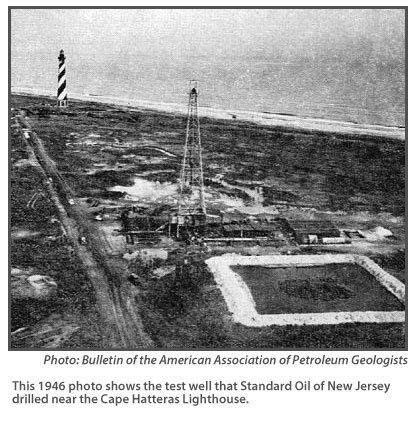

Recent news stories about the beginning of oil and gas exploration off the North Carolina coast reminded me of an article I wrote 15 years ago for another publication.

Most people are surprised to hear that almost 70 years ago, there was an attempt to find oil not only right here on Hatteras Island but in the shadow of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

In 1945, just after the end of World War II, Standard Oil of New Jersey came to Buxton with a great deal of hoopla and publicity to drill a test well, which, at the time, was called “the most important wildcat venture in eastern America.”

On Oct. 2, 1945, in a ceremony that included a number of local people, a Standard Oil official drove a stake into the ground marking the location of what was to become North Carolina Esso No. 1.

The stake was located 1,620 feet southwest of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse at 35 degrees, 16 minutes, and 30 seconds north latitude and 75 degrees, 53 minutes west longitude.

The location of the well was a little more than halfway along the path that the lighthouse traveled in 1999 when it was moved from its old location to a new site 2,900 feet to the southwest to protect it from the encroaching Atlantic Ocean.

On the morning of Dec. 1, 1946, the drilling began on Esso No. 1, a well that Standard Oil officials hoped would produce information about oil deposits along the U.S. East Coast.

On July 9, 1946, the well was “bottomed” in the granite layer of the Continental Shelf at 10,054 feet.

There was no oil. However, according to Standard Oil, the exercise produced a wealth of information about coastal geology.

So, this is the story of North Carolina Esso No. 1 and how it came to be sitting on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in an area that was to become America’s first national seashore and in the shadow of one of American’s most iconic lighthouses.

Most of the information in this blog comes from a Standard Oil of New Jersey publication, “The Story of North Carolina Esso No. 1.”

Before the outbreak of World War II, transport ships delivered oil to most major eastern cities. However, German U-boats patrolling off the Atlantic Coast quickly brought an end to that system. In what was to become known as the Battle of the Atlantic, the U-boats sank oil tankers and other Allied ships with startling regularity in the early months of 1942.

Much of the activity was off the Outer Banks, and the loud explosions, fires burning in the night sky, and black-out curtains became a way of life for Hatteras and Ocracoke islanders.

In the short term, pipelines were built to bring oil to the East Coast. But oil companies were searching for a better long-term solution.

Geologists have long known that sedimentary rock beds of the Cretaceous period occur along the eastern seaboard in a broad band paralleling the coast. With the discovery of oil in the Cretaceous beds off Louisiana and Mississippi, interest increased in the Atlantic Coast as a possible source of crude petroleum.

Early in 1942, spurred by the critical need for oil on the East Coast, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey sent its geologists to study the surface and do detailed research over an area extending from central New York to the coastal area of Georgia.

After the war ended, there was no longer the critical necessity to find oil, but Standard’s search continued on the East Coast, based on the merits of what had been discovered by its scientists during the war years.

The company decided to drill a test well as far east as possible in North Carolina, and Cape Hatteras was deemed to be the most favorable site.

According Standard’s report on the venture, the company did not expect to find oil with the first test well. “It was drilled as the only way to get accurate information as to the nature and thickness of the rocks lying beneath the surface of the earth.”

“Drilling a well at such a location is a difficult and expensive venture,” the report noted. “No improved highways lead to the location. No dock facilities for large ships were available on the ocean side. There was no channel through the Pamlico Sound to any point near the operation. All equipment, special tools and men with the necessary experience would have to be brought from the oil producing states of Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana.”

Standard Oil shipped in the equipment needed, including a 168-foot high derrick capable of drilling three miles into the earth, a huge diesel-electric power plant, and other materials weighing a total of 2.4 million tons. The equipment and materials were shipped by rail to Elizabeth City and traveled by barge down the Pamlico Sound and through a specially dug channel from the deep waters in the sound to a landing dock that was built in Buxton.

The effort was plagued by severe weather. Northeasters, typical of the fall season, drove the barges off course, and, on several occasions, captains had to put into port for safe haven.

In Buxton, the equipment was transported across the soft sand to the well site by Caterpillar tractors pulling flat-bed trailers equipped with Caterpillar treads.

At first, Standard did bring in experienced drilling crews from other states, but these “roughnecks” quickly got homesick on the isolated barrier island. As they left, the company began replacing them with islanders, who, according to the report, displayed “an unusual aptitude for this type of work.”

“They were experienced seamen, ex-Coast Guardsmen, and fishermen,” the report said. “They were good riggers, an essential for a good roughneck. They were physically fit, willing to work and above average in intelligence.”

The late Ray Miller of Buxton worked on the project as a teen-ager.

“I didn’t work on the drilling too long,” he said in a 1995 interview in The Island Breeze. “I was pouring 100-pound bags of mud down a pipe for 12 hours a day. The first day after I started working, I wasn’t sure I could get out of bed.

“They had two shifts with, I guess, about eight men on a shift. They worked around the clock. Twelve-hour shifts. That drill kept a-drilling,” Miller remembered.

While the drilling went on for 24 hours a day for seven months, Esso No. 1 got a lot of attention.

“It is traditional that oil drilling, particularly wildcat drilling, is an operation shrouded in secrecy,” said the Standard Oil report. However, the company had decided that Esso No. 1 would be an “open well” and that complete and accurate information would be available to the public as the drilling went along.

Standard assigned a geologist whose full-time job was to interpret the well to the public. The site was visited not only by public officials and the media, but by scouts and geologists for other oil companies and students and teachers from the geology departments of schools and colleges.

On April 10, 1946, a group headed by North Carolina Gov. R. Gregg Cherry, his official family, and representatives of the media visited the site, where the operations were viewed and samples brought up from the well were interpreted.

The Standard report on the project notes that “because of the importance of this wildcat well and of the unknown character of the sedimentary rocks to be encountered,” the company decided to take core samples of porous sands.

About 25 specially-built boxes of the core samples were given to the state museum in Raleigh “for display as public property.” Samples were also sent to state and federal government agencies, oil companies, universities, and students for their use in their studies.

“Esso No. 1 found no oil,” the Standard Report says. The well cost the company $477,000.

“It was difficult, troublesome, and expensive but well worthwhile. The knowledge gained by this test has confirmed the judgment of Standard’s geologists and justifies further search for oil in northeastern North Carolina.”

Standard Oil went on to drill one more test well in the area — in the Pamlico Sound.

On Oct. 18, 1946, the site for North Carolina Esso No. 2 was located “at a point approximately three miles from the eastern beach of the Pamlico Sound and about thirty-two miles north of the location of the first test well.”

The water there was about 5 feet deep. On a large, specially built submerged barge, the derrick, diesel power plants, pumps, and mud tanks were erected, and around-the-clock drilling on this second wildcat adventure began.

Ray Miller of Buxton went on to work on the boats on Esso No. 2. He said that when the oceanside and soundside mapping was finished about three years later, Standard packed up and left the area. Some of the local men went on with the company at other locations for a while, but Miller decided to go to sea.

Standard said the odds against finding oil at Esso No. 2 were also slim. And, indeed, there was no oil there either.

Also in the report, the company said “that the heart of the petroleum geologist was gladdened by the existence of splendid, thick beds of sandstone that could act as oil reservoirs.”

“Massive beds of very porous sand were encountered at several depths while drilling through formations of the Cretaceous period which indicated that if oil accumulations are found they may be of considerable magnitude.”

When the test well at Cape Hatteras was completed, the hole was pumped full of mud and cement. The cement cap still was visible when work started on the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, and some islanders can still take you right to it.

At the end of the venture, Standard Oil said that the “data taken from the most easterly well in the United States, which have been made available to all for study, will forever be a part of the accumulated scientific knowledge of the world.”

Now, that data will get another look as part of North Carolina’s effort to expand oil and gas exploration

According to a recent article in Coastal Review Online, officials with the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources said earlier this month that samples from Esso No. 1 show enough of a presence of oil to warrant further investigation.

Re-evaluating the well near the lighthouse is part of a larger, statewide assessment by DENR of the potential for oil and natural gas exploration after the N.C. General Assembly passed an energy policy last year.

?What we found is an indication of the presence of oil in that well,? Jamie Kritzer, a DENR spokesman, said in the article. ?Based on that and the technical improvements since 1946, we opted to go ahead and study [the Hatteras] well.?

There are no plans for further exploration at the well site itself, Kritzer said. The original core sample will be analyzed using modern techniques to determine if oil or natural gas exists at the well site, he said. The new analysis could also provide clues to what resources might exist offshore.

When I wrote my article in 1999, I said that North Carolina Esso No. 1 was “an interesting footnote in the history of the island.”

It turns out that could be much more important as the battle over the possibility of drilling for oil and gas off the coast gears up.