If you are going to be on Hatteras Island next weekend and don’t already have plans, I strongly suggest that there is a really cool and fun event that you might want to attend on Saturday morning at 9 a.m.

The event is the dedication of the new Keepers of the Light Amphitheater on the grounds of the Cape Hatteras Light Station in Buxton.

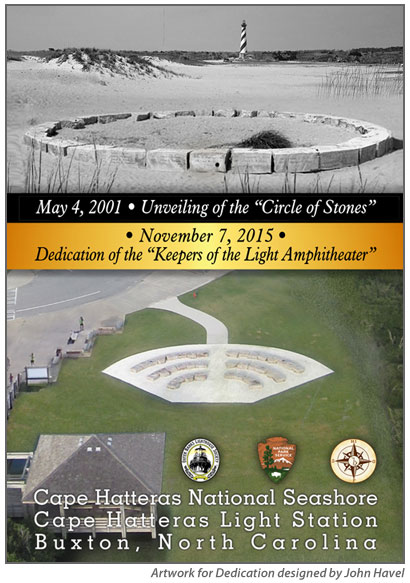

The amphitheater is new, but its seating is not. Many among us will recognize the seating as the large, granite blocks, the so-called “Circle of Stones,” which previously marked the original site of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse on the ocean beach nearby.

The 36 massive stones are carved with the names of the 83 principal and assistant keepers of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse who served at both the present tower, built in 1870, and the tower that preceded it, built in 1803.

The stones, instead of being arranged in a circle, are now laid out in three semi-circles to form the amphitheater seats and they sit in a cleared area covered with crushed stone and shells on the light station grounds.

In future years, they will be the site of various Park Service programs and presentations on the history, culture, and ecology of the lighthouse and its keepers and a place for visitors and admirers to reflect on the impressive structure.

The dedication ceremony is sponsored by the National Park Service, the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society, and the Hatteras Island Genealogical and Preservation Society — three organizations that have been instrumental in deciding the future of the circle of stones.

It’s taken two and a half years to get to the dedication ceremony, but the process that got us here is a real community success story. It’s a “good news” story about the National Park Service and the local community after some years during which the relationship between the two has been anything but cordial.

It’s a story that could have ended quite differently and, we can hope, is another sign that the island community is again moving forward with the Park Service.

To understand what Saturday’s ceremony means, you have to go back to the origin of the Circle of Stones.

In 1999, the National Park Service moved the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse about a half mile to the southwest to protect it from the encroaching Atlantic Ocean.

Moving the lighthouse along a track for that distance was called ?The Move of the Century.? It was an engineering feat of historic proportions and was covered by media from around the world and watched by up to 15,000 lighthouse fans each day during June and July of 1999.

Moving the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse from its historic setting next to the sea was vehemently opposed at the time by some Hatteras islanders, who felt there were other steps that could be taken to stave off the shoreline erosion.

Since then, islanders, even those who were opposed to the move, have accepted it and have gotten used to seeing the tower in its new location in a forest of scrub pine and myrtle bushes.

After the lighthouse was moved, the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society paid almost $12,000 to have original granite stones from the lighthouse foundation ? stones that were cut away to prepare for the move ? engraved with the names and dates of all of the keepers of the Hatteras light.

The huge, heavy granite stones, each weighing 3,000 pounds or more, were arranged in a circle to mark the original location of the historic lighthouse.

The stones were unveiled on May 4, 2001, during a reunion of the descendants of the lightkeepers, sponsored by the lighthouse society, and the Park Service?s re-dedication of the Cape Hatteras Light Station.

Over the years, the circle of stones became a site for tourists to visit and for locals to gather. The circle was the site of many weddings, memorial services, and even some christenings. It was a place of great historic and sentimental significance for both islanders and visitors.

However, as the years passed, the huge stones were tossed around by big waves and covered with sand after several hurricanes and northeasters. This began happening with increasing frequency until finally, after two big storms — Hurricane Irene in 2011, and Super Storm Sandy in 2012 — many stones had sunk below the sand and were barely visible.

After each storm, the Park Service used its heavy equipment to clear away the sand and rearrange the stones.

Finally, in 2013, the Park Service announced that it is no longer practical to keep uncovering and rearranging the stones after each storm.

In a letter to the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society, then seashore superintendent Barclay Trimble asked for the group’s input on two proposed alternatives.

One would be to leave the stones covered and in place, which ?would provide an opportunity to interpret coastal processes.? However, Trimble warned the time will come when the entire circle will be inaccessible for viewing ? presumably because it would be under water.

The other alternative would be transferring the stones to another organization, such as the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras village, which has a Cape Hatteras Lighthouse exhibit, including the original first-order Fresnel lens.

Bett Padgett, who was then president of the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society, replied that the entire board of directors was unanimous in its view that neither alternative is acceptable.

Bruce and Cheryl Roberts, co-founders of the lighthouse society and the folks who were instrumental in getting the stones carved with the names of the keepers, couldn?t have agreed more.

?The Outer Banks Lighthouse Society is not going to stand by and let this happen,? Padgett said in June 2013. However, her group stressed that it did want to work with the Park Service on a solution that would work for all.

Padgett and the lighthouse society board wanted to see the circle of stones kept together and in the vicinity of the Cape Hatteras Light Station, perhaps on the grounds between the current lighthouse location and the double-keepers? quarters.

The Lighthouse Society and the Park Service continued to talk, but they apparently could not get on the same page.

Then the Hatteras Island Genealogical and Preservation Society joined the effort. Many HIGPS members are descendants of lightkeepers, including its then president, Dawn Taylor and current president, Jennifer Farrow Creech.

Taylor posted a change.org petition on her group?s website in late 2013, opposing the Park Service?s plan for the stones. She also sent the petition to U.S. Rep. Walter Jones, R-N.C., in December 2013.

As it turned out, Jones was instrumental in moving along the negotiations between the Park Service and the two preservation groups.

In February 2014, Trimble met with Padgett, Catherine Jordan, director of outreach for Jones? office, and Taylor and Creech at the circle of stones.

As a result of that meeting, the Park Service agreed to load up the stones, move them to storage, and clean and polish them. Also, the Park Service invited the two societies to canvass members and to propose a new location and a design for the stones.

Meanwhile, lighthouse society member Cheryl Roberts found some old e-mails with park officials from about the time of the lighthouse move about the future of the granite stones. In the correspondence, the park committed that “when the time came, it would move the stones closer to the lighthouse and use them as an amphitheater to interpret coastal processes.”

Finally, there was a place for the stones that everyone could agree on — though it took a while to become reality.

Trimble was promoted and left the seashore last summer. He was replaced by David Hallac in January.

In February 2015, a year after the groups met, the cleaned and polished stones were moved to the light station grounds.

And, finally, on Saturday, Nov. 7, the groups involved in finding the happy ending to the saga of the Circle of Stones will come together to celebrate with the community.

The dedication will focus on the history and heritage of the famous lighthouse and its keepers. Both societies will have tables and displays of stories and photos of keepers and their families.

The focus will be on the descendants of the keepers, which as Jenny Creech notes, includes a good number of Hatteras Island natives. There will be supplies available for families to make etchings of the engraved names.

Hallac, Padgett, and Creech will speak briefly. The names of the keepers will be read aloud, followed by the tolling of a bell.

Bett Padgett will sing a song that she has written just for the occasion.

RELATED BLOGS