Exposed infrastructure and a sporadic but persistent fuel smell have been reported at the popular Buxton Beach, but there is not an immediate solution in the works to address these environmental issues.

Two days after a nor’easter impacted the Outer Banks in early February, local surfer Brett Barley headed to Old Lighthouse Beach in Buxton to take advantage of the post-storm waves.

There were concerns that a strong fuel smell would resurface, as it had in the same general location for months, but Barley and other surfers decided to take the risk, entering the ocean at the southernmost jetty.

“On the paddle out, we realized this was probably a horrible idea,” said Barley. “Upon getting into the lineup, we realized the entire surface of the water was covered in diesel. Not like a huge slick, but every few inches, there were tiny dispersed areas of diesel. You could see it everywhere by the jetty outside the waves.”

As the tide went out and the wind switched in the afternoon, the smell and noticeable slick disappeared, but evidence of the fuel remained.

“I believe the only reason we could actually see the amount of [fuel] on the water was because the ocean was completely calm and glassy, with no surface chop from wind,” said Barley. “It became very apparent how much more severe this situation was than previously thought back in the fall, and from what you can observe from the land… I came home and my wife could smell the diesel on me, even after scrubbing my face with soap and showering.”

This recent incident highlights an issue that has been technically ongoing for decades, but which has accelerated since two offshore storms – Hurricane Franklin and Tropical Storm Idalia – brushed the Outer Banks in late August and September 2023.

In addition to the sporadic but prevalent fuel smells, the shoreline adjacent to Old Lighthouse Beach has visible remnants of multiple structures, cables, and other pieces of uncovered infrastructure from a former military base. Unsafe for the public, this former Best Beach in America honoree has been closed for nearly six months.

Now, multiple federal, state and local organizations are very aware of these crisis-level environmental issues, but many questions remain as to how the problem will be addressed, and who will do the heavy lifting.

The history of Buxton Beach

Prior to becoming a famed surfing and swimming beach, the U.S. Navy utilized the approximately 50-acre site at the end of Old Lighthouse Road in Buxton as a submarine monitoring station from 1956 to 1982, per a lease agreement with the Cape Hatteras National Seashore. The U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) acquired the facility in 1986 and subsequently used the site as a logistical, communication and medical support center for the four Outer Banks-area USCG stations.

Buxton native and Dare County Commissioner Danny Couch remembers the active Navy base well, including the on-site fuel facilities. “Around 1970, the fuel tanks were close to where the ocean was,” he said.

“I was only around 10 at the time, but spills were a regular occurrence, even with the filling up of multiple vehicles. One time I witnessed, easily, gallons and gallons of fuel just gushing out from an unattended vehicle. The spills onto the ground were epic around that time.”

The undersea surveillance system at the Buxton Naval Facility was decommissioned by 1982, and while the USCG used some of the facility buildings until 2005, a large percentage of the military site was no longer in use by the 21st century.

In the 1990s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) began to address some of the problems that arose from having an abandoned military base within a national seashore.

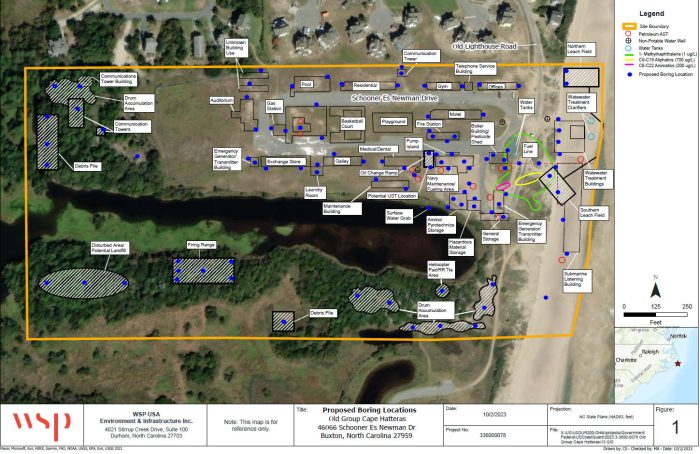

Based on reports from the USACE, seven above-ground storage tanks (ASTs) and 27 underground storage tanks (USTs), were removed from the site in the 1990s. A pipeline discovered between an AST and a former oceanfront structure was later removed in 2000.

Soon after, several groundwater sampling events occurred to support further investigation at the site, and subsequent oil removal in multiple areas followed, along with the removal of an old oil change ramp in 2005.

This background was outlined in a December 2023 report from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ FUDS program, which is often a lead agency when it comes to cleaning up former military sites that are no longer in use.

“The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Formerly Used Defense Sites (FUDS) Program addresses environmental liabilities that resulted from Department of Defense activities at eligible properties,” stated Cheri Pritchard, Media Relations Chief for USACE Savannah District in an email to Island Free Press on Feb. 12, 2024. “To be eligible, the property must have been under the control of the Department of Defense prior to and transferred out of the Department of Defense control by Oct. 17, 1986.”

Beginning in November 2005, multiple groundwater sampling events were conducted over the years as part of the USACE’s “Remedial Action, Compliance Monitoring, and Long Term Monitoring Events.” Results were initially mixed, but starting in 2020, multiple monitoring wells at the Buxton site showed no contaminant concentrations above the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality’s (NCDEQ’s) Groundwater Standards.

By the late 2010s, this stretch of Buxton Beach had become very popular with visitors. So much so, that the speed limit on Old Lighthouse Road was changed from 35 mph to 25 mph, and a new Buxton Day Use Area opened in 2019, with parking for up to 50 vehicles. A second phase for the public beach was also planned, with permanent restrooms and marked parking spaces to accommodate the influx of surfers and beachgoers that were flocking to this busy beach destination.

The southern section of beach that the new Buxton Day Use Area connects with is now closed to the public.

What has changed in the past six months

Hurricane Franklin was a long-lasting storm that formed on August 20, 2023, and dissipated on September 9. Idalia was a powerful Category 3 when it made landfall in Florida on August 30, but had weakened to a tropical storm by the time it skirted the Outer Banks.

Both storms remained well offshore, but caused significant erosion to the Buxton Beach site, exposing structures and other contaminants that had previously been hidden under the surface.

On September 1, the Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CHNS) closed a stretch of shoreline between 46285 Old Lighthouse Road and the first jetty at Old Lighthouse Beach due to this erosion-driven exposure of old infrastructure from the former military facility at Cape Hatteras.

On September 25, Dare County and North Carolina officials issued a precautionary advisory due to impacts from petroleum-contaminated soils, which were also exposed by the recent beach erosion event.

“The Department of Defense (DoD) is committed to protecting human health and the environment and improving public safety by cleaning up environmental contamination of former military properties,” stated a September 25 press release issued by the USACE. “If it is determined the petroleum-contaminated soil is related to a Formerly Used Defense Site (FUDS), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers does respond to DoD-generated contamination that occurred before the property was transferred to private owners or to federal, state, tribal, or local government entities.”

In late October, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Savannah District announced that they were working with partner agencies – namely the NCDEQ – on investigative efforts to determine “any necessary corrective actions” under the umbrella of the FUDS program.

Since this initial wave of Idalia and Franklin advisories and updates, there has been regular monitoring and investigations behind the scenes by the USACE, the U.S. Coast Guard and the National Park Service (NPS).

Often, these investigations crop up as the result of a report of fuel smells issued to the National Response Center, which is the designated federal point of contact for reporting all oil, chemical, radiological, biological and etiological discharges into the environment.

“We are regularly visiting the site to keep track of signs of petroleum contamination,” said National Parks of Eastern North Carolina Superintendent David Hallac. “So, there have been odors, and we’ve also been finding chunks of peat sediment – which is organic sediment from where a historic marsh used to be – that appears to be washing out onto the beach, and a proportion of those peat sediments are clearly contaminated with petroleum.”

The NPS has also noticed the newly exposed infrastructure on these visits to Buxton Beach.

One of these exposed structures is the remnants of Building 19, or the Terminal Building, a structure that originally had a cable that allowed for submarine detection in the 1960s. There are also visible pieces of Building 40, which was a social club known locally as the “Driftwood Club.”

“There also appears to be an incredible amount of additional infrastructure, whether they were utility lines, septic drain lines, or what-have-you,” said Hallac. “We believe some of the pipes that we’re seeing now were lines that may have been coming from above-ground or below-ground storage tanks for the purpose of heating buildings.

“It was our understanding that when the Navy departed, the Army Corps of Engineers – the agency responsible for restoring and remediating Formerly Used Defense Sites – would remove all of the infrastructure that the Coast Guard did not want to use,” said Hallac. “That includes Building 19 and the [other exposed infrastructure] that’s now on the beach.”

What is happening now

There are multiple state and federal agencies that are connected in some way to the accelerating issues at Buxton Beach.

These entities include, (but are not necessarily limited to), the Coast Guard, the Corps of Engineers, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the NCDEQ, and the National Park Service.

Often, when a report of a fuel smell is made to the National Response Center, it flows through multiple channels.

“We have been getting reports, and briefed our investigators who are monitoring,” said USCG Petty Officer Gonzales Biez, noting that when it comes to remediation efforts, “our investigators told us that other government agencies are taking care of it.”

“DEQ’s Division of Waste Management has reviewed plans for this site from the U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and is awaiting sampling results after the completion of that work,” stated Patricia Smith of NCDEQ. “The Department of Defense is still involved, to DEQ’s knowledge, but DEQ is not the lead agency on remediation efforts.”

“We (R4’s Emergency Response Program) and U.S. Coast Guard have received the National Response Center reports concerning petroleum odor complaints,” stated Melba Furlow of the EPA, who noted that the EPA would not be the lead agency when it came to facilitating a response.

Per previous press releases, investigations, historical remediation efforts and general hierarchy when these situations arise, the loose consensus is that fixing the issues is best tackled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ FUDS program.

This is because the problems that are occurring now are likely due to the 26-year existence and operation of the Buxton Naval Facility before it was transferred to the U.S. Coast Guard, and the FUDS Program addresses environmental liabilities that resulted from Department of Defense activities prior to Oct. 17, 1986.

“We’re just simply asking that the organizations that used the site prior to departing, which were the Navy, (and this would be the Army Corps of Engineers on behalf of the Navy because they are responsible for formerly-used defense sites), or the Coast Guard, who also used the site, remove either hazardous materials and other materials consistent with the original agreements, to leave the site essentially the way they found it,” stated Hallac.

At this time, however, there is no action planned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to address the problems.

While the FUDS program seems like the most viable and logical option for remediation and clean-up operations, recent USACE investigations have discovered that under the rules of the program, FUDS funds and efforts do not apply to Buxton Beach.

“We (USACE) have conducted subsurface investigations at various locations on the beach and have not found a source of petroleum,” stated Pritchard. “Unfortunately, in the absence of a source, the FUDS program cannot take any action at the site… USACE FUDS needs to confirm there is a source associated with Navy activity at the site for this matter to fall within the scope of the FUDS Program.”

In essence, although petroleum has been found in the area, in the absence of a source – or a confirmed location as to where the petroleum originated – action can’t be taken at Buxton Beach using FUDS funding, because it’s not 100% certain where the fuel is coming from, per the program’s rules.

There are also no active plans to remove the exposed infrastructure that’s currently visible on the shoreline. Structures that were removed in the 1990s were definitely done so by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, but per the USACE, these previous efforts were not orchestrated under the FUDS umbrella.

“The [FUDS] program can only address issues that were a hazard at the time the property was transferred out of Department of Defense control,” stated Pritchard. “Unsafe conditions arising after Department of Defense jurisdiction are not eligible for FUDS action.”

A full report that summarizes the USACE’s findings, after a lengthy investigation, is expected around the end of February.

Outside of the FUDS program, there are other agencies that could potentially take the reins of remediation initiatives, but there have been no announcements of imminent clean-up efforts by any organization or government entity as of early 2024.

What’s next

Danny Couch is drafting a resolution for the Dare County Board of Commissioners to create a united local government front that will hopefully bring more attention and action to the issue.

“The objective is to show that it has the attention of Dare County officials,” said Couch. “Then, we want to work together with state and federal authorities to rectify the damage and make the area user friendly.

“I’ve been contacted about this for months now, but it’s getting to a point where it’s not going away,” he added. “This is a serious situation that has been passed over, but it’s starting to get momentum now.

“This is people’s health, and it’s happening in one of the top surfing spots in the United States. It’s too blatantly obvious a problem, and too blatantly a public concern to be ignored forever.”

A formal Dare County response is a minor step, but combined with public attention, it might help to propel a solution.

Social media has also been flooded with posts and pictures of the issue, and this notoriety will likely increase as the summer arrives.

The Buxton shoreline between 46285 Old Lighthouse Road and the first jetty will remain closed indefinitely until the current environmental issues are fixed, which makes the new-in-2019 Buxton Beach Day Use Area – a site created because of this beach’s popularity – completely useless.

Frequent visitors to the area are reporting an increase in instances of a fuel smell, and if the February account by Barley and other surfers is any indication, the petroleum problem is getting worse.

So, when thousands of visitors arrive in the summer and discover that one of the most popular beaches in Buxton remains closed, or when waves of people encounter an oil slick while taking a dip in the ocean, then maybe the issue will receive national attention. Until then, a growing chorus of local voices may be the first step to facilitating a solution.

“Everyone can work together to try and get some things moving here,” said Couch. “This has huge public safety implications and there’s just too many variables to ignore. We need to encourage the entities that have to deal with this situation to come up with a plan of action, because ‘it’s not in our wheelhouse’ is not going to cut it.

“There are no bad guys here. Communication has been open and transparent and cooperative. [There is] nothing to suggest any kind of cover-up. There’s just a job to do, and all of the ingredients are there to come up with a solution.”

Buxton Beach on February 14, 2024. Video from Sam Walker.