Expert warns that it’s water – not wind – to watch out for in hurricanes

Jamie Rhome, the man who oversees the National Hurricane Center’s Storm Surge Unit and is blazing a trail with new forecasting methods, told a Hatteras Island audience during a weekend presentation on hurricane preparedness that it’s not the category of a storm that the public needs to pay attention to during hurricane watches and warnings – it’s the storm surge probabilities and predictions.

Rhome is one of the country’s leading experts on storm surge, and he gave a presentation to about 50 people at the Fessenden Center in Buxton on Saturday morning, May 21. On Friday morning, he spoke to county and municipal officials involved in emergency management and gave another public presentation at a Nags Head open house on Friday evening.

The meetings were a public outreach event to get valuable information out on storm preparedness, as well as familiarize the crowd with new research and tracking methods that are being introduced by NOAA’s National Hurricane Center and the National Weather Service.

“We want you to be prepared – that’s why these meetings are being held,” said Board of Commissions Chairmen Bob Woodard at the May 16 meeting.

And there was a singular theme throughout the two-hour morning presentation, which grabbed everyone’s attention.

“If you don’t take away anything else – if you want to go to sleep for the rest of the morning – remember this,” said Rhome. “The Saffir-Simpson scale is not the weapon of choice to determine your vulnerability… It’s storm surge that does the damage.”

The Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale is what most folks follow in the days and hours before a storm makes landfall. Dividing storms into categories based on wind speeds affects whether the majority of people leave or stay during a hurricane evacuation.

For example, most islanders have an internal rule to head west if a category 3 or 4 is expected, but will stick around for a category 1 or a tropical storm.

But, surprisingly, the category has little if any bearing on how bad a storm is actually going to be, according to Rhome. “There is no such thing as ‘just a tropical storm,’” he said.

And paying attention to the category and wind speeds to determine how to react to a storm is a common misguided practice. Rhome reported that 84 percent of people believe that they need to evacuate based on the strength and category of a hurricane.

“That is false – the reason why most people need to evacuate is because of storm surge,” he said. In fact, Rhome said, storm surge causes more than 50 percent of fatalities and the majority of financial loss during hurricanes occurs from storm surge.

And through video clips and images of recent storms, Rhome provided some pretty vivid evidence to back up this central message. The attendees watched before-and-after shots of areas that were devastated by category 1 hurricanes and even tropical storms that made landfall miles away from ruined areas.

A photo of a typical home in Biloxi, Miss., was shown before a hurricane and in a post-storm surge shot where only the front yard tree remained on the property. An aerial view of New Jersey after Hurricane Sandy – which didn’t even make regional landfall as a hurricane – was an equally powerful example of the damage storm surge can do.

“Hurricane Sandy was barely a Category 1 and it cost $65 billion dollars in damage,” Rhome said, “It’s a great example of why category doesn’t matter.”

And as locals who lived through 2003’s Hurricane Isabel will attest, the “wall of water” that marks a storm surge is a force of nature that can’t possibly be combated or controlled.

“Think of it as a bulldozer that just marched and marched and marched,” said Rhome while explaining the effect of storm surge via a photo of a ravaged Gulf Coast shoreline. “… and when it left, everything in its wake was gone.”

The other key point during the presentation was that history plays no role in determining the effect of future hurricanes.

He used the example of the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011 as a prime example on how relying on history to determine future occurrences can go terribly wrong.

When the Japanese nuclear power plant was established in the late 1960s and 1970s, engineers looked back at more than a century of tsunami and storm events to determine how high the water had risen in the past. Once they determined that maximum line of how far the water had risen, they built the power plant just past it.

In March 2011, a tsunami that was triggered by the Tōhoku earthquake went well past that line and destroyed the plant. It was the largest nuclear disaster since Chernobyl in 1986, and was the second disaster to be given the Level 7 event classification on the International Nuclear Event Scale.

“My job is to find the worst case scenario, and once we find it, give it to emergency planning,” explained Rhome. “We call it the ‘Black Swan’ – If I find the black swan, I say ‘Don’t put a power plant here.’

“And the storm you had 10, 20, or 30 years ago will not tell you what the next storm will look like,” he added.

So how is the severity of a storm determined? There are a number of factors that affect storm surge, which don’t include history, but which do make the forecasting of the actual effects of a hurricane easier to determine.

These factors include forward speed, the angle of approach, the shape of the coastline, the slope of the coastline, and the central pressure and / or size of the eyewall. “Just because a storm weakens from a category 4 to a category 1 doesn’t mean you dodged a bullet,” said Rhome. “All of that energy has to go somewhere.”

With this new wave of information, Rhome and his team are able to create Probabilistic Storm Surge reports. “We go in and built multiple tracks and landfall locations, and say ‘If it comes in like this, you’re in trouble,” said Rhome.

“We’re empowering [Emergency Management teams] with much better technology than in the past. So if Drew [Pearson, the Dare County Emergency Management Director] tells you it’s time to go, he’s using the best possible information I can give him.”

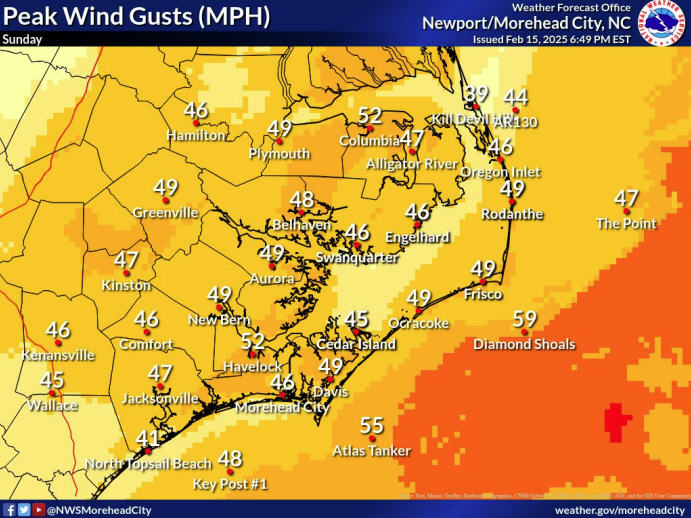

Rhome’s presentation concluded with new information that’s now available on the NOAA website. Subsequent presentations by Richard Bandy and David Glenn of the National Weather Service Office in Newport/Morehead City – Hatteras and Ocracoke Island’s local station – expanded on this new available data.

The prototype of the storm surge forecasts were launched during 2014’s Hurricane Arthur and will be available online for all future storms. Found alongside the other tracking information, maps, graphs, and reports on the NOAA / NHC website for each individual hurricane, these new graphs will highlight storm surge probability and will be posted with the first hurricane watch for a specific storm.

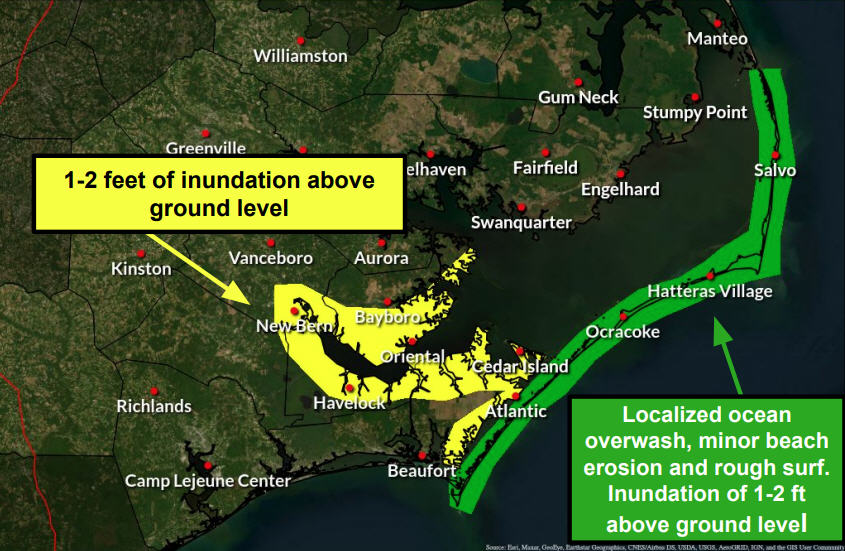

The color-coded graphs show the storm surge probability for each specific region, as well as the potential of how high waters could rise above ground level in increments of three feet — such as 0-3 feet., 3-6 feet., 6-9 feet., and 9-plus feet). Though still being tweaked, the new graphs are a powerful tool for determining a course of action for coastal communities.

And Rhome noted that in future hurricanes, we won’t have just hurricane watches and warning about the hurricanes wind strength, but also storm surge watches and warnings, which may urge evacuations based on the storm surge forecast only.

“They’ve given us the best information in the world to make a determination,” concluded Drew Pearson at the end of the presentations. “Storm surge is not a new phenomenon – but forecasting is.”

And Richard Bandy of NOAA noted that there were some improvements and future developments that are still in the works, including using the technology to forecast the storm surges of winter storms – a recurring and more common threat for islanders – as well as factoring in wave height and strength.

“The probable [total feet of] storm surge does not include the height and strength of waves on top of that,” he cautioned.

It was also noted that this information was being shared with regional and national media outlets. “One of my top guys has gone to the Weather Channel [as a forecaster],” said Rhome. “We’re trying to move the Weather Channel and other media towards storm surge.”

And perhaps the biggest takeaway for presentation attendees? Don’t keep this information to yourself – share it as much as possible.

“Go home, talk to your neighbors, give them a hand-out, and share this information,” said Pearson. “We need to get the word out.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Jamie Rhome — along with Richard Bandy, meteorologist in charge of the National Weather Service office in Newport/Morehead City, and Drew Pearson, Dare County director of Emergency Management — also recorded a Radio Hatteras program for the interview show, “To the Point,” hosted by Island Free Press editor Irene Nolan. The interview will be broadcast on Radio Hatteras at 5 p.m. on two Sundays — June 5 and 12. If you are on Hatteras, you can listen at 101.5 FM or 99.9 FM. Or you can listen to live streaming on the website, www.radiohatteras.org.