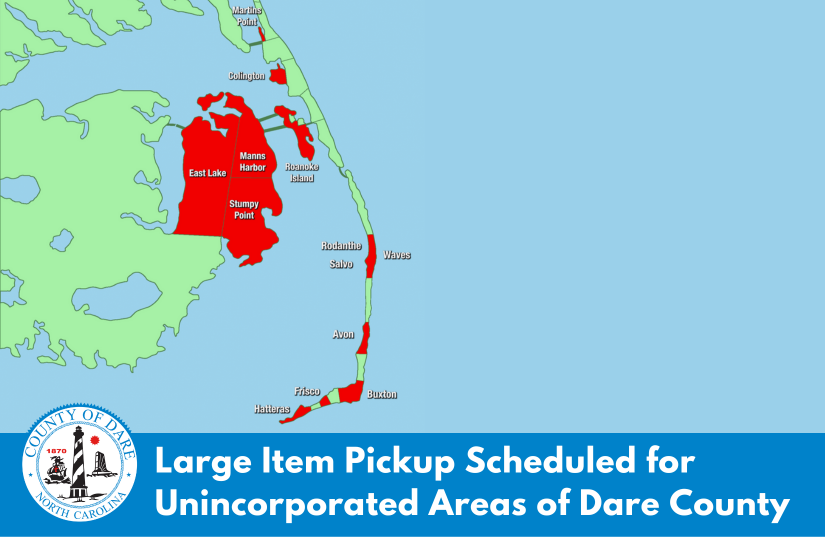

While that mandate covers the state’s entire coastline, some of the Oct. 12 discussion focused on the issues facing threatened homes in Rodanthe. In the past few years, five privately owned oceanfront have collapsed on the beach in Rodanthe, according to a story in the Daily Press—incidents that have attracted national media attention.

The Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CHNS), Superintendent Dave Hallac noted, is dealing with an unanticipated set of circumstances. When homes in Rodanthe were built, they were well back from the foreshore, the dry sand beach that the National Park Service (NPS) owns. Over time, that has changed as the shoreline has retreated.

“This is a very unique area of Cape Hatteras National Seashore, where in northern Rodanthe for two miles, all of the dry sand beach that was owned by the National Park Service for that first two miles has eroded into the Atlantic Ocean,” he said. “In some areas, the pilings of some of a house might find itself inside the boundaries of the Seashore even though it wasn’t located there when it was built.”

Trish Cortelyou-Hamilton, attorney-adviser to the U.S. Department of the Interior, pointed out that there is a provision in the law for the NPS to recover the cost of cleaning up the beach, but there were complicating factors in Rodanthe.

“With respect to the homes that did collapse, the Park Service was not initially in a position to hire a contractor to do that work. And the owners of those rental houses are out-of-state owners, so it’s not as though they could show up and get a contractor in place,” she said.

By the time the contractor was on hand to clean up the debris, Cortelyou-Hamilton noted, the debris field had expanded, but it was no longer clear that all of the debris was from the homes.

“It’s a high energy area…the debris moves everywhere…So we see those people or those owners arguing—prove that debris came from my house,” she explained. “Even though there’s a strict liability cause of action, they have argued that they’re only responsible for their debris.”

Further complicating enforcement is the potential for overlapping jurisdictions. The CHNS eastern boundary is from the low water mark to the first line of dune vegetation and North Carolina claims authority from low tide water line to three miles out to sea. It is possible, noted Division of Coastal Management (DCM) Director Braxton Davis, that an oceanfront property could be under private, federal, and state jurisdictions at the same time.

For oceanfront property owners in Rodanthe, whose homes were originally built well back from the shoreline, their options are limited and expensive. Homes can be moved, and Davis noted that the DCM has a provision that will allow a structure to be moved from the dry sand beach to a location that would not be considered buildable under CAMA regulations because it did not meet setback requirements.

“That does provide us with a little bit of flexibility where we are very limited in land available to move houses back,” he said, but he added that it is “an interim measure” and not a permanent solution.

Hallac cited a pilot mitigation program CHNS has just implemented.

“We…purchased two threatened oceanfront structures in the village Rodanthe,” he said. “This is an exciting project because without other tools in the toolbox right now, it gives us the opportunity to remove the threat to the public and to the resource. It also helps these property owners [who] don’t have a lot of other options. And finally, it allows us to take that piece of property…and turn that into a public access site for the public to enjoy.”

According to Hallac, demolition of the structures should begin within two weeks.

Beach nourishment is also a factor in managing threatened beachfront homes. Nourishment projects are implemented to protect infrastructure—roads and power lines, as an example. A secondary byproduct is protection for oceanfront structures, although, as Hallac pointed out, that protection is often temporary.

“Dare County put a great project into place to nourish the beach in Avon and in Buxton, and a lot of threatened oceanfront structures there were protected incidentally to that project,” he said. “The primary purpose was to protect Highway 12.” But he added, that within a year, the pilings of those structures were “being surrounded by water at certain times.”

Alyson Flynn, Environmental Economist for the North Carolina Coastal Federation, wondered if nourishment projects can be integrated as part of a home relocation program.

“Maybe we look at certain [nourishment] projects as including a stipulation for oceanfront homes…in severely eroded areas like Rodanthe or North Topsail where this is going to give the homeowner an additional buffer for maybe five years. And during that time, the stipulation is that you have to have a plan in place for removal or relocation of your property,” she said.

The meeting highlighted a complex intersection of government regulation, public interest and economic realities, something that Davis, in his opening remarks, described as a balancing act.

“We’re trying to help protect private property, economic development, recreation, tourism, and the environment and all the things that go along with it,” he said. “We want to try to come up with a formula that’s fair, balanced and does the best job of meeting all those competing demands.”

A final report based on the three work group meetings will be issued, Davis said, although he did not specify a date for that.