Back in March, Island Free Press published an FAQ guide to explain the complicated background and current issues that were occurring at Buxton Beach.

Nearly two months later, a lot has changed and there has been a mild increase in progress and a major increase in community involvement.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the Dare County Board of Commissioners will be hosting a public meeting on Tuesday, May 14, at 6:00 p.m. at the Fessenden Center in Buxton.

While there have been public meetings hosted by the National Park Service and the newly formed Buxton Civic Association in the past few weeks, this is the first time that the USACE has presented an in-person opportunity to answer questions from the local community.

With that in mind, here’s an updated and scannable FAQ guide on the problem for newcomers, as well as what has changed in the past several months, and how the public can continue to help.

What’s the problem?

There have been multiple reports of petroleum smells and sheen along a roughly 500-yard stretch of beach at the end of Old Lighthouse Road since two offshore hurricanes – Franklin and Idalia – brushed the Outer Banks in early September 2023.

In addition, the two storms uncovered a new mess of discarded infrastructure, including the foundations of abandoned buildings, pipes, cables and other debris.

As of early May, most of the infrastructure has been covered by sand after consistent mild weather and southerly winds, but during multiple storms in the winter and spring months, the remnants of some of these old structures – and particularly the sprawling foundation of the former Terminal Building – were clearly visible along the shoreline.

Where is this happening?

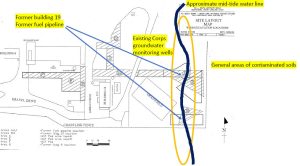

The petroleum smells most often occur on a stretch of shoreline between the end of Old Lighthouse Road and the first, southernmost jetty at Old Lighthouse Beach in Buxton. This is where the abandoned military infrastructure is located as well.

As a result, a three-tenth-of-a-mile section of beach is closed to the public. The rest of the 75-mile Cape Hatteras National Seashore is wide open.

Why is this happening on this small stretch of Buxton shoreline?

The site where there are persistent petroleum smells and old infrastructure on the beach is the former home of a military base.

In 1956, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CHNS) issued a Special Use Permit to the Navy for the construction and operation of Naval Facility Cape Hatteras, based on the condition that the military leave the site exactly as they had found it after they left. That 1956 agreement can be found here.

The Navy base was used for submarine detection during the height of the Cold War from 1956 to 1982, with monitoring activities primarily occurring at the former Terminal Building – a now-oceanfront structure with a cable that extended approximately 13 miles into the Atlantic Ocean.

The U.S. Coast Guard acquired the facility in 1984, and subsequently used the site as a logistical, communication and medical support center for the four Outer Banks-area Coast Guard stations. The Coast Guard used some of the facility buildings until around 2005, but a large percentage of the overall military site was no longer in use by the early to mid-2000s. The Coast Guard completely left the site in 2010.

The infrastructure that is visible on the beach today is the remnants of these former military operations, and primarily the Navy base, although some of the leftover wastewater facilities are linked to the Coast Guard as they used these amenities as well.

Why is this happening now?

Prior to September 2023, these issues were literally buried.

Here is a little background info on the roots of the problem, which Island Free Press published way back in February 2024.

Hurricane Franklin was a long-lasting storm that formed on August 20, 2023 and dissipated on September 9. Idalia was a powerful Category 3 when it made landfall in Florida on August 30, but had weakened to a tropical storm by the time it skirted the Outer Banks.

Both storms remained well offshore, but caused significant erosion to the Buxton Beach site, exposing structures and other contaminants that had previously been hidden under the surface.

On September 1, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CHNS) closed a stretch of shoreline between the end of Old Lighthouse Road and the first jetty at Old Lighthouse Beach due to this erosion-driven exposure of old infrastructure from the former Naval Facility at Cape Hatteras.

On September 25, Dare County and North Carolina officials issued a precautionary advisory due to impacts from petroleum-contaminated soils, which were also exposed by the recent beach erosion event.

“The Department of Defense (DoD) is committed to protecting human health and the environment and improving public safety by cleaning up environmental contamination of former military properties,” stated a September 25 press release from the USACE. “If it is determined the petroleum-contaminated soil is related to a Formerly Used Defense Site (FUDS), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers does respond to DoD-generated contamination that occurred before the property was transferred to private owners or to federal, state, tribal, or local government entities.”

In late October, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Savannah District announced that they were working with partner agencies – namely the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ) – on investigative efforts to determine “any necessary corrective actions” under the umbrella of the FUDS program.

Then the winter arrived, with a barrage of typical winter storms, and the issues became progressively worse with each new wave of erosion.

Two days after a coastal storm impacted the Outer Banks in early February, local surfers reported an unusual sheen on the waters at Old Lighthouse Beach, and they came out of the ocean reeking of fuel.

“I believe the only reason we could actually see the amount of [fuel] on the water was because the ocean was completely calm and glassy, with no surface chop from wind,” said famed local surfer Brett Barley in a February interview. “It became very apparent how much more severe this situation was than previously thought back in the fall, and from what you can observe from the land.

“I came home and my wife could smell the diesel on me, even after scrubbing my face with soap and showering.”

When a late March storm hit the Buxton Beach area a month later, the full scope of the debris under the surface was momentarily visible, which included the former Terminal Building foundation, a mess of septic pipes and cables, and other infrastructure like the base of a former communications tower.

As of early May, much of this infrastructure has been covered up by shallow layers of sand, as Hatteras Island has enjoyed a multiple-week period of mild weather and southerly winds. However, some cables and debris still stick out of the sandy beach, which is one of many reasons why this small area of shoreline remains closed to the public.

Where are the petroleum smells and sheens coming from?

One likely source is a steel pipe that is 1-3 inches in diameter and is close to the recently exposed Terminal Building foundation.

National Park Service (NPS) personnel initially noticed that the steel pipe was emitting petroleum smells over the winter and spring months, after several storms.

“Based on odors coming out of the pipe and the sampling, there may be some type of petroleum there,” said National Parks of Eastern North Carolina Superintendent, David Hallac, in an earlier interview.

But it is highly possible there are additional sources of petroleum as well, based on other observations from NPS personnel who have patrolled the Buxton shoreline on a regular basis since the problems first surfaced in September 2023.

For example, NPS personnel and beachgoers have also reported finding clumps of peat that smell like fuel in the past few months along the shoreline, and these likely stem from former marshes and other sites that are further away from the oceanfront.

“On many occasions, we would find peat sediment, and multiple pieces of that sediment clearly smelled as if they had some sort of petroleum contamination,” said Hallac. “Most of these samples came back positive for petroleum contamination – and this included portions of sand, not just peat.”

How often does the petroleum smell occur?

“Approximately half the times we were there, we would smell an odor,” said Hallac in a March interview, referring to regular site visits by NPS staff, who also kept a logbook of when the petroleum smell was noticeable.

However, the smell seems to come and go based on variable conditions.

It appears to be most noticeable during storms, during extreme high tides, and when sand and sediment are carved out of the adjacent dunes from substantial wave action – a process that’s known as vertical erosion.

Who is responsible for remediating/cleaning the beach?

The consensus by stakeholders is that there are two agencies – the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Coast Guard – who are responsible for cleaning up the site.

This is because of the original 1956 special use permit that said the site would be returned to its pristine condition after military activities concluded.

The two agencies are responsible for different aspects of the massive remediation efforts, however.

The persistent petroleum smells and petroleum-contaminated soils (PCS) fall under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ FUDS program, however, there is some debate and confusion as to what agency can address the remaining infrastructure and debris on the beach. (More on that later.)

“The [FUDS] Program addresses environmental liabilities that resulted from Department of Defense activities at eligible properties,” stated Cheri Pritchard, Media Relations Chief for the USACE Savannah District in an email to Island Free Press on Feb. 12. “To be eligible, the property must have been under the control of the Department of Defense prior to and transferred out of the Department of Defense control by Oct. 17, 1986.”

But a corresponding and separate issue of pesticides and PCBs, (which are manmade organic chemicals consisting of carbon, hydrogen and chlorine atoms), is likely linked to the U.S. Coast Guard, as these problems were present at the site when the Coast Guard completely left the facilities around 2010.

Why weren’t these issues addressed before?

They were, but not completely, which is why issues have surfaced since the September 2023 storms.

In 1998, the Army Corps of Engineers approved the Buxton Beach area as a FUDS site and began acting in response to petroleum contamination in several areas.

The USACE demolished a number of structures and both above-ground and below-ground storage tanks that were not being used by the Coast Guard, including the former Driftwood Club and the Terminal Building which were removed in the 1980s under the Navy’s Special Use Permit. Evidently, not all of these structural elements were completely removed from the shoreline when the demolition occurred.

Groundwater monitoring and bioremediation by the USACE have been routine in the years that followed, due to detections of petroleum hydrocarbon contamination that exceeded NCDEQ standards.

Meanwhile, the Coast Guard removed a good chunk of the structures that they had used during their years of operation, including 16 buildings, a tennis court, a softball field, a swimming pool, a sewage treatment plant, two steam boilers, two diesel generators and a TV tower.

In 2010, a report conducted by the Coast Guard found that wastewater facilities on the site had semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOC), metals, pesticides and PCB compounds present in the surrounding soil at concentrations above EPA standards. And while the Coast Guard removed some of the wastewater facilities in 2012 that they had used, they did not remove or remediate the two drain fields that were supposed to be addressed.

“For decades, they have been performing remediation activities,” said Hallac in an earlier interview, referring to the USACE and the Coast Guard. “It seems like more work is necessary to complete the job.”

What has changed in the past two months?

First, let’s start with where we were just two months ago.

Back in February 2024, after the USACE conducted a months-long investigation, there were no plans to take action at the site because the USACE was unable to find any clear source of petroleum.

Here’s an excerpt from one of our first in-depth stories on the issue, posted on February 19, 2024:

“We’re just simply asking that the organizations that used the site prior to departing, which were the Navy, (and this would be the Army Corps of Engineers on behalf of the Navy because they are responsible for Formerly Used Defense Sites), or the Coast Guard, (who also used the site), remove either hazardous materials and other materials consistent with the original agreements, to leave the site essentially the way they found it,” stated [David] Hallac.

At this time, however, there is no action planned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ (USACE) FUDS Program to address the problems.

While the FUDS program seems like the most viable and logical option for remediation and clean-up operations, recent USACE investigations have discovered that, (under the rules of the program), FUDS funds and efforts do not apply to Buxton Beach.

“We (USACE) have conducted subsurface investigations at various locations on the beach and have not found a source of petroleum,” stated Cheri Pritchard, Media Relations Chief for USACE Savannah District in an email to the Island Free Press on Feb. 12, 2024. “Unfortunately, in the absence of a source, the FUDS program cannot take any action at the site… FUDS needs to confirm there is a source associated with Navy activity at the site for this matter to fall within the scope of the FUDS Program.”

In essence, although petroleum has been found in the area, in the absence of a source – or a confirmed location as to where the petroleum originated – action can’t be taken at Buxton Beach using FUDS funding, because it’s not 100% certain where the fuel is coming from, per the program’s rules.

Here’s where we are now.

Remember that exposed pipe that NPS personnel said had a noticeable fuel smell? It is about to be removed by the USACE, which is a huge step forward in just seven weeks.

On Friday, May 3, the USACE awarded a $525,000 contract to SLSCO, LTD for work at the former Naval Facility in Buxton, as well as corresponding soil sampling and testing work.

“In addition to the contract for the pipe getting awarded and engaging in more communication, a research team from the Environmental and Munitions Center of Expertise is currently doing a deep dive into the site, researching archived facility and real estate records, prior removal and remediation actions undertaken at the site, maps and other information provided to the Army Corps of Engineers that are associated with the site,” stated the USACE in a May 3 press release.

However, while the pipe and anything attached to said pipe will be removed, the FUDS program cannot address the rest of the infrastructure.

“We have reoccurring meetings with our regional, federal partners such as the National Park Service and the Coast Guard,” said Col. Matthew McCulley, South Atlantic Division deputy commander, in the May 3 press release. “We will coordinate with our higher headquarters and our regional federal partners to determine if there are any existing programs that can be used to remove this infrastructure.”

So why can the exposed pipe be removed under the FUDS program, but not any of the other abandoned infrastructure on the beach?

Here is the explanation of the distinction from the USACE, sent to Island Free Press on May 13:

“Regarding the remnant Navy infrastructure, the FUDS Program can only demolish and remove buildings and structures that were unsafe at the time the property was transferred out of [the] Department of Defense’s control. The structures associated with the remnant Navy infrastructure were not in unsafe conditions at the time the property was transferred back to the National Park Service in 1982, therefore the infrastructure is not eligible under the FUDS Program.

In the News Release Dated May 3, Col Ron Sturgeon said, ‘I acknowledge concerns over removing the remaining infrastructure. However, this activity is not authorized under the FUDS Program because it’s not considered an environmental hazard associated with contamination left behind by a former DoD activity.’

Investigation of the pipe that contains a petroleum odor and associated soil sampling falls under the FUDS Program because these efforts are intended to determine if the pipe was part of a petroleum distribution system, which could be a potential source of petroleum contamination.

As for the sporadic waves of peat balls that smell like petroleum, here is the USACE’s response:

“Currently, the source of the contaminated organic material that has periodically washed up on the shore is unknown. The Corps Savannah District has diligently investigated the beach to find a potential source by sending teams in September, October, November, December, and February to collect soil samples, perform borings, dig test pits, and take air samples. The District’s work is undergoing internal review by another team of experts to determine what, if any, additional investigative steps might be needed.”

Keep in mind that in the May 3 press release, the USACE stated that they were coordinating with “higher headquarters and our regional federal partners to determine if there are any existing programs that can be used to remove this infrastructure.” So, there is still ample hope and possible options when it comes to fully remediating Buxton Beach.

What has changed in terms of community and outside support in the past two months?

In a word, tons.

The Dare County Board of Commissioners, the Outer Banks Chamber of Commerce, the NCDEQ, the Southern Environmental Law Center, the North Carolina Coastal Federation, and various legislators have joined the conversation and demanded an immediate solution for Buxton Beach.

A new Buxton Civic Association has been formed, a letter-writing campaign has garnered support from thousands of residents and vacationers, and the CHNS has launched a new webpage on the issue, and has hosted two public meetings.

Arguably, and at least in the past few weeks, the Buxton Civic Association and the Dare County Board of Commissioners (BOC) have had the most visibility on the issue, and for different but corresponding reasons.

The BOC traveled to Washington, D.C. in April and also met with the USACE in early May to bring attention to the issue and to foster action.

“I can’t help but feel like the trip that myself, Vice Chairman Overman, Commissioner Couch, and the County Manager [Bobby Outten] made to D.C. concerning the petroleum issue in Buxton, that we made some progress,” said Chairman Woodard at the May 7 BOC meeting, referring to an April trip where the commissioners met with Senator Thom Tillis’ staff.

“Superintendent Hallac had been working with [the USACE] for almost eight months and not getting much response out of that group, and so I feel like just three weeks ago, in this short period of time, that we did make some progress meeting with our legislators in D.C.”

The formation of the Buxton Civic Association is also a milestone in its own right.

Following an energized public meeting hosted by the NPS on March 27, a local advocacy group was formed to take action on Buxton Beach, and since then, the brand new Buxton Civic Association (BCA) has made waves through multiple and simultaneous initiatives.

Since the Buxton Civic Association hosted its own first public meeting on April 10, the organization has launched an online petition, built a Facebook page and website, and has been in constant communication with both stakeholders and resources who can help.

The BCA has been communicating with Mike McIntyre, attorney and former United States Representative, as well as other organizations including the National Park Service, the North Carolina Coastal Federation, and the Southern Environmental Law Center. The organization also attended and sponsored the North Carolina Beach, Inlet & Waterway Association meeting on May 9-10 in Emerald Isle – the first Hatteras Island organization to do so – in order to further explore and discuss the Buxton Beach issue.

The BCA is also engaged with the USACE to form an official Restoration Advisory Board (RAB). According to a USACE 1998 Procedures Manual, as well as a 2007 Handbook from the U.S. Secretary of Defense, the purpose of a RAB is to create a line of communication between local communities and the agencies responsible for cleaning up sites that were previously used by the Department of Defense (DoD).

“That, in theory, should be a great conduit where a community group has the ability to interface with the Army Corps of Engineers about this defense site, one-on-one, and ask questions,” said CHNS Superintendent Hallac in an earlier interview.

And if we’re doling out pats on the back for organizations that have been instrumental in moving Buxton Beach action forward, the NPS can’t be overlooked.

David Hallac and his team have spent thousands and thousands of hours on this issue for months. They have been constantly working behind the scenes to get the ball moving for action, while taking the bulk of public blowback through community meetings and close-to-home interactions.

These problems aren’t the National Park Service’s fault, but these problems are happening on their turf, and they have been fighting for a Buxton Beach solution since day one.

Can the public visit Buxton, and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore in general?

Absolutely, yes.

Keep in mind that just three-tenths of a mile of the shoreline is closed, out of 75 miles of Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

There have been recent rumors that the ocean is brimming with oil slicks, or the shoreline is about to be closed from Avon to Buxton. None of this is true. The community is just being loud and outspoken and proactive so that a 500-yard problem doesn’t become an island-wide problem at some undetermined date in the future.

What’s next, and what can the public do to help?

As mentioned, a meeting will be co-hosted by the USACE and the Dare County Board of Commissioners on Tuesday at 6:00 p.m. at the Fessenden Center in Buxton, and the BCA summed up the importance of this meeting best in a May 10 social media update:

“Pack the House,” stated the BCA. “We have been working along with the Commissioners to make this meeting happen. We need everyone to be there and show how much support and passion this community has!”

If you can’t make it, then here is a collection of additional info that the Island Free Press publishes at the end of many of our Buxton-centric articles:

For more information on Buxton Beach, and how to get involved

- The Buxton Civic Association, which was formed as a community initiative to respond to the Buxton Beach issue, meets the first Thursday of every month at the old Buxton Volunteer Fire Department building beside Burrus Field. The next meeting is June 6 at 6:00 p.m. and the public is welcome and encouraged to attend.

- Developing info from the Buxton Civic Association (BCA) can be accessed via the organization’s new website at Buxtoncivic.com or through the BCA’s official Facebook page.

- The public can also join the ongoing email and letter-writing campaign, which was launched in mid-March by Buxton community members.

- Visitors who encounter a fuel smell or fuel sheens while visiting the Buxton shoreline near Old Lighthouse Road should call the National Response Center at 1-800-424-8802 to report the encounter. Include the date, time, location, and basic details of what was seen or smelled, and do not call if you have not experienced the issue first-hand, or have not been physically affected.

Anything else I should know?

Yes. First of all, it bears repeating that while there has been tons of coverage on Buxton Beach, by Island Free Press and many of our outstanding Outer Banks media outlets, only 500 yards of a 75-mile-long National Seashore is affected and closed.

Also, every single person Island Free Press has interviewed in the past two months regarding Buxton Beach believes the end-game goal is not pointing fingers, but fostering cooperation. This remains true, and Tuesday’s meeting with the USACE is an opportunity to keep the collaboration and the conversation going.

“Everyone can work together to try and get some things moving here,” said Hatteras Island Commissioner Danny Couch in an earlier interview. “There are no bad guys here… There’s just a job to do, and all of the ingredients are there to come up with a solution.”

After the Army Corps removes the oil pipe and the source of the oil, a solution for the rest of the problem could be to rebuild the jetties (they could be environmentally natural rock), let the sand come back to cover all the structures that have been covered for decades and allow the jetties to bring back the beach we have all known for decades and decades for a much cheaper price … cost of a couple of jetties that haven’t completely left yet anyway ….. good idea? it’s not mine but I am posting it.