There has always been a public fascination with the bridge that spans Oregon Inlet.

Hundreds of stories have been written about the new bridge’s construction since the project broke ground on March 8, 2016, and when the county and state celebrated the imminent completion of the replacement bridge via a February “Community Day,” an estimated 1,000-2,000 people showed up to take a stroll on the concrete structure in 30ish degree weather.

But the new bridge certainly isn’t without controversy. Years before the shovels hit the dirt at the 2016 groundbreaking ceremony, lawsuits and debates abounded on whether a 17-mile long bridge or the current 2.8 mile-long structure should be the preferred option, and it took decades of work to clear the massive hurdles and red tape in order to move forward.

And in recent weeks, controversy surrounding the bridge began anew when the suggestion of a new name popped up on the county level, and locals and visitors weighed in on whether to designate the new bridge as the “Marc Basnight” bridge, or to keep the old “Bonner Bridge” moniker.

What’s really interesting, however, is that if you dig deep into the roots of the bridge across Oregon Inlet, it becomes crystal clear that controversy surrounding the bridge is by no means something new.

There were heated debates and arguments, (and yes, massive red tape), years before the bridge was even built, or before the Cape Hatteras National Seashore was officially established.

As mentioned in a previous blog, there’s an interesting and super long chronicle of this history available via a National Park Service publication called “The Creation and Establishment of Cape Hatteras National Seashore,” which is available online here: https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/caha/caha_ah.pdf. It will take you a very long time to read, but with rainy days in the forecast, it’s worth a look if you’re one of the thousands of people who are fascinated with the bridge and its background.

But to weed out a few highlights, a bridge across Oregon Inlet was not always the most popular of ideas, and just like our new bridge, the original Bonner Bridge took years of work before it finally came to fruition.

Let’s start our exploration of bridge controversies by going back in time to the 1930s.

In late November 1934, Roger W. Toll, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park at the time, offered an appraisal of the suitability of the Outer Banks for national park purposes.

Toll concluded that Cape Hatteras is “most suited to development as a national ocean beach” for a handful of attractive reasons. For one thing, he noted, “the area is primitive in character. There are no summer homes nor public resort developments in the area.” As such, he correctly identified at the time that the sheer remoteness of the southern Outer Banks tended to keep land costs low.

Despite this isolation, however, Toll also recognized that the area was reasonably close to large populations, had a good climate, and an abundance of beach recreational opportunities, such as fishing, boating, and swimming. He further recommended the creation of a migratory bird habitat, which a recent Biological Survey was already considering.

In this 1934 assessment, Toll also touched on providing access to Hatteras Island across Oregon Inlet.

Toll suggested that there would likely be an inevitable need for a bridge, but that such a bridge was undesirable in the early stages of park development as it would “destroy the feeling of remoteness.”

Soon after Toll’s input, the National Park Service (NPS) dispatched a party of officials under Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson to confirm the potential of the Outer Banks as a future national park. “In our opinion,” the party reported, “the Cape Hatteras area is decidedly interesting and important enough to justify its inclusion in the National Park system.”

Like Toll, the group also considered a bridge at Oregon Inlet likely, but were also “in favor of preserving the wilderness character of the area by keeping paved roads out, if it is possible to do so.”

This sentiment would come up again and again in the decades that followed – by both officials and politicians studying the feasibility of establishing a National Seashore, as well as by residents on Hatteras Island.

In fact, early meetings and newspaper articles from the 1930s through the 1950s showed that the local population was somewhat split on whether a bridge was needed, with some folks saying that a bridge would provide a lifeline connection to the rest of the world, and others worrying that a bridge and inevitable influx in the population would ruin the character of the deserted and community-oriented island.

Congressman Herbert C. Bonner, who – along with his predecessor Lindsey Warren – pushed for the establishment of a National Seashore, would first bring up the possibility of a bridge across Oregon Inlet in 1949, but he needed more support. The idea of a National Seashore wasn’t always popular with local entities and organizations, and at one point, even the Dare County Chamber of Commerce objected, favoring private development instead.

While the gears turned slowly for the establishment of a National Seashore as well a better access to Hatteras Island, Captain Toby Tillet provided ferry service to Hatteras Island, beginning in 1924. Launching with just a few cars on the back of a barge, Tillet eventually expanded his operations to accommodate up to 14 cars per crossing, and eventually sold his ferry service to the North Carolina Highway Department in 1950, which continued making daily shuttles across the inlet in the years to come.

Keep in mind that at this point, the idea of a bridge had been floated around, but there were no concrete plans in place to move forward with building a connection from Hatteras Island to the rest of the Outer Banks.

But this all changed for two reasons – congestion, and bad press.

Paved roads began to connect the villages in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and in late 1952, a road was completed from Pea Island to the village of Hatteras. Without the threat of getting stuck in the sand, more visitors became interested in accessing the remote island, and started to line up for a ride on the ferry across the inlet, causing heavy congestion on a regular basis.

On May 9, 1954, an op-ed entitled “The Ferry Scramble” by Manteo publicist Aycock Brown was published in the State Magazine. In the piece, Brown criticized the bottlenecks and delays caused by the ferries at the Alligator River and at Croatan Sound, as well as the congestion caused by the ferry at Oregon Inlet.

Brown said that the problem was a continual nuisance for anyone trying to cross Oregon Inlet, and that the state should have fixed the ferry problem before improving the roads.

In 1955, the state asked the current NPS Director, Conrad L. Wirth, to help it obtain a fourth ferry. The justification, according to Assistant Secretary Lewis, was that traffic had increased far beyond expectations due to the expanded activities associated with visitation to the National Seashore area, the operation of the Coast Guard installation located there, the activities of the Fish and Wildlife Service of this Department, the need to keep communications open to the villages on Hatteras Island, and increased activities associated with the national defense in the Cape Hatteras area.

On August 30, 1961, the Park Service issued a press release discussing its support for congressional legislation that would allow the agency to help the state of North Carolina build a bridge across Oregon Inlet. The bill was submitted by Bonner on May 1, 1961, and sent to the whole House on August 28, 1961 (HR 6729).

Per the aforementioned NPS article, the Park Service was interested in helping to pay for the bridge, and essentially reversed its early position, if for no other reason than the congestion generated frequent criticism both by the public and the media.

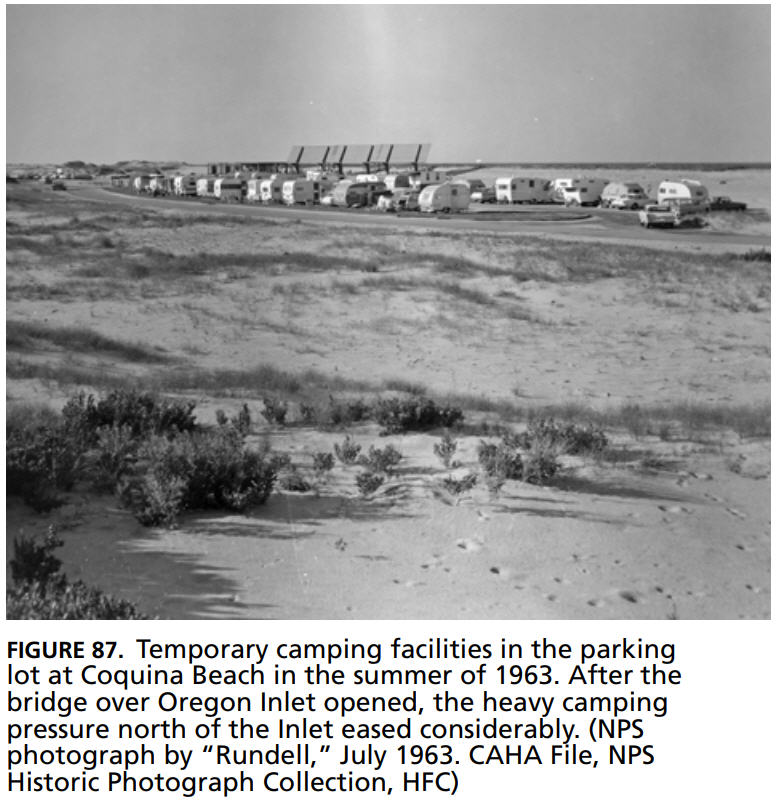

At this time, traffic congestion was so bad to Hatteras Island that a makeshift and temporary camping area was set up in the parking lot at the Coquina Beach Day Use Area to accommodate folks who had to wait overnight for a ride across the inlet.

Even so, as the bill for a new bridge was being debated, there were some concerns about “wilderness preservation” – concerns that would be echoed decades later when the replacement bridge was proposed. Just like our new bridge, there were also concerns about who would foot the hefty bill, as the $2 million price tag rubbed some government officials the wrong way.

The House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee, however, would eventually go on to approve the bill with minor changes, noting that much of the park land was donated or willingly sold by local citizens, (which naturally offset the bridge cost for the U.S. Government), and that the bridge would be maintained by the state, despite being located within a National Park. As a result of these persuasive arguments, the Bonner Bridge was approved for construction on October 11, 1962.

Here’s a fun fact! – Because Bonner was a driving force behind the construction of the bridge, President John F. Kennedy gave Bonner the pen he used in signing the bill as a memento.

After the bill was signed, it took roughly two years for the bridge to be build, and along with the establishment of the National Seashore in 1953, and the paving of roads in the late 40s and 50s, it introduced a brand new era of tourism to Hatteras Island.

Early opponents of the bridge were correct that the Bonner Bridge changed the character of Hatteras Island, but they were also correct when they stated, (30 years before it was built), that a bridge would be inevitable.

Again, this predication of inevitability mirrors our current bridge situation.

Even when a lawsuit was filed in 2013 on behalf of environmental groups who were concerned about the impact to the local and natural environment, everyone seemed to know that a new bridge would have to be built at some point.

With the Bonner Bridge’s lifespan ending in 1993, and alternatives like a revitalized ferry system from Rodanthe to Stumpy Point not remotely feasible to accommodate the population, there was going to be a new bridge of some sort – It was always just a question of when.

After all, consider that rare moment in the past 56 years when islanders didn’t have a bridge, which occurred when a barge struck the Bonner Bridge in 1990 during a storm. For six weeks, the island was once again disconnected from the rest of the Outer Banks, with the only access available via ferry, boat or plane.

Years ago, I remember hearing that when repairs were complete and the bridge was finally open, there were waves of locals on the southern end of the bridge, cheering and greeting the supply trucks that were lined up to access the island once again. My favorite story about the bridge closure of 1990 was that the first truck across the repaired bridge was a Budweiser beer truck, which understandably generated the most enthusiastic response from the crowd. (Unfortunately, I can’t verify that this story is 100% true, but I love the image nonetheless.)

Essentially, a bridge across Oregon Inlet has always generated controversy, and debates may linger years from now, when this historic moment has passed and we’re all just used to crossing the new structure, 90 feet in the air.

But a few generations from now, when the “new” bridge exceeds its lifespan in 2119ish, (and assuming the islands are still around), there’s a solid chance that – based on precedence, anyways – the bridge debates will begin anew.

A better story is Sheila, then Owner with her husband of the Down Under at Rodanthe Pier, was in labor and on the way to Nags Head in labor with her husband. Son was born in the parking lot at South end of bridge

Should have mentioned the birth was when “the ship hit the span” and bridge was out so coul.d not get across. As I recall they arrived just minutes after it was breached.