Concern is rising about drastic beach erosion in south Avon….WITH VIDEO

Video by Orville Scarborough

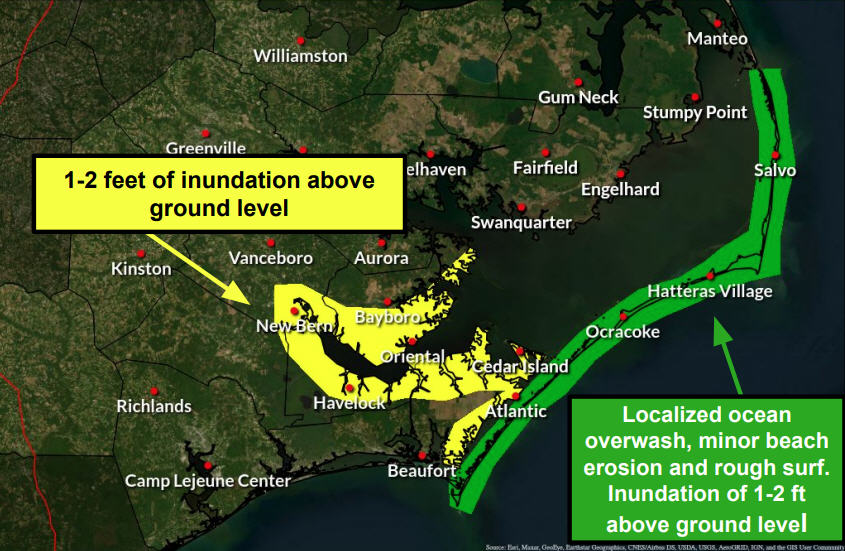

Photos and videos of the Kinnakeet Shores area beach in Avon – a stretch of shoreline that extends from the Avon Pier south to roughly Ramp 38 – have been circulating on social media as startling erosion has surfaced in the past days and weeks.

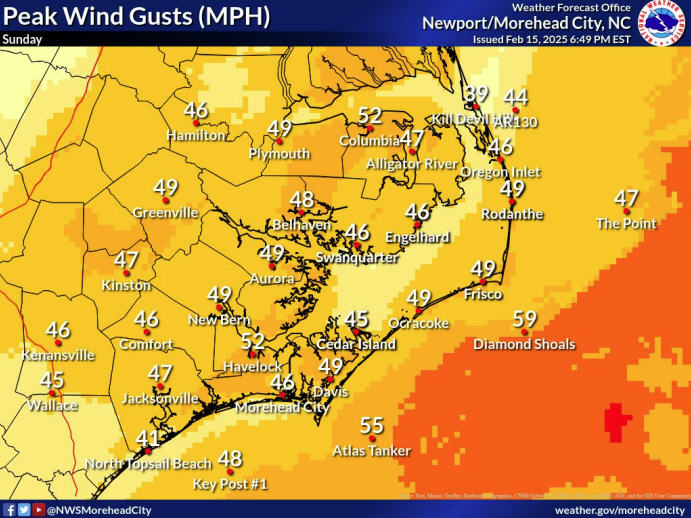

While seasonal erosion is nothing new in the wintertime, the severity of the erosion in an area that once had a double dune line is what is grabbing people’s attention. Off-road-vehicles that are cruising through Avon often have to stop and turn around at high tide, when the route is blocked by breaking waves, and at least one community walkway along Ocean View Drive has been marked with yellow caution tape, as the stairs to the beach now lead to a combination of steep sand walls and nowhere.

“My understanding is that it’s not uncommon to have some beach erosion in the wintertime, and not uncommon for the beach to build back up when winds shift,” says Cape Hatteras National Seashore Park Superintendent David Hallac. “What I hear from local residents, however, is that the erosion that we are seeing this year [in Avon] exceeds what we’ve been seeing in the past few decades.”

Beach-goers who visit the region now will notice an almost sea wall or bulkhead-like tower of sand that’s abruptly cut off by crashing waves during a high tide. As a result, some stretches of the beach have just a few feet of shoreline or less, depending on the winds and tide, before a beach-goer is either forced into the ocean, or literally hits a wall. The problems are well illustrated in the accompanying video that Orville Scarborough shot on a ride down the beach.

Pat Weston, the manager-president of the Kinnakeet Shores Homeowners Association for the past 16 years, has been monitoring the issue since it first began, and says the current problems initially started around the time of Hurricane Matthew’s arrival.

“What we have here now is a result of Hurricane Matthew,” she says. “During Matthew, we had a 225-foot breach in the dunes, and we did have ocean overwash that went across Highway 12 near the post office, but which at the time was an isolated incident.”

That initial incident was quickly addressed, thanks to fast action from the involved parties.

“We were fortunate enough to work with the Park Service, and solve the problem. We got immediate permission from the Park Service to push the sand back from the west to form a berm, and to uncover our walkway,” says Weston. “The Park Service allowed us to do that with cooperation and permitting from CAMA. We were able to do that right away, and that did help.”

The problem now is arguably what should, and can, be done next.

Weston has been researching solutions for troubled shorelines like Avon for weeks. She has meticulously reviewed virtually every possibility – from creating an artificial reef or “wave break” like what exists in the Chesapeake area, to rebuilding the dunes that were originally constructed roughly 80 years ago by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC.)

And some of her findings on how to best address the Avon situation are somewhat surprising.

“I decided to do research on dunes – rebuilding dunes, what the problems are, and why [these problems exist],” she says. “And over the [few] weeks, I found out quite a bit.”

“Dunes can cause erosion, and having dunes is not always a good idea,” she says. “When there is resistance, [like a high sand dune], the wave will become more violent and turbulent, and will take away more sand. The ocean will continue to do that until it removes the obstacle, or the sand dune. Once it’s allowed to overwash, it will re-deposit the sand.”

That seems to be what is happening to the casual observer checking out the central Avon shoreline, as the waves constantly hit the sand wall before retreating back to the ocean. But there are certainly problems with allowing nature to run its course.

“It’s pretty well known that dunes built on the Outer Banks are important right now,” says Hallac “They do protect homes and prevent roads from being washed out.”

“However, on the island, we have gotten rid of washover that would allow for the distribution of sand,” he adds. “The sharp, steep dune can act as a bit of a sea wall that forces the energy downward, and which speeds up erosion. Gentle sloping dunes, however, have a constant redistribution of sand. They allow the island to migrate one way or the other. But when you have fixed structures like homes and roads, [that need to be protected], that’s no longer possible.”

Several homeowners have already been affected by the shortened shoreline, and the immediate short solution for owners who are dealing with encroaching erosion is to talk to CAMA first.

“[Our] recommendation would be to talk to CAMA,” says Hallac. “From a regulatory perspective, they can offer advice to homeowners. It’s certainly challenging when all the beach erodes right to the back of a property, and the CAMA state agency that can provide ‘technical support.’”

Owners will also be relieved to know that if immediate replenishing of sand is needed, at least one recent example has shown that it can be a quick process. Weston had worked with one homeowner earlier in the week to address the damage to their oceanfront home that had occurred over the course of a few days, at most.

“We had both been in contact with the Park Service, and they were very willing to do what was necessary for the homeowner to protect their property,” says Weston. “The owner was able to get permits to bring in sand if he desired, and if he deemed it necessary.”

“We understand the importance of folks protecting their property, and certainly we’ll work with anybody to assess the situation, and rebuild [the sand] on their private property,” says Hallac.

As for long term solutions, Pat Weston and a number of other locals, owners and other involved entities are already discussing the prospect of beach nourishment.

“I’ve always been a proponent of dune building, and now I’m seeing that if we can start a movement for a longer-term solution of beach nourishment to widen our beaches, and give the forces of nature [a chance] to overwash and deposit sand instead of eroding, then we can save years [of erosion] in the future. We’re going to have to make a plan.”

Weston and several other parties are already in the early stages of forming a Beach Committee to discuss options and find out what to do next.

“Nothing happens quickly when it comes to beach nourishment,” she says, “especially when it comes to Cape Hatteras National Seashore. We need to go through NPS, CAMA, and other entities. It just needs to be all coordinated, and everyone needs to join in the same dance so that it can be addressed as quickly as possible.”

“I would say we’re open to having a discussion about beach nourishment,” says Hallac. “We did work with Dare County on a beach nourishment project in Buxton, and we will discuss other areas as well, and plan to do so with the county.”

Granted, there are many areas of Hatteras Island that experience post-hurricane and/or wintertime erosion. Areas in between Frisco and Hatteras, in the northern part of the island, and even on Ocracoke Island have caused attention and notice from both the Park Service and the locals who frequent the beaches.

But the drastic and dramatic landscape of the Avon Beach has really grabbed the attention of everyone who lives in, loves, or is just familiar with Hatteras Island. And while the spring winds and weather shifts may result in some relief, at the moment, it’s an issue that’s at the forefront of everyone’s minds… and everyone’s Facebook feed.

“I think I speak for everybody – island residents and the homeowners association – when I say that it’s very important that we preserve the beach. Our whole island economy is based on tourism. If we don’t have the beaches, they are not going to come,” says Weston.

“The Hatteras Island tourism is very important to the Dare County economy,” she adds. “We all need to stick together and work for the good of the entire island – not just Avon, but all of us.”